LES SENS: par Bertall

[Frontispiece

“How admirable and beautiful are eating and drinking, and what a great invention the human digestive system is! How much better to be a man than an alligator! The alligator can fast for a year and a half, whereas five hours’ abstinence will set an edge on the most pampered human appetite. Nature has advanced a little since Mesozoic times. I feel certain that there are whole South Seas of discovery yet to be made in the art and science of eating and drinking.”

John Davidson

THE

GREEDY BOOK

A GASTRONOMICAL ANTHOLOGY

BY

FRANK SCHLOESSER

AUTHOR OF

“THE CULT OF THE CHAFING DISH”

LONDON

GAY AND BIRD

12 & 13 HENRIETTA STREET, STRAND

1906

All rights reserved

To

THE IDEAL WAITER

They also serve who only stand and wait

Milton’s Sonnet “On his Blindness”

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Cooks and Cookery | 1 |

| II. | Byways of Gastronomy | 20 |

| III. | The Poet in the Kitchen | 41 |

| IV. | The Salad in Literature | 62 |

| V. | Mrs. Glasse and her Hare | 81 |

| VI. | Menus | 112 |

| VII. | Oysters | 166 |

| VIII. | Waiters and Snails | 189 |

| IX. | Dishes of History | 220 |

| X. | Lenten Fare | 242 |

| Les Sens | Frontispiece | |

| Les Aliments | To face page | 30 |

| Les Audiences d’un Gourmand | ” | 89 |

| Les Rêves d’un Gourmand | ” | 135 |

| Des Magens Vertheidigung der edlen Austern | ” | 178 |

| Les Boissons | ” | 194 |

My thanks are due to the Editors of the St. James’s Gazette, the Evening Standard, the Academy, the Daily Mail, the Daily Express, the Globe, the Tribune, and Vanity Fair for permission to reproduce certain portions of these papers.

[Pg 1]

“In short the world is but a Ragou, or a large dish of Varieties, prepared by inevitable Fate to treat and regale Death with.”

‘Miscellanies: or a Variety of Notion and Thought.’ By H. W. (Gent.) [Henry Waring] 1708.

The only thing that can be said against eating is that it takes away one’s appetite. True, there is a French proverb to the contrary, but that really only applies to the hors d’œuvre and the soup. We all eat three meals a day, some four, and a few even five, if one may reckon afternoon tea as a meal. Yet the art of eating—that is to say, how to eat, what to eat, and when[Pg 2] to eat it—is studiously neglected by those who deem they have souls superior to the daily stoking of the human engine.

Whosoever simply wants to eat certainly does not require to know how to cook. But whosoever desires to criticize a dinner and the dishes that compose it—and enjoyment without judgment is unsatisfactory—need not be a cook, but must understand what cooking implies; he must have grasped the spirit of the art of cookery.

Cooks themselves almost always judge a dinner too partially, and from the wrong point of view; they are, almost without exception, obstinately of the opinion that everything they cook must taste equally good to everybody. This is obviously absurd (but so like a cook), for allowance must be made for the personal equation. Nothing tastes so good as what one eats oneself, so it is not to be expected that one and the same dish will please even the most fastidious octette. Still there have been occasional instances.

The late Sir Henry Thompson once had a new cook, and, in an interview with her[Pg 3] after the first dinner-party, she expressed herself as being delighted that everything had been so satisfactory. “But how do you know it was?” asked Sir Henry. “I’ve not given you my opinion yet.” “No, Sir Henry,” said the cook, “but I know it was all right, because none of the salt-cellars were touched.”

It is a mistaken idea that a man-cook can be a cordon-bleu. That title of high distinction is reserved for the feminine sex. According to Lady Morgan (Sidney Owenson, 1841), in her “Book without a Name,” a cordon-bleu is defined as an honorary distinction conferred on the first class of female cooks in Paris, either in allusion to their blue aprons, or to the order whose blue ribbon was so long considered as the adequate recompense of all the highest merit in the highest classes.

The Fermier Général who built the palace of the Elysée became not more celebrated for his exquisite dinners than for the moral courage with which he attributed their excellence to his female cook, Marie, when such a chef was hardly known in[Pg 4] a French kitchen; for when Marie served up un petit diner délirant she was called for like other prime donne, and her health drunk by the style of Le Cordon Bleu.

One of the most famous of the bearers of the title was undoubtedly that wonderful Sophie who is so charmingly described in La Salle-à-manger du Docteur Véron. She was cook and politician too, and even Alexandre Dumas père did not disdain to dine with her at a dinner of her own cooking; and moreover eminent statesmen of the period consulted her about politics, her clear-headed simplicity and wide experience of popular sentiment rendering her opinions of considerable value. The editor adds that her name was not Sophie, but that her many friends will nevertheless easily recognize her.

The value of a good chef in a well-ordered household cannot be over-estimated. His tact, his experience, and his art go far to make life pleasant and easy. Moreover, a good cook is a direct aid to good health, for he uses none but the best materials, and, if he be of the highest rank of his[Pg 5] order, knows just how to assimilate those suave and subtle suggestions and flavourings which go so far to make cookery such as the great Careme (1828) called le genre mâle et élégant. Cooks were held in the highest estimation in Venice in the sixteenth century. Here is the beginning of a letter from one Allessandro Vacchi, a Venetian citizen, to an acquaintance of his, a cook and carver by profession: “Al magnifico Signor Padron mio osservandissimo il Signor Matteo Barbini, Cuóco e Scalco celeberrimo della città di Venetia.” In our own time honour to the profession is not lacking, for a little while ago the King decorated M. Ménager, his maître-chef, with the Royal Victorian Medal.

At the same time the competition of many rich folk for the services of some of the best-known chefs has made these artists, in some cases at least, place an extortionate value upon their ministrations. A very clever chef, reliable in everything except his sauces, in which he is slightly heterodox, was recently engaged by a nouveau riche at a salary far exceeding that which he paid to his private secretary.

[Pg 6]

In one of Matthew Bramble’s letters from Bath (“Humphry Clinker”) he refers to such a one as “a mushroom of opulence, who pays a cook seventy guineas a week for furnishing him with one meal a day.” Mushroom of opulence is good. That species of fungus is always with us. Dr. Kitchiner in his “Housekeeper’s Oracle” (1829) quotes from “The Plebeian Polished, or Rules for Persons who have unaccountably plunged themselves into Wealth.” A work of this nature, if published nowadays, should surely command a large sale, for the number of people who have “unaccountably plunged themselves into Wealth” seems to be multiplying rapidly. Most of them know how to feed. Few of them seem to have mastered the mystery of how to dine. “Man ist was man isst” says the German proverb, and there is no valid reason for spending fabulous sums on a dinner of out-of-the-season delicacies, when the good reasonable and seasonable things of this earth are ready and ripe for consumption.

At the same time, meanness has nothing[Pg 7] to recommend it. There is no credit in starving yourself or your guests. The difference between mere parsimony and economy has never been more deftly illustrated than in those pregnant sentences from Edmund Burke: “Mere parsimony is not economy. Expense, and great expense, may be an essential article in home economy. Economy is a distributive virtue, and consists, not in saving, but selection. Parsimony requires no providence, no sagacity, no powers of combination, no comparison, no judgment. Mere instinct, and that not an instinct of the noblest kind, may produce this false economy in perfection.”

This is very solid wisdom, because it bears in mind the great element of perspective in expense, which is so often forgotten or overlooked.

To revert to the preciousness and rarity of the really good female cook, to the artist in pots and pans. It was in 1833 that the Prince de Ligne, who had just lost his second wife, came to Paris to seek consolation. He lived temporarily in the Rue[Pg 8] Richelieu. One evening in passing the lodge he became aware of a peculiarly alluring odour of cooking. He saw the concierge, an old woman of sixty, bending eagerly over a battered stewpan on a small charcoal fire, stirring some mess which evidently was exhaling this delicious odour. The Prince was one of the affable kind. He asked the poor old lady for a taste of her dish, which he liked so much that he gave her a double louis, and asked her how it happened that with such eminent culinary genius she was reduced to the porter’s lodge. She told him that she had once been head cook to a cardinal-archbishop. She had married a bad man who had spent all her savings. Although very poor, she added with conscious pride, and no longer disposing of the full batterie of an archiepiscopal kitchen, she flattered herself she could manage with a few bits of charcoal and a méchante casserole to cook with the best of them. Next day the lodge was vacant, the old concierge being on her way to Belœil, the Prince de Ligne’s residence, near Mons, in Belgium, where she presided for fifteen[Pg 9] years over one of the best-appointed kitchens in the world.

