Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

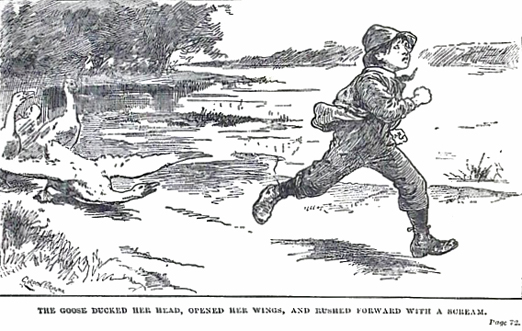

THE GOOSE DUCKED HER HEAD, OPENED HER WINGS,

AND RUSHED FORWARD WITH A SCREAM.

OR

AT THE ELEVENTH HOUR

BY

FLORENCE E. BURCH

AUTHOR OF "JOSH JOBSON," "RAGGED SIMON," ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY GORDON BROWNE

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56 PATERNOSTER ROW AND 65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

CONTENTS.

CHAP.

VIII. "CONSCIENCE MAKES COWARDS OF US ALL"

XIII. THE YOUNG SQUIRE ASSUMES A NEW CHARACTER

FARMER BLUFF'S DOG BLAZER.

IN SEARCH OF A COMPANION.

"I CAN'T see why I shouldn't use my own common sense," said Dick Crozier to himself one fine morning, as he sauntered along the lane. "What else was it given to me for, I should like to know?"

It was a holiday, and Dick had a mind to enjoy himself. Now it happened that Dick's idea of enjoyment on this particular morning did not quite agree with his father's. Before leaving home, Mr. Crozier had given him particular injunctions not to extend his walk beyond the common, and not to go near the river.

"Another time," said he, "I shall have leisure to teach you how to manage a boat. Then I shall not be afraid to trust you; but until then I would rather you kept away."

Dick ventured to argue the point. "Another time," he mightn't have a holiday. His parents had only recently removed into the neighbourhood; and he felt pretty certain that his father would put him to school as soon as ever they got settled in the new place.

"No time like the present," said Dick to himself, as he tried to shake his father's determination. "To-day is my own; no knowing whose to-morrow may be."

But when a wise father has really made up his mind, his determination is not to be shaken.

"You must be content to let me judge what is best for the present," said Mr. Crozier. "When you are older, you will see that I was right."

So Dick had to submit—outwardly, at any rate; and as soon as he had watched his father disappear round the corner towards the railway, away he walked in the opposite direction, grumbling to himself as he went.

It was not a morning for grumbling. The time of year was the end of March. The wind, having made the discovery that all its roar and bluster could not stop the trees and flowers from coming out to meet the spring, had gone to sleep, and left them to enjoy the sunshine till the April showers came on. Birds were singing blithely on the boughs, and even a few humble-bees were to be seen riding through the air with an important buzz, as if they felt that they had got things their own way at last; whilst their working relatives flew hither and thither in quest of honey, with a sharp-toned hum that plainly said—"We must be busy."

Dick heard them, and stopped grumbling. It was too bad to be in an ill-humour whilst everything else—from the kingcups in the hedge to the larks in the sky—was so full of enjoyment. It was not even as if all the ill-humour in the world could alter what his father had said. So he just gave one or two cuts at the hedge with the stick in his hand as a final protest, and began to whistle. A few minutes later he was climbing along a grassy bank, holding by the wooden palings at the top.

There was a plantation on the other side of these palings, and just then a clock in a little tower, with a golden weathercock, struck nine. Dick had heard his father speak of this house as the residence of the Lord of the Manor, so he stopped to have a peep at it through the trees.