Less fortunate than the Prince de Ligne was a middle-aged bachelor in Paris, a few years ago, who gave away an odd lottery ticket to his cook, a worthy and unprepossessing spinster. Shortly afterwards, to his amazement, he saw that this particular ticket had drawn the gros lot. He could not afford to part with such a valuable and valued servant, so he proposed marriage, was accepted, and duly became one with his cook before the maire with as little delay as possible. Directly after the marriage he asked his wife for the lottery ticket. “Oh, I gave that away,” she said, “to Jean, the coachman, to compensate him for our broken engagement.”

It has been the ambition of many highly placed men to become cooks. According to Miss Hill’s interesting book on Juniper Hall, and its colony of refugees, M. de Jaucourt is recorded to have said: “It seems to me that I have something of a vocation for cookery. I will take up that business. Do you know what our cook[Pg 10] said to me this morning? He had been consulting me respecting his risking the danger of a return to France. ‘But you know, monsieur,’ he said, ‘an exception is made in favour of all artists.’ ‘Very well then,’ concluded M. de Jaucourt, ‘I will be an artist-cook also.’”

A notable instance of the chef who took a pride in his art and could not understand any one referring to him as “a mere cook” is the delightful hero of Mr. H. G. Wells’s story of “A Misunderstood Artist” in his “Select Conversations with an Uncle.” “They are always trying to pull me to earth. ‘Is it wholesome?’ they say;—‘Nutritious?’ I say to them: ‘I do not know. I am an artist. I do not care. It is beautiful.’—‘You rhyme?’ said the Poet. ‘No. My work is—more plastic. I cook.’”

There was a famous cook too, Laurens by name, who was chef for a long time to George III, and who combined with his culinary skill a wonderful flair for objects of art, so that the King bought a large number of the beautiful things which are even now[Pg 11] at Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle on the advice of this same Laurens. It has been said of him that he rarely made a mistake in buying, and that he attended the principal picture and art sales on the Continent on behalf of his royal master.

Some cheerful noodles have had much to say anent the want of imagination of the modern chef. This is the most arrant blatherumskite. The chef, who is only, after all, a superior servant, paid (and well, too) to carry out the gastronomic ideas of his master, or, if he lack such ideas, to pander to his ignorance, too frequently arrogates to himself a culinary wisdom which is not justified by results. The chef need only be a thoroughly good cook. The ideas, the suggestions, the genius behind the pots and pans, come from the gastronomic student. Neither Brillat-Savarin nor Grimod de la Reynière was a cook—nor was Thomas Walker, G. A. Sala, or E. S. Dallas, but they were all notable authorities. And they inspired the culinary art of their times by their knowledge, invention, and discrimination.

[Pg 12]

As a matter of fact, our chefs are unimaginative—and a good job too; because when a chef, be he never so clever, begins to launch out on novelties of his own invention, he almost invariably comes to grief. A really good maître d’hôtel may occasionally suggest a new dish, but in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred it is merely a slight variation of something perfectly well known and appreciated. There may be a new garnishing, a trifling alteration in the manner of serving, and there is invariably a brand-new (and usually inappropriate) name, but the dish remains practically the same, despite its new christening-robe.

A fine joint of Southdown mutton has been recently renamed Béhague, but it remains sheep, and nothing is gained by the alteration save a further insight into the ignorance of the average chef. This is only a simple example, but it might be multiplied indefinitely. I have been served at a well-known restaurant with cutlets à la Trianon, which turned out to be our old and tried friend cutlets à la Réforme under[Pg 13] a new title. In a like manner, but at another restaurant, an ordinary and excellent mousse de jambon paraded as jambon à la Véfour; Heavens and the chef only know why; and the one won’t tell, and the other doesn’t know.

Béhague, by the way, is, so to say, chefs’ French, which has much in common with dog Latin, if one may be allowed the comparison. Béhague will not be found in a French dictionary, but it is the new nom de cuisine for fine-quality mutton (such as Southdown); it has only lately come into use, and there seems no particular reason for it. Probably it was invented in “a moment of enthusiasm,” as the barber-artist remarked when he made a wig that just fitted a hazel-nut.

There are several different kinds of bad language. That used by chefs and maîtres d’hôtel on their menus is one of the worst. They are incorrigibly ignorant—and glory in it. It is an undeniable fact that the average menu, whether at a club or restaurant, contains usually at least a brace of orthographic howlers, while at the private house,[Pg 14] an it boast a chef who writes the dinner programmes, the average is distinctly higher. I have encountered on an otherwise quite reputable card the extraordinary item Soufflet de fromage. The kind hostess had no intention of inflicting a box on the ears to the cheese, but had mistaken soufflet for soufflé. By such obvious errors are social friendships imperilled.

But I should like to go much further than this comparatively harmless example. No less an authority than Æneas Dallas in Kettner’s “Book of the Table” says: “It is a simple fact, of which I undertake to produce overwhelming evidence, that the language of the kitchen is a language ‘not understanded of the people.’ There are scores upon scores of its terms in daily use which are little understood and not at all fixed, and there is not upon the face of this earth an occupation which is carried on with so much of unintelligible jargon and chattering of apes as that of preparing food. Not only cooks, but also the most learned men in France have given up a great part of the language of the kitchen as beyond[Pg 15] all comprehension. We sorely want Cadmus amongst the cooks. All the world remembers that he taught the Greeks their alphabet. It is well-nigh forgotten that he was cook to the King of Sidon. I cannot help thinking that cooks would do well to combine with their cookery, like Cadmus, a little attention to the alphabet.”

It is easy, of course, to ridicule such obvious ineptitudes as a dish of “breeches in the Royal fashion with velvet sauce” (Culotte à la Royale sauce velouté) or “capons’ wings in the sun” (ailes de poularde au soleil), but these are but trifling offences compared to the egregious lapses of grammar, history, and good taste which disfigure our menus. There is no culinary merit in describing an otherwise harmless dish of salmon as saumon Liberté au Triomphe d’Amour. It is simply gross and vulgar affectation. Let the cooks do their cooking properly and all will be well. Their weirdly esoteric naming of edible food is an insult of supererogation to the intelligence of the diner.

At the same time, due credit must be given to the chef for the part he has played[Pg 16] in the general improvement of gastronomics and the art of feeding during the past two decades. The mere multiplication of restaurants is nothing; but the general improvement of the average menu is everything. Here, for instance, is the menu of a dinner of the year 1876, recommended by no less an authority than the late Fin Bec, Blanchard Jerrold, whose Epicure’s Year Books, Cupboard Papers, and Book of Menus are by way of being classics.

MENU.

Crécy aux Croûtons.

Printannier.

Saumon bouilli, sauce homard.

Filets de soles à la Joinville.

Whitebait.

Suprême de Volaille à l’écarlate.

Côtelettes d’Agneau aux concombres.

Cailles en aspic.

Selle de Mouton.

Bacon and beans.

Caneton.

Baba au Rhum.

Pouding glacé.

This was the dinner given by the late[Pg 17] Edmund Yates on the occasion of the publication of the World newspaper. Observe its heaviness, clumsiness, and want of delicacy. Three fish dishes are ostentatious and redundant; three entrées simply kill one another; the quails are misplaced before the saddle; the bacon and beans is, of course, a joke. Altogether it is what we should call to-day a somewhat barbarian meal. Contrast therewith the following artistically fashioned programme of a dinner given by the Réunion des Gastronomes; it is practically le dernier mot of the culinary art.

MENU.

Huîtres Royales Natives.

Tortue Claire.

Filets de Soles des Gastronomes.

Suprême de Poularde Trianon.

Noisettes d’Agneau à la Carême.

Pommes Nouvelles Suzette.

Sorbets à la Palermitaine.

Bécassines à la Broche.

Salade.

Haricots Verts Nouveaux à la Crème.

Biscuit Glacé Mireille.

Corbeille de Friandises.

Dessert.

[Pg 18]

Nothing could be lighter or more graceful. There is naught that is over-elaborate or indigestible; on the contrary, the various flavours are carefully preserved, and there is a subtle completeness about the whole dinner which is very pleasing.

It was the late lamented Joseph, of the Tour d’Argent, the Savoy, and elsewhere, who once said: “Make the good things as plain as possible. God gave a special flavour to everything. Respect it. Do not destroy it by messing.”

Joseph, who, by the way, was born in Birmingham, was a mâitre d’hôtel of genius, though even he had his little weaknesses, and merely to watch the play of his wrists whilst he was “fatiguing” a salad for an especially favoured guest was a lesson in inspired enthusiasm. His rebuke to a rich American in Paris is historic. The man of dollars had ordered an elaborate déjeuner, and whilst toying with the hors-d’œuvre carefully tucked his serviette into his collar and spread it over his waistcoat, as is the way with some careless feeders. Joseph, rightly enough, resented this want of[Pg 19] manners, and, approaching the guest, said to him politely, “Monsieur, I understand, wished to have déjeuner, not to be shaved.” The restaurant lost that American’s custom, but gained that of a host of nice and delicate feeders.

[Pg 20]

“La Cuisine n’est pas un métier, c’est un art, et c’est toujours une bonne fortune que la conversation d’un cuisinier: mieux vaut causer avec un cuisinier qu’avec un pharmacien. S’il n’y avait que de bons cuisiniers, les pharmaciens auraient peu de choses à faire, les médecins disparaîtraient; on ne garderait que les chirugiens pour les fractures.”—Nestor Roqueplan.

I am going to be very rude. Not one woman in a hundred can order a dinner at a restaurant. I’ve tried them, and I know. Not only can she not order a dinner with taste, discretion, and due appreciation of season, surroundings, and occasion; but she inevitably shows her character, or want of it, if she be allowed to choose the menu. The eternal feminine peeps out in the soup,[Pg 21] lurks designedly in the entrées, and comes into the full glare of the electric light in the sweets and liqueurs.

Let me explain. As a bachelor who is lucky enough to be asked out to many dinner parties, I have cultivated a slight reciprocative hospitality in the shape of asking my hostesses (and their daughters, if they have any) to dine with me at sundry restaurants. It is my habit to beg my guests to order the dinner, “because a woman knows so much more about these things than a mere man”; and all unwittingly the dear ladies invariably fall into the innocent little trap, wrinkle up their foreheads and study the carte, while I sit tight and study character.

Luckily my digestion is excellent. I have survived several seasons of this sort of thing, but I feel that the time is coming when I must really give it up and order the dinners myself.

The wife of a very important lawyer was good enough to dine with me at the Savoy recently. She is, I believe, a thoroughly good wife and mother, and, moreover, she[Pg 22] has a happy knack of humorous small talk. She graciously agreed to order our dinner—after the usual formula. The crême santé was all right—homely and healthy, if a trifle dull and uninteresting; but when we went on to boiled sole, mutton cutlets, and a rice pudding, I felt that the sweet simplicity of the Jane Austen cuisine was too much with us, and I recognized sadly that she was not imbued with the spirit of place; she mistook the Savoy for the schoolroom. Her forte was evidently decorous domesticity. Nevertheless, I had a good dinner.

Less fortunate was I in my experience with the eldest daughter of a celebrated painter. She was all for colour. “There is not enough colour in our drab London life,” she said; so, at the Carlton, she ordered Bortsch, because it was so pretty and pink; fish à la Cardinal, because of the tomatoes; cutlets à la Réforme, because she liked the many-coloured “baby-ribbons” of garnishing; spinach and poached eggs—“the contrast of colour is so daring, you know”; beetroot salad; a peach à la[Pg 23] Melba—“so artistic and musical”; and, of course, crême de menthe to accompany the coffee. It was a feast—of colour—and the food was thoroughly well cooked; but I was reminded of Thackeray’s chef, M. Mirabolant, who conceived a white dinner for Blanche Amory to typify her virginal soul.

Then there was an amiable and affected widow, whose mitigated woe and black voile frock were most becoming. She presumed, however, on her widowhood to order everything en demi-deuil, which meant that every dish from fish to bird was decorated with mourning bands of truffles. The thoughtful chef sent up the ice in the form of a headstone, and we refrained from Turkish coffee because French café noir was so much blacker.

The great Brillat-Savarin, speaking of female gourmets, said, “They are plump and pretty rather than handsome, with a tendency to embonpoint.” I confess that my experience leads me to disagree; the real female gourmet (alas, that she should be so rare!), broad-minded, unprejudiced,[Pg 24] and knowledgeable, is handsome rather than pretty, thin rather than stout, and silent rather than talkative. This, however, by the way.

Two schoolgirls did me the honour of dining with me at Prince’s not long ago, before going to the play. I gave them carte blanche to order what they liked, and this was the extraordinary result:—

Langouste en aspic.

Meringues Chantilly.

Consommé à la neige de Florence.

Selle de Chevreuil.

Gelée Macédoine.

Faisan en plumage.

Bombe en surprise.

Nid de Pommes Dauphine.

I ventured to suggest that there was a certain amount of fine confused feeding about this programme, that it was so heavy that even two hungry schoolgirls and a middle-aged bachelor might find it difficult to tackle, also that the sequence of dishes was not quite conventional. Eventually they blushingly explained that they had ordered all these things because they did[Pg 25] not know what any of them meant, and they wanted to find out—“besides, they’ve got such pretty names, and it will help us so much in our French lessons.” I reduced the formidable dimensions of the dinner, and there were no disastrous results.

I once had the temerity to invite a real lady journalist to dine with me at the Berkeley. I think that she writes as Aunt Sophonisba, or something of the sort, and her speciality is the soothing of fluttering hearts and the explaining of the niceties of suburban etiquette. Anyhow, she knows nothing about cookery, although I understand she conducts a weekly column entitled “Dainty Dishes for Delicate Digestions.” It was in July, and she said we might begin with oysters and then have a partridge. When I explained that owing to official carelessness these cates happened to be out of season, she waxed indignant and said that she thought “they were what the French call primeurs.” Nevertheless, she made a remarkably good hot-weather dinner, eating right through the menu, from the melon réfraichie to the petits fours. Women[Pg 26] who golf, lady journalists, and widows, I observe, have usually remarkably good appetites.

I recollect also an American actress who sang coon songs—and yearned for culture. We lunched at the Cecil, and when she espied on the card eggs à la Meyerbeer, she instantly demanded them because “he was a composer way back about the year dot, and I just love his music to ‘Carmen.’” She hunted through the menu for celebrated names, preferably historical, and ordered successively Sole à la Colbert, Poulet Henri Quatre, and Nesselrode pudding, because they reminded her of the time when she was studying French history.

With the keenest desire not to be thought disrespectful or ungallant, I really believe that, however well a woman may manage her household, her cook, her husband, and her kitchen expenses, she cannot order a dinner at a restaurant. Whether it be the plethora of choice, or the excitement of the lights and music, or awe of the maître d’hôtel and the sommelier, I do not know, but I am sure that the good hostess who[Pg 27] gives you a very eatable little dinner at her own house will make hash of the best restaurant carte du jour in her endeavours to order what she thinks is nice and appropriate.

In referring just now to the excellent Miss Jane Austen, I am reminded that eating and drinking play no small part in her delightful novels. Who does not remember Mrs. Bennet, who dared not invite Bingley to an important dinner, “for although she always kept a good table, she did not think anything less than two courses could be good enough for a man on whom she had such anxious designs, or satisfy the appetite and pride of one who had ten thousand a year.” The dinner eventually served consisted of soup, venison, partridges, and an unnamed pudding. And a very good meal too!

An American critic is of opinion that there is a surfeit of mutton in English literature. “It is boiled mutton usually, too.” Now boiled mutton is, to the critic, a poor sort of dish, unsuggestive, boldly and flagrantly nourishing, a most British[Pg 28] thing, which “will never gain a foothold on the American stomach.” This last is a vile phrase, even for an American critic, and suggests a wrestling match. The critic goes on: “The Austenite must e’en eat it. Roast mutton is a different thing. You might know Emma Woodhouse would have roast mutton rather than boiled; it is to roast mutton and rice pudding that the little Kneightleys go scampering home through the wintry weather.”

From Miss Austen to Mrs. Gaskell is no such very far cry. “We had pudding before meat in my day,” says Mr. Holbrook, the old-fashioned bachelor-yeoman in “Cranford.” “When I was a young man we used to keep strictly to my father’s rule: ‘No broth, no ball; no ball, no beef.’ We always began dinner with both, then came the suet puddings boiled in the broth with the beef; and then the meat itself. If we did not sup our broth, we had no ball, which we liked a deal better, and the beef came last of all. Now folks begin with sweet things, and turn their dinners topsy-turvy.”

[Pg 29]

What would such a one have said to our modern dinners, at home, or at a restaurant; a place which he probably would not comprehend at all, for, at any rate with us, the fashion of dining in public, especially with our women-folk, is a very recent innovation. The hearty individual of Mr. Holbrook’s time and type would have more sympathy with the frugalities of the La Manchan gentleman Cervantes drew, with his lean horse and running greyhound, courageous ferret, and meals of “duelos y quebrantes,” that strange dish, which Mr. Cunninghame Graham tells us “perplexed every translator of the immortal work.”