It was a large, white stone building, with balconies to the upper windows, supported on twisted pillars, so as to form a shady verandah in front of the lower rooms. A smooth lawn, green as emerald and soft as velvet, sloped up to the gravelled terrace; and behind the house, the grass slanted away to an iron hurdle-fence, within which deer were grazing. Beyond was a little copse, where pines and Scotch firs showed dark against the pale green mist of leaf-buds on the other trees. A gate leading into this copse was painted red; and Dick now noticed that all the gates and railings about the place were of the same unusual colour—which formed a very pretty contrast with the grass.

As he clung to the fence, making these observations, a French window at one end of the verandah opened, and three boys trooped out, followed by a lady, whom Dick took to be their mother. She was young, and very beautiful—or so Dick thought, as she stepped into the sunlight, shading her eyes with one hand, to watch them off; so beautiful that, for the moment, his eyes seem riveted. But only for a moment. The boys no sooner reached the steps than Dick's eyes left her for them. The foremost two bounded down, three or four steps at a time, leaving the third one far behind; and Dick now perceived that the poor fellow went upon crutches, and that upon one sole he wore an iron stand, which raised it full two inches from the ground, whilst the other barely reached so low. In spite of this, he was considerably shorter than his brothers; and Dick immediately concluded that he was the youngest of the three.

"Poor fellow!" said he to himself. "I shouldn't care to be like that. I daresay, though, they're good to him,"' he added, as the others pulled up short and waited for the cripple, who swung himself carefully down, step by step.

But Dick little guessed how hard it is to "be good" to a boy who has to go at a snail's pace, when you yourself have the strength to run and jump. He didn't even notice how the others continually walked a step ahead, nor how the cripple laboured to keep up with them. Neither did he guess how tiring it was to get along so fast. Presently, however, something attracted the attention of the three boys—an early butterfly it must have been. The cripple saw it first, and nodded towards it, and forthwith off the others raced, and left him resting on his crutches watching them. Then Dick understood a little more clearly how hard it was for him; for his brothers entirely forgot him in their wild, mad chase, and he was left alone.

He followed them a minute with his eyes, then turned and looked towards the terrace; but his mother was not even there to wave her hand. She had gone in.

It came into Dick's head to wonder whether the poor fellow could see him there above the fence. He had half a mind to whistle. Dick—with nothing else to do—could very well spare time for half an hour's chat to cheer his loneliness. But just then he remembered who this cripple was, and how presumptuous it might be thought to dream of showing pity for a son of the great man to whom all the land about belonged. And as the other boys, panting and puffing, cap in hand, returned just then, the question was decided once for all. Dick watched them out of sight behind the avenue of trees that led to the lodge, then he jumped down from the bank and went his way, turning now and then to see if they were following.

GRIP AND BLAZER.

A LITTLE further on, the road emerged upon a green; and at the back of this green there was a farm. The house stood back behind the yard, which was hidden from view by tall bushes; and half inside the yard, half outside upon the green, was a pond, where ducks were swimming about in search of dainty bits.

This was the Manor Farm. The man who held it was the Squire's bailiff, Dick had heard his father say. He went up to the gate to look, rather wondering what sort of a thing it was to be bailiff to so great a man, and whether he had any boys.

A shaggy-looking dog, dozing in the sun before his kennel, sprang to his feet with a loud bark as Dick approached, rattling his chain and growling, as if to warn him not to come too near. Finding Dick paid no heed, he jumped up on his kennel and set, up barking so vociferously that another dog behind the house took up the cause. Next minute a servant, wondering what could be amiss, and probably suspecting tramps, opened a side door and came round the corner of the house to look. At the same instant, a man with a pitchfork in his hand appeared from the other corner of the house.

"Hey! Grip, old boy," called he; "what's up? You'll upset the firmament with your row."

Exactly what he meant by this it would be hard to say. He had caught the word up from the Bible, as something made "in the beginning," and therefore very "firm;" so probably it seemed to him the most that any one could do in the upsetting line.

Anyhow, the dog seemed to understand the rebuke. He gave one or two more barks, then jumped down off his kennel with an injured air; and: his colleague of the back premises, finding he was pacified, gave in too, and so the hubbub ceased.

"What was up wi' him?" said the man, coming a pace or two nearer, and resting on his pitchfork. "There's now't amiss, so fur's I can see." For Dick had left the gate, and gone to watch the ducks.

The servant shook her head. "Like his master," returned she; "always kicking up a fuss for nothing in the world. Some folks seem as if they can't be happy else; and quadrupeds is much the same, I s'pose."

"Belike," answered the man, with a laugh. "But if that's so, why, Blazer's the master's dog! My word! I wouldn't like to try his fangs; he'd tear the firmament to shreds."

With this characteristic remark, he shouldered his fork, and, turning on his heel, went back to his work in the rick-yard.

The servant stood a minute at the door looking about her; then she, too, turned and went inside, shutting to the door, but throwing up the window, as if this taste of sunshine had made her long for the free air.

Meanwhile Dick had reached the other gate; for the farmyard had an entrance at each side of the pond, so that carts could come in either way. Here he stopped again; but this time Grip took no notice beyond raising his nose off his paws a second or two and blinking, to show that he was awake; then he composed himself again, or pretended to—just to give the enemy a chance of showing his weak side. But Dick was not to be deceived that way, nor had he any thoughts of invading Master Grip's territory.

After standing still a few minutes, taking observations of the picturesque old house, with its latticed windows and its long, red-tiled, gabled roof, he was just about to go his way, when he was suddenly startled by a most unearthly whoop.

Before he had time to look round, a boy about his own size came full tear into the road a yard or two ahead. "Hullo!" cried he, perceiving Dick.

"Hullo!" responded Dick.

Then they stared at one another.

"Who are you?" asked Dick.

The other burst out laughing. "Who are you?" retorted he.

"Oh! It doesn't matter," answered Dick, a trifle proudly; "only—my father has just moved into the neighbourhood, and I suppose I shall have to get to know the boys; so I thought I might as well begin with you."

The other looked him over well from head to foot. Dick's father was a gentleman, and Dick was dressed accordingly. The other's father was a labourer upon the Manor Farm.

"My name's Dick Crozier," added Dick.

"And mine is Bill the Kicker," returned his new acquaintance.

"That is, your nickname," added Dick.

"Call it what you like; that's all the name I want," said Bill the Kicker in such a final manner that Dick said no more.

"Where do you live?" next asked he.

"Up yonder," answered Bill the Kicker, pointing backward with his thumb. "My father works for Farmer Bluff."

"And mine goes up to town every morning," rejoined Dick. "We live beyond the Manor House, up the hill."

This interchange of confidences was a pretty good basis for an acquaintance, and the two boys were soon engaged in a lively conversation.

"There's a hornets' nest up there," said Bill presently, jerking his thumb in the direction of the field. "I see one goin' in just now. I mean to sell it to the Squire's grandsons," added he, nodding to himself.

"What for?" asked Dick, who was a town-bred boy.

"For sport, of course," answered Bill promptly. "Squires always go in for sport. I reckon we shall have a game."

"Hornets are dangerous, aren't they?" said Dick doubtfully.

"It don't do to get stung," returned Bill; "but then you don't if you can help; and that's what makes the sport. I wonder," added Bill the Kicker, struck with an original thought, "who'd care to storm a flies' nest!—Supposin' that they made 'em, which they don't. And there again, you see," he added further, "flies don't make nests, because they haven't got to keep out of the way—" Which remark contained a wholesome moral, if he had but possessed the wit to see it.

Knowing nothing of such country matters, Dick naturally felt some respect for Bill the Kicker, who talked as if he had it all on good authority.

"Look here," proposed he presently; "tell me when the sport's to be."

Bill shook his head with a doubtful air.

"Why not?" asked Dick.

Bill the Kicker drew his mouth tight, stretching it almost from ear to ear, and shook his head again.

Dick held out a bait.