The modern restaurant is, I suppose, part and parcel of the evolutionary trend of the times. It has its advantages and its drawbacks. Its influence on public manners or manners in public (which are not altogether the same thing), are not entirely salutary. He was a wise person who once said, “Vulgarity, after all, is only the behaviour of others.” Go into any frequented restaurant at dinner-time, watch the men and women (especially the latter), how they eat,[Pg 30] talk, and observe their neighbours—et vous m’en direz des nouvelles! Our forbears, although, or perhaps because, they dined out less, or not at all, had a certain reticence of table manner which has been lost in succeeding generations. Be good enough to note the reception of a party of guests entering a full restaurant and making their way to their reserved table. Notice how every feminine eye criticizes the new-comers. Not a bow, nor a frill, nor a sleeve, nor a jewel, nor a twist of chiffon is unobserved. Talk almost ceases whilst the progress through the already filled tables takes place. The men of the party ask polite questions, and endeavour to continue the even tenor of the conversation, but the feminine replies are vague and malapropos. No woman seems able to concentrate her attention on talk whilst other women are passing. She must act the critic; note, observe, copy, or deride. These are our table manners of to-day. Not entirely pretty, perhaps; but typical and noteworthy.

The multiplication of restaurants continues, and yet, come to think of it, the [Pg 31] actual places where one lunches, dines, or sups, the “legitimate” houses, so to say, can be numbered on the fingers of both hands—including the thumbs. All the others are more or less esoteric. One can, possibly, dine as well in Soho as in the Strand, but there is no cachet about the dinner, and one never meets any one one knows, or if one does, one wishes one hadn’t.

Still, compared with our grandfathers’ times, things have vastly altered. In the “Epicure’s Almanack or Calendar of Good Living for 1815,” there is a list of over one hundred eating-houses of sorts, but the only ones that survive to this day are Birch’s of Cornhill; the “Blue Posts” in Cork Street; the “Cheshire Cheese,” Fleet Street; the “Golden Cross,” Charing Cross; Gunter’s of Berkeley Square; Hatchett’s in Piccadilly; the “Hummums” in Covent Garden; Long’s in Bond Street (better known as “Jubber’s”); the “Ship,” Charing Cross; the London Tavern; and “Sweeting’s Rents.”

Speaking of the music at a very well-known restaurant in town, a morning paper[Pg 32] said recently: “It is noticeable that many of the visitors occasionally stop talking and listen to the music.” This set me thinking. It is worth while listening to good music. Bad music we are better without. Good cooking and good conversation are natural concomitants, and mutually assist one another. Ergo, it seems obvious that good music and a good dinner are incompatible. It is rude to talk whilst musical artists are giving of their best for your delectation, and, at the same time, a dinner partaking of Wordsworth’s Peter Bell’s party in a parlour “all silent and all damned” is contrary to the best gastronomic traditions. Thus I think I have the musical diner in an impasse.

Speaking from memory, among the best dozen restaurants in London there is music in every one save three; I am therefore bound to conclude that it is merely a question of supply and demand, and that I am in a minority. I overheard a quaint protest the other night at a restaurant where the music is particularly loud, blatant, and objectionable. A man and, presumably, his wife were dining together, and were[Pg 33] evidently anxious to keep up their conversation on some mutually interesting topic. During a lull in the clatter and noise I heard the woman’s voice say, “I do wish they would play more quietly, one really cannot hear what one is eating.”

How many casual diners at the Carlton could hum or whistle that fine old air? Probably not one—not even M. Jacques. And yet it is about the only really appropriate and legitimate tune to which Britons ought to feed. What do we get instead? Musical-comedy selections, languorous waltzes, cornet solos, coon songs, and an occasional czardas. Is music really an aid to digestion, or is it designed, like the frills on the cutlets, to induce us to ignore the imported mutton in favour of the trimmings?

It is tolerably certain that music with dinner (at a restaurant, for the ordinary diner) was unknown in England before 1875. In the previous year the late George Augustus Sala, who knew most things worth[Pg 34] knowing—gastronomically—wrote an article in a monthly magazine on dinner music, and refers to it as existing only in royal palaces. Very soon afterwards, however, it was offered to anybody who could afford to pay a few shillings for a set dinner amid clean and appetizing surroundings. Subject to correction, it is fairly certain that the first place in London where they provided music at dinner was the Holborn Restaurant, which had been a swimming-bath, a dancing-casino, and other things. The example was speedily followed, and very soon bands sprang up like mushrooms right and left, at every restaurant which made any pretence of attracting the multitude.

The Criterion started glee-singers, although this was perhaps more directly an outcome of Herr Jongmanns’ boys’ choir at Evans’ in Covent Garden.

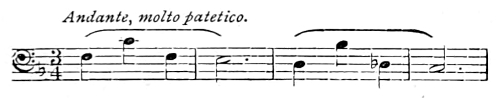

Nearly every restaurant in London nowadays has a band, and go where you will, such spectacles are offered you as a man with music in his soul trying to take his hot soup in jig time, because the band is playing prestissimo forsooth, and getting very[Pg 35] red in the face whilst so doing. Then will follow the whitebait, and the band, just out of pure cussedness, plays a languishing slow movement, whereupon the musical diner is obliged to eat his whitebait andante, and the dear little fish get quite cold in the process.

Over in Paris, Berlin, and on the Riviera it is even worse. The restaurateurs there encourage a wild, fierce race of hirsute ruffians called Tsiganes, who are supposed to be Hungarian gipsies: “A nation of geniuses, you know; they can’t read a note of music, and play only by ear!” That’s just the trouble of it—because their ears are often all wrong. There is absolutely nothing less conducive to a good appetite than to watch these short-jacketed, befrogged, Simian fiddlers playing away for dear life the Rakoczy March or a maltreated Strauss waltz, and ogling à la Rigo[Pg 36] any foolish female who seems attracted by them. It is on record that an Englishman once approached the leader of such a band in a Paris restaurant and asked him the name of the dance he had just been playing. “Sure, an’ I don’t know, yer honour,” was the reply, “but I’m thinking it’s a jig.” All the Hungarians do not come from Hungary.

Curiously enough, there is an old-time connexion between music and dinner, although not precisely as we understand either. In the great houses of the seventeenth century dinner was announced by a concert of trumpets and drums, or with blasts from a single horn, blown by the head huntsman. The music of huntsmen running in upon their quarry was the music which declared the venison and wild boar ready for the trenchers. Blown to announce the coming of dinner and supper, the horn was also wound to celebrate the virtue of particular dishes. The nobler creatures of the chase were seldom brought to table without notes from the trumpet. Musical honours were accorded to the peacock, the swan, the sturgeon, and[Pg 37] the turbot. The French used to say, “Cornez le diner,” i.e. “Cornet the dinner”—hence we derive our corned beef.

But to return to our own times; things have come to such a pass, musically speaking, that the suburbanest of suburban ladies shopping of an afternoon in Oxford Street cannot drink her cup of tea without a band in the basement. It is quite humorous to listen to a selection from “La Bohême” punctuated by “Ten three-farthings, my dear, and cheap at that,” or “You must really tell Ethel to have a silk foundation”; but women are such thoroughly musical beings that they seem to accommodate themselves to all sorts of incongruities.

The old gourmets, who knew how to dine, loved music in its right place and at the right time, but that was not at dinner. Rossini, the great composer, was one of them. He loved good cheer and he wrote wonderful music—but he never mixed the two. It is passing strange that various ways of cooking eggs have been called after various composers. Thus we have œufs à la Meyerbeer, à la Rossini, à la Wagner, even[Pg 38] à la Sullivan. Why music and eggs should be thus intimately connected is somewhat of a puzzle.

The late Sir Henry Thompson, who married a musician, and the late Joseph of the Savoy, who was an artist at heart, both despised music at dinner. The former said that it retarded rather than assisted digestion; and the latter remarked that he could never get his cutlets in tune with the band. Either the band was flat and his cutlets were sharp, or vice versâ.

There are a few restaurants in London, some half-dozen at most, where one can dine in peace, undisturbed by potage à la Leoncavallo, poisson à la Rubinstein, rôti à la Tschaikowski, and entremet à la Chaminade. But it would be unwise to say where they are, because it might attract crowds and induce the proprietors to start a band. And, after all, a dinner-table is not a concert platform.

In the “Greville Memoirs” (1831) you may read that dinners of all fools have as good a chance of being agreeable as dinners of all clever people: at least the former are[Pg 39] often gay, and the latter are frequently heavy. Nonsense and folly gilded over with good breeding and les usages du monde produce often more agreeable results than a collection of rude, awkward, intellectual powers. This must be our consolation for enjoying “gay” dinners.