"I've got a goodish big-sized boat at home," said he persuasively. "I mayn't go near the river yet, but so soon as ever I get leave, I'll let you know."

Bill expressed considerable contempt for the idea of "getting leave;" however, he went so far as to say that when the sport was all arranged, he might see fit to make it known to Dick. "It's the Squire's grandsons, you see," said he importantly. "'Tisn't every one as I could introduce to them."

Dick rather wondered what it mattered whom Bill introduced, so long as it was somebody no lower than himself. But he promised to be in the way as often as he could; and Bill the Kicker, having duly warned him not to drop a word to any one, went off to find the Squire's grandsons and "sell the nest."

FARMER BLUFF.

WHILST Dick was making acquaintance with Bill the Kicker, the Squire's bailiff, Farmer Bluff, was sitting in his parlour, with his leg upon a cushion and a pint mug on the table by his side, swearing inwardly—if not aloud—at the fate which had cursed him with the gout.

Now this fate was none other than the blustering old farmer's own stupidity; for time after time the doctor had warned him that as long as he made that mug his boon companion, so long exactly would his enemy pursue him with its twinging pains.

But Farmer Bluff was obstinate as well as blustering—to every one except the Squire, of course, in whose presence he was like the latter end of March—a lion transformed into a lamb. The excuse he made to himself turned upon the mug, of which he was naturally proud, it being solid silver, an heirloom that his grandfather had left to him. He liked to have it on the table by his side; and if upon the table, why, it must have something in it. And that something must of course be beer, and must be drunk. And so the stupid fellow's gout grew angrier year by year, until at length it got so bad that if he did not swear aloud, it was for no better reason than because nobody was by to hear.

As he sat there by the hearth, looking across his shoulder out of the window at the bright March sunshine that used to call him up and abroad at six o'clock, until this gout got hold of him, he heard Grip set up the furious bark that fetched the servant out to look. Then he heard Blazer take up the challenge; and shortly afterwards the voices of the servant and the man fell on his ear.

Now it was a peculiarity of the old bailiff to resent not being able to hear what passed between other people; so after chafing and fretting for some minutes, he reached out for the handbell that stood beside the silver mug, and rang it lustily. Then he took another pull at the mug, and having poked the fire to a roaring blaze, impatiently awaited the answer to his summons.

This happened exactly at the moment when the servant threw up the kitchen window to let in the air.

"Always kicking up a fuss for nothing in the world," said she again, flouncing back to her washing up, with a strong determination to let him ring a second time. After a minute or two, however, she let drop her dish-clout in the tub, and drying her hands on her apron as she went, hurried off to the parlour.

Farmer Bluff was known to be a bit of a miser, and had few near relatives to leave his money to; and Elspeth had her eye upon a handsome legacy.

"He's over sixty-five," she used to tell herself, by way of comfort when he swore at her; "and gout don't make old bones. I can put up with it a bit longer, on the chance of being mentioned in his will."

But, as it happened, just as Elspeth reached the parlour, there was another ring, this time at the outer door; not so lusty as her master's, though, for all that the bell itself was twice the size.

Filling up a waste space in the hall, there was a cunning china closet, with a narrow window looking through into the porch. A step or two aside and one quick glance revealed who stood without. Going swiftly to the door, Elspeth threw it open with a deferential curtsey. It was the Squire who had given that modest ring; and she never kept the Squire waiting, for he always had a civil word, in spite of his high rank. Then having answered his inquiry as to whether her master was up, she stepped briskly back towards the parlour.

Farmer Bluff was in the act of ringing his handbell a second time.

"A man might die in a fit, for all the haste you make!" exclaimed he with an oath, banging down the bell so violently that the clapper uttered a "twang" of protest. "An indolent, slow-footed hussy!" He was going on with a regular string of abuse, but just as he was in the midst of some words that no proper thinking man had any business to lay his tongue to, the door flew open, and to his great dismay, his eyes met those of no less a personage than the Lord of the Manor.