In a translation from Dionysius, through Athenæus, occur these lines:—

This shows a nice appreciation of the duties of the all-round cook, supervised by a knowledgeable master, and is preferable to the fastidiousness of Sir Epicure Mammon in “The Alchemist,” who leaves the best fare, such as pheasants, calvered salmon, knots, godwits, and lampreys, to his footboy; confining himself to dainties such as cockles[Pg 40] boiled in silver shells, shrimps swimming in butter of dolphin’s milk, carp tongues, camels’ heels, barbels’ beards, boiled dormice, oiled mushrooms, and the like. One must go back to Roman cookery, via Nero and others, for such gustatory eccentricities, a number of which, one may shrewdly believe, were not precisely what they are described to be in modern English. Do we not know, for instance, that a famous Roman cook (who was probably a Greek), having received an order for anchovies when those fish were out of season, dexterously imitated them out of turnips, colouring, condiments, and the inevitable garum; as to the exact and unpleasant constituents of which, authorities, including the great Soyer, differ considerably.

The result cannot have been of the nature described by Miss Lydia Melford in “Humphry Clinker,” who called the Bristol waters “so clear, so pure, so mild, so charmingly mawkish.”

[Pg 41]

“Drinking has indeed been sung, but why, I have heard it asked, have we no ‘Eating Songs’?—for eating is, surely, a fine pleasure. Many practise it already, and it is becoming more general every day. I speak not of the finicking joy of the gourmet, but the joy of an honest appetite in ecstasy, the elemental joy of absorbing quantities of fresh, simple food—mere roast lamb, new potatoes, and peas of living green. It is, indeed, an absorbing pleasure.” R. le Gallienne.

The quotation with which I have headed this chapter, though appropriate enough in a sense, disproves itself in the assertion. We have “Eating Songs” in plenty, both in our own language and in foreign tongues, but they have been neglected and spurned, and for that reason they well repay a little[Pg 42] enterprising research. Here and there, throughout our literature, are gems of gastronomical versification, and it is, in fact, impossible to do more than indicate a tithe of the treasures that may be unearthed with a very little trouble and patience.

Among the anthologies of the future, the near future maybe, is undoubtedly the Anthology of the Kitchen. It is ready written, and only remains to be gathered. There is barely a poet of note who could not be laid under contribution. Shakespeare, Byron, Béranger, Browning, Burns, Coleridge, Crabbe, Dryden, Goethe, Heine, Landor, Prior, Moore, Rogers, and Villon are the first chance names to occur, but there are many more who might be cited with equal justice.

Thackeray wrote verses on Bouillabaisse; which it would be absurd to quote, so well are they known. Méry, Alexandre Dumas, Th. de Banville, Th. Gautier, and Aurélien Scholl collaborated, under the editorship of Charles Monselet (himself a gastronomic poet of no mean order), in a little book published in 1859 under the title “La Cuisinière[Pg 43] Poétique.” Five years later there appeared in Philadelphia “A Poetical Cook Book,” by J. M. M., with charming rhymed recipes for such things as stewed duck and peas:—

The poetical author dilates too upon buckwheat cakes and oatmeal pudding, and quotes Dodsley on butter and Barlow on hasty pudding. Sydney Smith’s recipe for a salad is only too well known, and it may be hoped that it is not often tried, because from a gastronomic point of view it is a dire decoction. Arthur Hugh Clough in “Le Diner” (Dipsychus) has this entirely charming verse:—

Nearly two hundred years ago (in 1708, to be precise) Dr. William King wrote “The[Pg 44] Art of Cookery,” in imitation of Horace’s “Art of Poetry”; in the original edition it was advertised as being by the author of “A Tale of a Tub,” but although King was a friend of Swift, there seems to have been no authority to make use of his name. In the second edition, in the following year, some letters to Dr. Lister are added, and the title page ascribes the poem to “the Author of the Journey to London,” who dedicates it—or, rather, “humbly inscribes” it—to “The Honourable Beefsteak Club.” This edition has an exquisitely engraved frontispiece by M. Van der Gucht.

In the fifth volume of Grimod de la Reynière’s entrancing “Almanach des Gourmands” (1807) there is a poetical epistle d’un vrai Gourmand à son ami, l’Abbé d’Herville, homme extrêmement sobre, et qui ne cessoit de lui prêcher l’abstinence. These are a few of his lines:—

Subsequent volumes contain many poetical[Pg 45] references. There is even a hymn to Epicurianism, a fable gourmande et plus morale encore, entitled “Les Œufs; a logogriphe; several chansons; and a boutade.” Mortimer Collins, in “The British Birds,” has an exquisitely humorous tourney of three poets who respectively sing the praises of salad; and the late Dr. Kenealy wrote a book (in 1845) called “Brallaghan, or the Deipnosophists,” in which he tunes his lyre in praise of good food—and Irish whisky. Although Sydney Smith’s salad mixture is useless, his verses entitled “A Receipt to Roast Mutton” are excellent, particularly this verse:—

An anonymous author has given us the immortal lines:—

[Pg 46]

That they are absolutely true every Feinschmecker, as the Germans say, is bound to admit. The famous Cheshire Cheese pudding has not been without its laureate, one J. H. Wadsworth, who opens his pæan thus:—

The leg of mutton has not lacked its devotees from Thackeray’s—

to Berchoux’ praise of the gigot—

Sir John Suckling contributes to the poetic garland in his lines:—

[Pg 47]

And an anonymous Scotch poet indites the following ode to luncheons:—

A well-known French critic, Achille (not Octave) Uzanne, has compiled a little collection of menus and receipts in verses, with a notable preface by Chatillon-Plessis, which includes poems on such thrilling subjects as jugged hare, lobster in the American fashion, Charlotte of apples, truffles in champagne, epigrams of lamb, mousse of strawberries, and green peas. A more recent American poetaster has published during the[Pg 48] last few years “Poems of Good Cheer,” which are in the manner of fables, such as that of the man who “Wanted Pearls with his Oysters,” and the busy broker “Who had no time to eat,” and consequently acquired dyspepsia.

Lord Byron too may be allowed to have his say:—

One of the most ambitious efforts in the culinary-poetic line is, undoubtedly, “La Gastronome, ou l’homme des Champs à Table; poème didactique en quatre chants, par J. Berchoux, 1804,” wherein is set forth, at some length—firstly, the history of cooking; then the order of the services; and lastly, some fugitive pieces which allude to the gay science in choice and poetic terms. The book is enriched with[Pg 49] some exquisite copper-plate engravings by Gravelot, Cochin, and Monsiau. The lines addressed by the author to his contemporaries warning them against the “repas monstreux des Grecs et des Romains” are full of repressed dignity and good sound common sense. One puts down the book with a sense of poetical-gastronomical repletion.

The poetic afflatus has possessed most great cooks, but none with more practical application than the immortal Alexis Soyer, the hero of the Crimea and the Reform Club, who, on the death of his wife, a clever amateur artist, wrote this simple and witty epitaph, “Soyez tranquille.” Gay’s poem on a knuckle of veal is also worthy of record, and an anonymous American poet has immortalized the duck in four pregnant verses.

A very modern poet who writes over the initials of M. T. P. has four charming verses on the propriety of ladies wearing their hats whilst dining. The second and third stanzas read as follows:—

[Pg 50]

Some folks who are not yet very old may remember a quaint part-song or quartette for male voices, entitled “Life is but a Melancholy Flower,” which was sung alternately somewhat in this fashion:—

It had much deserved success in its day.

An old recipe for the roasting of a swan is very fairly summed up in these lines:—

[Pg 51]

TO ROAST A SWAN

THE GRAVY

This poem has been attributed to Mr. George Keech, chef of the Gloucester Hotel at Weymouth—of course a famous breeding place for swans.

[Pg 52]

The following recipe for making a “soft” cheese is said to be by Dr. Jenner:—

In praise of the best food in the world—plain British roast and boiled—Mr. G. R. Sims has dilated in his weekly columns; a verse from his perfectly correct and strict[Pg 53] “Ballade of New-Time Simpson’s” is well worth quoting:—

The “Envoi,” which commences most cleverly according to traditional rule, runs as follows:—

To come back to recipes, here is one for the famous Homard à l’Amèricaine written by the chef of the Grand International Hotel at Chicago, who is quite annoyed with M. Rostand for his obvious plagiarism in “Cyrano de Bergerac.”

[Pg 54]

COMMENT ON FAIT LE HOMARD À L’AMÉRICAINE

Many curious old poems may be found by careful delving in the books our great-grandfathers used to read, and which we ought to read, but don’t. For instance, the Roxborough Ballads contain a delightful poem briefly entitled “The Cook-Maid’s Garland: or the out-of-the-way Devil: shewing how[Pg 55] four highwaymen were bit by an ingenious cook-maid” (1720). There is a still older ballad in the same collection called “The Coy Cook-Maid, who was courted simultaneously by Irish, Welch, Spanish, French and Dutch, but at last was conquered by a poor English Taylor”; this is in blackletter, and is dated 1685.

A French lady with a happy knack of verse has written the following rhymed recipe for

SAUCE MAYONNAISE

Under the title of “Women I have never married,” O. S. of “Punch” writes delightfully[Pg 56] on the lady who knew too much about eating. This is one of his verses:—

The following couplets are by—I think—an American author.