Farmer Bluff's tirade came to an abrupt termination, and Elspeth having announced, "The Squire, sir," withdrew, leaving her master to put the best face on it.

What with beer, and rage, and shame, the old sinner's countenance was nearly as red as the live coals in the grate. He made desperate efforts to rise as the Squire approached, bearing like a man the torture that would have made him swear like a trooper if Elspeth had been by instead.

The Squire, however, hastened to stop him.

"Keep your seat, Mr. Bluff," said he good-naturedly, as the bailiff blurted out an apology. "Pray don't put yourself to any pain on my account. No; not so near the hearth, thank you," as Farmer Bluff tried to reach a chair. "I'll sit here. The air is mild this morning, and I can see you've been serving your fire to the same sort of rousing as you treat your woman servant to."

The old farmer reddened still more, and mumbled something about "your blood being chilly when you had the gout."

"And you find that swearing makes it circulate," remarked the Squire sarcastically. "Dependence upon others is a very unfortunate condition to come to," added he; "and you have apparently a very inattentive attendant too."

The Squire's caustic tone did not escape Farmer Bluff. He blurted out a few words about "not so bad," only she needed "keeping up to the mark."

"You've chosen a somewhat unscriptural way of setting about it," observed the Squire; "and my experience—the experience of fourscore years—is that whatever is unscriptural is unprofitable, and altogether wrong. Therefore, Mr. Bluff, if I were you I should give it up."

Having uttered this straightforward piece of advice, the Squire dropped the subject, and went on to speak of his bailiff's health.

It was wonderful the contrast there was between the two men. The Squire, brought up all his lifetime in the midst of luxury—had he chosen to live softly—had as elastic a tread as many a man of forty, and looked as hale and hearty as if he had been accustomed to weather wind and storm out in the fields with his own shepherds. His bailiff, nearly twenty years his junior, looked bloated and unhealthy, in spite of his invigorating out-door life about the farm and woods; and half his days, at least, were spent in this arm-chair, with one foot or the other upon a cushion.

There was good reason for the difference; there is for most things, if men only had the sense to find it out. The Squire, from his youth up, had been temperate, using the good gifts of God wisely, not abusing them. His bailiff had never got beyond regarding these gifts as the wages which it was his good fortune to earn from the Squire; and he had gone to work with the intention of getting the greatest possible amount of enjoyment out of this little bite off the great man's luxury. Thus, grasping all, he had come pretty near losing all; for, ask anybody who has made close acquaintance with gout, and they will tell you that there is next to no enjoyment in life for those who have made it their companion.

The moral is,—avoid intemperance, remembering always that beer is not the only thing that may be abused, and that gout is not the only punishment; for, sad to say, there are as many sins as there are weeds in this fair world, and a punishment to each. As the Bible has it—in a form that no one need forget—"Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap."

Sow sins, and you shall reap punishment as surely as did Farmer Bluff.

This was the sum and substance of the Squire's thoughts as he sat down on the window-seat. "I'm thankful I shall go down to my grave without gout," said he to himself, as he watched the contortions of his bailiff's features; for it was vain for Farmer Bluff to think of not making faces. He had put his foot to unusual inconvenience in his attempts to show respect; and it cost effort enough to refrain from bellowing aloud at the pain.

"I hoped to find you better than this, Mr. Bluff," began the Squire after a pause, putting his gold-headed cane between his knees, and crossing his hands over it. "This has been a long attack."

"It has, sir; a—very long attack."

Farmer Bluff usually hesitated a good deal in talking to the Squire; otherwise he might have let slip unsuitable expressions, such as he was in the habit of using to Elspeth.

"The longest you ever had, eh?"

The Squire did not want to be unkind, but he had called in with the intention of saying something rather disagreeable; and it had got to be said, in spite of his natural inclination to say pleasant things.

"By far the longest," repeated he.

Farmer Bluff declared himself heartily tired of it, adding in an injured way that no one knew what suffering was until they had tried gout.

The Squire shook his head. A man has no right to feel hardly done by when he deliberately chooses to bring pain upon himself. "I'm heartily tired of it, too," said he; "and the fact is, Bluff, I'm getting too far into years to be my own bailiff—and that's what it comes to nowadays. For these keepers and labourers of yours—well! I've no doubt you give your orders. A man might give his orders in the other hemisphere by telegram. But if I didn't go round and see to things for myself, they would be in a pretty muddle. Why! I was in the saddle at half-past six this morning to do your work. A glorious morning it was too; as glorious as God ever made. Time Was when I'd as soon have been out myself as trouble you—except for the sense that a man with abundance of this world's goods is bound to broadcast some of his money amongst dependants. But an octogenarian begins to need a little indulgence, or he will do very shortly, for the time must come to all of us, Mr. Bluff."

"Ay, that it must, sir," acquiesced the bailiff meekly, feeling rather as if his time had come; for he could see pretty plainly what the Squire was driving at.

"I should not like," continued the old gentleman after a pause, "to leave the estate out of working gear when I go. It is not as if I left a grown man in my place. My grandson is such a mere child that I can hardly hope even to see him attain his majority; and that is what I came to speak to you about. You have served me many years, Bluff; but the fact is, you are not what you were, and I feel that I ought to see a competent man in your place, whilst I myself am still competent."

Farmer Bluff began to whine. Long service deserved indulgence, he hinted. "A man must take what the Lord sends him," said he.

But the Squire stopped him. "Men often make mistakes about the source of their misfortunes, Bluff," said he. "I don't believe that your complaint is often of the Lord's sending."

The bailiff's eyes reverted uncomfortably to the silver mug. He knew very well what his patron referred to.

"I might very easily have put myself in the way of it," continued the Squire. "My father left me a well-stocked cellar, and I have had to dispense hospitality; but I have mostly contented myself with listening to other people's praises of my wines, remembering an old saying that those who constantly seek their own reflections at the bottom of their tankards are likely oftenest to see an ass. The saying certainly holds good of a man who, in immediate opposition to his doctor's orders, feeds his gout on beer. No, Bluff: if the Almighty were responsible for your gout, I should feel very differently about the matter. As it is, although I shall consider myself bound to see that your old age does not come to want, you must certainly understand that you will have to make way, within due notice, for a man who can put his beer mug on one side in favour of duty."

Farmer Bluff tried hard to obtain a commutation of this sentence.

But the Squire was a man who knew his own mind, once it was made up, and who did not make it up hastily either. He had for some years past been much disgusted with his bailiff conduct; and the experience of the last few months had finally decided him. He was determined to leave upon the estate a thoroughly efficient bailiff. To this intent, having given due notice to the gouty old rascal who at present held the office, he now rose and took his leave, Farmer Bluff ringing his handbell— though not so roughly as before—for Elspeth to show the Squire out.

THE SQUIRE'S GRANDSONS.

WHILST the Squire had been giving old Bluff his deserts in the farm parlour, his three grandsons—none other than the boys whose mother Dick had thought so beautiful—had left the grounds by a winding path that skirted the plantation and emerged on to a fieldway leading into the road a few hundred yards above the farm. Turning to the left hand of the farm, this road ran round the foot of a piece of rising ground. Probably the man who first made a cart-track there, found it pay better to go a little way round than to make his beasts drag their burdens over the hill. But there was a shorter cut for pedestrians almost opposite the pathway from the Manor House; and for this the boys were bound.

Just as they were in the act of crossing the stile, who should come round the bend but the Squire, whose next business took him up that very road. The boys saw him at once. Two of them—the two taller ones—ran forward to meet him, the other following at his quickest pace. The Squire was a favourite with his grandsons. He was such a boy amongst them, although he had been born over eighty years before them; and yet withal he was so grand and courtly.