The Old Beef Steak Society, otherwise known as the Sublime Society of Beef Steaks, and of which the full history has too often appeared in print, entertained the Prince of Wales, afterwards George IV, on his election as a member; the following is a verse of a song written in honour of the occasion by the poet-laureate to the Society, Captain Charles Morris of “Pall Mall” fame:—

I venture to think that this little excerpt from Lafcadio Hearn’s “Kokoro” is worthy of record here as a piece of real poetry in[Pg 58] prose. It is from a story called “The Nun of the Temple of Amida.” “Once daily, at a fixed hour, she would set for the absent husband, in his favourite room, little repasts faultlessly served on dainty lacquered trays—miniature meals such as are offered to the ghosts of the ancestors and to the gods. (Such a repast offered to the spirit of the absent one loved is called a kagé-sen, lit. ‘shadow-tray.’) These repasts were served at the east side of the room, and his kneeling-cushion placed before them. The reason they were served at the east side was because he had gone east. Before removing the food, she always lifted the cover of the little soup-bowl to see if there was vapour upon its lacquered inside surface. For it is said that if there be vapour on the inside of the lid covering food so offered, the absent beloved is well. But if there be none, he is dead, because that is a sign that his soul has returned by itself to seek nourishment. O-Toyo found the lacquer thickly beaded with vapour day by day.”

It would be unfair to omit mention of Molière, who so often and wisely devotes[Pg 59] attention to the culinary craft, for which, indeed, he had a high appreciation. Did he not read his plays to his cook? A typical passage is that from his “Femmes Savantes,” when Chrysale expatiates to Philaminte and Bélise.

Very few people, I am afraid, read the entirely delightful verse of Mortimer Collins, poet, journalist, novelist, epicure (in the best sense), and country-lover—all in one. He was among the nowadays less-known masters of gastronomics, a man who, although no cook himself, knew by intuition and experience just what was right, and if it were wrong, just why it was wrong. His[Pg 60] novels and poems, although very unequal, do not deserve to be forgotten, for they contain many fine, thoughtful, and beautiful passages. His burlesque of Aristophanes, “The British Birds,” is, in its way, a masterpiece. He wrote much and well on cookery and dining, both in prose and verse. Here follows one of his sonnets from a sequence addressed to the months—from a gastronomic point of view.

JUNE

The “Minora Carmina” of the late[Pg 61] C. C. R., whose verse has much of the charm of J. K. S. and C. S. Calverley, contains a few verses anent the pleasure of dining out, which are headed

NUNC EST COENANDUM

It would be easy to extend this list indefinitely, but enough is as good as a feast.

[Pg 62]

“I could digest a salad gathered in a churchyard as well as in a garden. I wonder not at the French with their dishes of frogs, snails, and toadstools; nor at the Jews for locusts and grasshoppers; but being amongst them make them my common viands, and I find they agree with my stomach as well as theirs.”

Sir Thomas Browne, “Religio Medici.”

We have it on the authority of Chaucer that salad is cooling food, for he says:—

That the eating of green meat is and always has been closely bound up with healthy human life is a fact which needs no demonstration; but the constantly recurring[Pg 63] references to it in the literature of all ages would seem to point the moral in so far as salads must always have appealed peculiarly to those leading a more or less sedentary life.

In a serious Biblical commentary of the eighteenth century, Baron von Vaerst, a German savant, refers to Nebuchadnezzar’s diet of grass as a punishment which did not in any way consist in the eating of salad, but in the enforced absence of vinegar, oil, and salt. That salad adds a zest to life is proved by St. Anthony, who said that the pious old man, St. Hieronymus, lived to the green old age of 105, and during the last ninety years of his life existed wholly upon bread and water, but “not without a certain lusting after salad.” This is confirmed by St. Athanasius.

In Shakespeare’s “Henry VI,” Jack Cade remarks that a salad “is not amiss to cool a man’s stomach in the hot weather.” Cleopatra too refers to her “salad days, when she was green in judgment, cool in blood.” In “Le Quadragesimal Spiritual,” a work on theology published in Paris in 1521, these lines occur:—

[Pg 64]

All writers agree as to the cooling properties of salads, and particularly lettuce, on the blood. In his “Acetaria: a Discourse of Sallets” (1699), John Evelyn says that lettuce, “though by Metaphor call’d Mortuorum Cibi (to say nothing of Adonis and his sad Mistress) by reason of its soporiferous quality, ever was and still continues the principal Foundation of the universal Tribe of Sallets, which is to Cool and Refresh. And therefore in such high esteem with the Ancients, that divers of the Valerian family dignify’d and enobled their name with that of Lactucinii.” He goes on to say that “the more frugal Italians and French, to this Day, Accept and gather Ogni Verdura, any thing almost that’s Green and Tender, to the very Tops of Nettles; so as every Hedge affords a Sallet (not unagreeable) season’d with its proper Oxybaphon of Vinegar, Salt, Oyl, &c., which doubtless gives it both the Relish and Name[Pg 65] of Salad, Ensalade, as with us of Sallet, from the Sapidity, which renders not Plants and Herbs alone, but Men themselves, and their Conversations, pleasant and agreeable.”

In praise of Lettuce he has much to say, and waxes almost dithyrambic as to its virtues. “It is indeed of Nature more cold and moist than any of the rest; yet less astringent, and so harmless that it may safely be eaten raw in Fevers; for it allays Heat, bridles Choler, extinguishes Thirst, excites Appetite, kindly Nourishes, and above all represses Vapours, conciliates Sleep, mitigates Pain; besides the effect it has upon the Morals. Galen (whose beloved Sallet it was) from its pinguid, subdulcid and agreeable Nature, says it breeds the most laudable blood.”

And again: “We see how necessary it is that in the composure of a Sallet every plant should come in to bear its part without being overpowered by some herb of a stronger taste, but should fall into their place like the notes in music.”

[Pg 66]

Here is a salad recipe, temp. Richard II.

Take parsel, sawge, garlyc, chibolles, oynons, lettes, borage, mynte, poirettes, fenel, and cressis; lave and waithe hem clene, pike hem, plucke hem smalle wyth thyne honde, and myng hem wel wyth rawe oyl, lay on vynegar and salt and serve ytt forth.

This must have been a strong salad, and full-flavoured rather than delicate. “Honde” is of course “hand,” and to “myng” is to mix. The etymology of the recipe is interesting.

Old Gervase Markham, in his “English Housewife,” has this quaint account of how to make a “Strange Sallet.”

First, if you would set forth any Red flower, that you know or have seen, you shall take your pots of preserved Gilly-flowers, and suting the colours answerable to the flower, you shall proportion it forth, and lay the shape of the Flower in a Fruit dish, then with your Purslane leaves make the Green Coffin of the Flower, and with the Purslane stalks make the stalk of the Flower, and the divisions of the leaves and branches; then with the thin slices of Cucumers, make their leaves in true proportions, jagged or otherwise; and thus you may set forth some full blown, some half blown and some in the bud, which will be pretty and[Pg 67] curious. And if you will set forth yellow flowers, take the pots of Primroses and Cowslips, if blew flowers, then the pots of Violets or Buglosse flowers, and these Sallets are both for shew and use, for they are more excellent for taste, than for to look on.

Another variety of old “Sallet” is referred to in “The Gentlewoman’s Delight” (1654), which instructs one

How to make a Sallet of all manner of Hearbs. Take your hearbs, and pick them clean, and the floures; wash them clean, and swing them in a strainer; then put them into a dish, and mingle them with Cowcumbers, and Lemons, sliced very thin; then scrape on Sugar, and put in Vinegar and Oil; then spread the floures on the top; garnish your dish with hard Eggs, and all sorts of your floures; scrape on Sugar and serve it.

An even earlier work, Cogan’s “Haven of Health” (1589), has the following reference: “Lettuse is much used in salets in the sommer tyme with vinegar, oyle, and sugar and salt, and is formed to procure appetite for meate, and to temper the heate of the stomach and liver.”

Montaigne recounts a conversation he had with an Italian chef who had served in[Pg 68] the kitchen of Cardinal Caraffa up to the death of his gastronomic eminence. “I made him,” he says, “tell me something about his post. He gave me a lecture on the science of eating, with a gravity and magisterial countenance as if he had been determining some vexed question in theology.... The difference of salads, according to the seasons, he next discoursed upon. He explained what sorts ought to be prepared warm, and those which should always be served cold; the way of adorning and embellishing them in order to render them seductive to the eye. After this he entered on the order of table-service, a subject full of fine and important considerations.”

An excerpt from “a late exquisite comedy” called The Lawyer’s Fortune, or Love in a Hollow Tree, is quoted by Dr. King (1709):—

Mrs. Favourite. Mistress, shall I put any Mushrooms, Mangoes, or Bamboons into the Sallad?

Lady Bonona. Yes, I prithee, the best thou hast.

Mrs. Favourite. Shall I use Ketchop or Anchovies in the Gravy?

Lady Bonona. What you will!

[Pg 69]

A quaint old book on Salads is entitled “On the Use and Abuse of Salads in general and Salad Plants in Particular,” by Johann Friedrich Schütze, Doctor of Medicine, and Grand-Ducal Saxe-Coburg-Meiningen, Physician at Sonnenburg and Neuhaus: Leipzig, 1758. The learned doctor adopts the classical division of humanity into the Temperamentum Sanguineum, or warm and damp, the Cholericum, or warm and dry, the Phlegmaticum, or cold and damp, and the Melancholicum, or cold and dry. To each of these classes a particular form of Salad applies, and none other.

When Pope Sixtus the Fifth was an obscure monk he had a great friend in a certain lawyer who sank steadily into poverty what time the monk rose to the Papacy. The poor lawyer journeyed to Rome to seek aid from his old friend the Pope, but he fell sick by the wayside and told his doctor to let the Pope know of his sad state. “I will send him a salad,” said Sixtus, and duly dispatched a basket of lettuces to the invalid. When the lettuces were opened money was found in their hearts. Hence the Italian[Pg 70] proverb of a man in need of money: “He wants one of Sixtus the Fifth’s salads.”

Fourcroy and Chaptal, notable chemists of the end of the eighteenth century, unite in praise of salads, and have written disquisitions on the dressing thereof; and Rabelais opines that the best salad-dressing is Good Humour, which is just the sort of thing that one might expect from him. His references to salad are numerous, and in the one oft-quoted case humorously apposite.

In the olden time salads were mixed by pretty women, and they did it with their hands. This was so well understood that down at least to the time of Rousseau (Littré gives a quotation from the “Nouvelle Heloise,” VI. 2) the phrase Elle peut retourner la salade avec les doigts was used to describe a woman as being still young and beautiful. “Dans le siècle dernier,” says Littré, “les jeunes femmes rétournaient la salade avec les doigts: cette locution a disparu avec l’usage lui-même.”

Among the gastrological Italian authors of the seventeenth century I must refer to Salvatore Massonio, who wrote a great work[Pg 71] on the manner of dressing salads, entitled “Archidipno, overo dell’ Insalata e dell’ uso di essa, Trattato nuovo Curioso e non mai più dato in luce. Da Salvatore Massonio, Venice, 1627.” The British Museum copy, by the way, belonged to Sir Joseph Banks. As was usual in those leisurely and spacious times, there is a most glowing dedication beginning thus: “A Molto Illustri Signori miei sempre osservandissimi i Signori fratelli Ludovico Antonio e Fabritio Coll’ Antonii.” There is also a compendious bibliography of 114 authors consulted and mentioned in this work, which, indeed, is of considerable importance and of great interest.

Every one knows the oft-told tale of the French emigré who went about to noblemen’s houses mixing delicate salads at a high fee. Most authorities refer to him as d’Albignac, although Dr. Doran, in his “Table Traits,” calls him le Chevalier d’Aubigné; but Grenville Murray, who generally knew what he was writing about, says that his name was Gaudet. However, that matters little. He, whoever he was, appears to have been an enterprising hustler[Pg 72] of the period, and it is recorded that he made a decent little fortune on which he eventually retired to his native land to enjoy peace and plenty for the remainder of his days.

In Mortimer Collins’s “The British Birds, by the Ghost of Aristophanes” (1872), there is a poetic tourney between three poets for the laureateship of Cloud-Cuckooland; the subject is “Salad.” The poet with the “redundant brow” sings:—

[Pg 73]

The poet with the “redundant beard” chants next.

The poet of “the redundant hair” then sings his lay in Tennysonian-Arthurian lines, and is ultimately awarded the laureateship of Cloud-Cuckoo-Town.

The verses do not show poor Collins at his best, and are only interesting as relating to the subject of salad. Other songs of his have never been excelled in a certain delicate charm of fancy and quaint turns of versification.

[Pg 74]

Many salads have been mixed on the stage; the most famous perhaps is the Japanese salad which occurs in Alexandre Dumas fils’ “Francillon” (produced at the Théâtre Français, 17 January, 1887). It is not orthodox, and, even when deftly mixed, not particularly nice, the flavours being coarsely blended. Annette de Riverolles, inimitably played by Reichemberg of the smiling teeth, dictates the recipe to Henri de Symeux, originally acted by Laroche. Here is the passage:—

Annette. You must boil your potatoes in broth, then cut them into slices, just as you would for an ordinary salad, and whilst they are still lukewarm, add salt, pepper, very good olive oil, with the flavour of the fruit, vinegar....

Henri. Tarragon?

Annette. Orleans is better, but it is not important. But what is important is half a glass of white wine, Château-Yquem, if possible. Plenty of finely-chopped herbs. Now boil some very large mussels in a small broth (court-bouillon), with a head of celery, drain them well and add them to the dressed potatoes. Mix it all up delicately.

Thérèse. Fewer mussels than potatoes?

Annette. One-third less. The flavour of the mussels must be gradually felt; it must not be anticipated, and it must not assert itself.

[Pg 75]

Stanislas. Very well put.

Annette. Thank you. When the salad is finished, mixed....

Henri. Lightly....

Annette. Then you cover it with slices of truffles, like professors’ skull-caps.

Henri. Boiled in champagne.

Annette. Of course. All this must be done a couple of hours before dinner, so that the salad may get thoroughly cold before serving it.

Henri. You could put the salad-bowl on ice.

Annette. No, no. It must not be assaulted with ice. It is very delicate, and the different flavours must combine peacefully. Did you like the salad you had to-day?

Henri. Delicious!

Annette. Well, follow my recipe and you will make it equally well.

A few years ago Mr. Charles Brookfield mixed an admirable salad on the stage of the Haymarket in the course of his clever monologue “Nearly Seven.” On 31 January, 1831, “La salade d’oranges, ou les étrennes dans la mansarde,” by M. M. Varin and Desvergers, was played at the Palais Royal. The first-named author was a sort of gastronomic playwright, for he wrote plays called “Le cuisinier politique,” “J’ai mangé mon ami,” and others.

[Pg 76]

In the Bohemian quarter of Paris, not so very many years ago, the students of the plein air school, the Paysagistes, used to sing this song at their convivial meetings:—

“When summer is icumen in,” one naturally turns to the cooling salad, the refreshing salmon mayonnaise, and the concomitant delights of mid-season entertaining. Regularly at that time of the year learned pundits in the daily papers tell us with portentous gravity what we ought to eat and what we ought to let alone. All this is the direst nonsense. A man or a woman of sense will eat that for which he or she feels inclined, and will have the requisite gastronomic gumption to avoid heating dishes which are unseasonable and unpalatable.

[Pg 77]

With all changes of the weather sensible people accommodate their diet to the meteorological conditions; fish is preferable to meat, and fruit plays its strong suit, because its cooling juices are just what we yearn to dally with when our appetites are a little under the weather. All this is axiomatic. Of salads in particular. I should like to give here and now the recipe of a salad which I have found most soothing and comforting in hot weather. I may, perhaps, be permitted to act as godfather and christen it “Vanity Fair Salad.” It is quite simple and wholesome and toothsome. Here followeth the recipe.

Vanity Fair Salad.—Take eight to ten cold cooked artichoke bottoms (fonds d’artichauts), fresh, not preserved, and the yellow hearts of two young healthy lettuces (cœurs de laitue). Break them into pieces with a silver fork or your fingers (on no account let them be touched by steel); add a not too thinly sliced cucumber, peeled; toss these together. Let them stand for half an hour; then drain off all the water. Now add two or three tablespoonfuls of pickled red cabbage, minus all vinegar, and a dozen sliced-up radishes. Add the dressing. As to this I prefer not to dogmatize. My own mixture is three and a half tablespoonfuls[Pg 78] of the very best Nice olive oil to one of wine vinegar and one-half of tarragon, with salt, pepper, French mustard, and three drops of Tabasco sauce. But this is a matter of opinion, and I insist on nothing except the total avoidance of that horrible furniture-polish mixture sold in quaint convoluted bottles, and humorously dubbed “salad sauce.” Just before serving sprinkle the salad with chopped chervil and a suspicion of chives.

Our great-grandmothers had various and curious recipes for the assuagement of summer fevers and megrims of that nature. From an old volume of “The Lady’s Companion, or an infallible Guide to the Fair Sex,” published anonymously in 1743, I cull the following recipe for “Gascoign Powder.”

Take prepar’d Crabs’ Eyes, Red Coral, White Amber, very finely powdered, of each half an Ounce; burnt Hartshorn, half an Ounce; Pearls very finely powdered, and Oriental Bezoar, an Ounce of each; of the black Tops of Crabs’ Claws, finely powdered, four Ounces. Grind all these on a Marble Stone, till they cast a greenish Colour; then make it into Balls with Jelly made of English Vipers Skins, which may be made, and will jelly like Hartshorn.

Of course, this was never meant to be taken seriously, but the old cookery-book[Pg 79] compilers always thought that a few of these pseudo-medieval recipes, assumed to have been compounded by the wise men of old, added a certain dignity to their otherwise quite harmless volumes.

The late Sir Henry Thompson recommends that the host or hostess should mix the salad, because not many servants can be trusted to execute the simple details.

Mixing one saltspoon of salt and half that quantity of pepper in a tablespoon which is to be filled three times consecutively with the best fresh olive oil, stirring each briskly until the condiments have been thoroughly mixed and at the same time distributed over the salad, this is next to be tossed thoroughly but lightly, until every portion glistens, scattering meantime a little finely chopped fresh tarragon and chervil, with a few atoms of chives over the whole, so that sparkling green particles spot, as with a pattern, every portion of the leafy surface. Lastly, but only immediately before serving, one small tablespoonful of mild French, or better still, Italian red-wine vinegar, is to be sprinkled over all, followed by another tossing of the salad.

“La Salade de la Grande Jeanne” is a pretty child’s story by the prolific writer, P. J. Stahl (really P. J. Hetzel), telling of[Pg 80] the friendship of a tiny tot named Marie and a cow named Jeanne. They were born on the same day, but the calf grew to a big cow long before Marie became a big girl, but they remained firm friends, and Marie always took Jeanne to the pasture and Jeanne in return took care of Marie.

One day Marie’s little brother Jacques had a brilliant idea. He pitied poor Jeanne having always to eat her grass just plain without any dressing. How much better she would enjoy her food if it were properly mixed into a salad. So Jacques borrowed a big salad-bowl from his mother, and mixed a bundle of grass with oil and vinegar and pepper and salt. He put the bowl before Jeanne, who, being a polite cow, tasted the strange dish. Hardly had her great tongue plunged into the grass than she withdrew it with a melancholy moo, and swinging her tail in an expostulatory manner, she trotted off to the brook to take a long drink of water.

The moral is very trite. “The simple cuisine of nature suits cows better than that of man.”

[Pg 81]

“Every individual, who is not perfectly imbecile and void of understanding, is an epicure in his way; the epicures in boiling potatoes are innumerable. The perfection of all enjoyments depends on the perfection of the faculties of the mind and body; the temperate man is the greatest epicure, and the only true voluptuary.”

Dr. Kitchiner.

Old myths die hard. Nevertheless, as we grow older and wiser and saner and duller, we drop the illusions of our youth, and one by one our cherished beliefs fall from us, argued away by force of circumstance, lack of substantiation, or sheer proof to the contrary.

In this last category we must perforce reckon the excellent Mrs. Hannah Glasse[Pg 82] and her immortal saying, “First catch your hare, then cook it.” Alas and alack, Mrs. Glasse never existed—“there never was no sich person”—and, moreover, the cookery book bearing her name, in none of its many editions, contains the oft-quoted words.

The actual facts, although, indeed, these are open to a certain amount of dubiety, appear to be as follows. In Boswell’s “Johnson” there are several references to one Edward Dilly, who with his brother Charles carried on a flourishing book-shop in the Poultry. Dr. Johnson often dined with these estimable men, and at their table met most of the wits and scholars of the day. The great lexicographer referred to the brothers as his “worthy friends.” It is on record that Edward Dilly, in the presence of Boswell, Mayo, Miss Seward, and the Duke of Bedford’s tutor, the Rev. Mr. Beresford, said to Dr. Johnson, “Mrs. Glasse’s ‘Cookery,’ which is the best, was written by Dr. Hill. Half the trade knows this.”

Now this Dr. John Hill (not Aaron Hill, as assumed by Mr. Waller) was a rather[Pg 83] interesting personality. He was a brilliant man in many directions, who misused his talents, and devoted his energies to so many various professions that it is not surprising to learn that he succeeded permanently in none. It is known of him that he was at different times apothecary, actor, pamphleteer, journalist, novelist, dramatist, herbalist, naturalist, and quack-doctor. He took a degree at St. Andrews, and his nickname was “Dr. Atall.” He married the sister of the then Lord Ranelagh, and by some manner of means got himself decorated with the Swedish order of the Polar Star, on the strength of which he paraded himself as Sir John Hill. No one, however, appears to have taken him at his own appraisement, for he was the general butt of wits, epigrammatists, and lampoonists. His death was attributed to the use of his own gout remedy, and these lines to him still survive:—

Well, this same John Hill, in his earlier[Pg 84] and more obscure days, was doing hack-work for the booksellers, and also following the business of an apothecary in St. Martin’s Lane. This must have been in the year 1744 or 1745. He was struck (as who might not have been) by the ease with which a new cookery book might be compiled by extracting the best recipes from scores of old ones, and rehashing them with original remarks and new settings. He had plenty of material to work upon. The best-known cookery books prior to that date were, according to Dr. Kitchiner (who wrongly dates Mrs. Glasse 1757), Sarah Jackson’s “Cook’s Director,” La Chapelle’s “Modern Cook,” Kidder’s “Receipts,” Harrison’s “Family Cook,” “Adam’s Luxury and Eve’s Cookery,” “The Accomplish’d Housewife,” “Lemery on Food,” Arnaud’s “Alarm to all Persons touching their Health and Lives,” Smith’s “Cookery,” Hall’s “Royal Cookery,” Dr. Salmon’s “Cookery,” “The Compleat Cook,” and many more.

Hill accordingly made up his book, and his introduction was certainly ingenuous and[Pg 85] modest; one phrase will prove this: “If I had not wrote in the high polite style, I hope I shall be forgiven; for my intention is to instruct the lower sort.” The sly dog knew his public, and this is further proved by his not putting his book to the world through a bookseller, but publishing it himself, and evolving an entirely new method of distribution. Among his friends he numbered the ingenious Mrs. Ashburn, or Ashburner, as it is spelt in some of the later editions. This good lady kept a glass and china shop in Fleet Street, hard by Temple Bar, and her customers came from the fashionable squares of Bloomsbury and St. James. Hill made an arrangement with Mrs. Ashburn, whereby she sold his book over her counter and recommended it warmly to all the ladies who called at her shop.

In order to make the illusion of authorship more complete, a female name was wanted for the title page. What could be more simple than “Mrs. Glasse,” seeing that Mrs. Ashburn kept a glass shop? The exact title of the magnum opus ran, “The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy, which[Pg 86] far exceeds anything yet published. By a Lady. Printed for the author and sold at Mrs. Ashburn’s, a china shop, the corner of Fleet Ditch, 1745.” The actual name of Mrs. Glasse did not, however, appear on the title page until the issue of the third edition, for the book was a great success from the first; every one came to Mrs. Ashburn’s to buy it, and its popularity vastly helped the glass and china trade.

About fourteen years ago a lively discussion as to the authentic authorship of Mrs. Glasse filled several columns in the newspapers, the principal correspondents being Mr. W. F. Waller and Mr. G. A. Sala. It was suggested that “first catch your hare” was a misprint for “first case your hare.” Mr. Waller proved that neither of these passages occurred in any known edition of the book, although case, meaning “to skin,” would have been entirely legitimate and in place.

Shakespeare says in “All’s Well That Ends Well”:—

[Pg 87]

And a reference to Beaumont and Fletcher’s “Love’s Pilgrimage” gives the lines—

The actual phrase used is “First cast your hare,” or, in another edition, “Take your hare, and when it is cast.” This simply means flayed or skinned, and was commonly used at the time. The verb “to scotch” or “to scatch” is East Anglian, and has the same meaning. So much for the authenticity of the quotation.

Curiously enough, in the newspaper controversy above referred to, George Augustus Sala strongly supported the claims of Mrs. Glasse herself as the real author, and there certainly appears to be some circumstantial evidence as to a lady of that name who was “habit-maker to the Royal family” about that period, although her connexion with the culinary art is not to be traced. Incidentally Sala mentions a receipt from a cookery book written by “An ingenious Gaul” towards the middle of the seventeenth century, which begins with what he terms “A Culinary Truism,” since changed[Pg 88] into “A proverbial platitude”—namely, the words “pour faire un civet, prenez un lièvre.” This is, however, of course merely a commonplace of the kitchen, and, according to the learned authority of Dr. Thudichum, the imperative of prendre has not the catching meaning apparently attached to it by Sala.