Will and Sigismund dashed forward, but the Squire looked beyond them to the cripple, who was exerting himself manfully to show equal appreciation of his aged relative.

"Bravo, Hal, bravo!" cried he, applauding with his gold-headed cane.

Will and Sigismund faced about, looking half-ashamed, as if they felt it was almost mean to have taken such an advantage of their afflicted brother. But the Squire did not exactly intend that. It would have been altogether too hard for boys with strong legs to give up using them because their brother limped on irons. It was rather that the Squire had a very tender spot in his heart for Hal, and that he saw in the boy's brave, invincible spirit an earnest of what the man would be.

"God grant that he may grow to be a man!" he often uttered in his heart. And it really seemed that Hal was growing stronger year by year.

Meanwhile Hal, flushed and out of breath, was up with them.

"Where are you going, grandfather?" asked he eagerly, as he swung himself round to walk by the Squire's side, Sigismund making way for him.

"Up to the cottages by the wood gate," replied his grandfather, laying one hand on his shoulder. "Almost out of bounds for you, eh?"

But Hal shook his head. "Why, I've been right into the wood, you know; last autumn, nutting."

"Ah, to be sure!" acquiesced the old gentleman.

"But what are you going there for, grandfather?" questioned Hal, who was noted for his inquisitive spirit. Impertinent, some good people would have said; but not so his grandfather.

"How can a boy learn what he doesn't know, if he may not ask a question?" he would say. "A spirit of inquiry is one of the first requisites to learning." So now he answered without reserve.

"To see about having one put in repair for Farmer Bluff," said he.

"For Farmer Bluff?"

The question was from all three at once.

The Squire nodded gravely. "For Farmer Bluff," repeated he. "He has to leave the Manor Farm."

"To leave?"

"Why, grandfather?"

This was Hal's question. Hal always came straight to the point, as if he had a right to know; and his grandfather seldom, if ever, put him off.

"Because," answered he, "the time has arrived when he must make way for a better man."

"But surely, grandfather," said Hal, "you won't turn him away, after all the years he has been bailiff. Why! Ever since mother first brought us to live with you."

"Ay, and before that," broke in the Squire regretfully. "When I thought your poor father would have been Squire after me. Twenty-seven years Farmer Bluff has lived on that farm; but—"

"But it isn't fair to turn him out because he's getting old, grandfather," interrupted Hal, with a bold familiarity that no one else would have dared to use towards the old gentleman.

"Tut, tut, lad," rejoined the Squire. "Who said was because he was too old?"

"Well, grandfather," put in Sigismund, who according to size would be the next youngest to Hal, "you said 'a better man.'"

"Better doesn't always mean younger," said Hal eagerly; "does it, grandfather?"

"Nor does younger mean better," returned the Squire. "I always like to think of my eighty-four years as a token of God's favour."

"Good people generally live to be old, don't they?" suggested Sigismund, straying from the point at issue. "In the Bible they did."

"Steady living is conducive to longevity;" replied the old man. "That is to say, those who live sober, temperate lives give their constitutions the fairest chance of withstanding natural decay, and of escaping the ravages of disease by which so many are prematurely cut off."

"Is that why Farmer Bluff has the gout?" queried Hal. "Because he has been intemperate?"

"Very likely," replied the Squire. "It is quite certain that at the present time he is aggravating the complaint and forfeiting my esteem by the childish obstinacy with which he persists in drinking beer, when he knows it is as good as drinking so many pains and twinges. But you mustn't run away with the notion that God always rewards virtue with long life; for that is not His greatest gift."

Hal asked no more questions just then. They had crossed the stile during this conversation, and were climbing the pathway up the hill towards the wood, where there was plenty to claim the attention of boys.

Larks were rising from the tussocks; finches darted in and out the hedge; and as they got nearer to the wood, wild rabbits, all tail, frisked about their burrows. Once or twice a grey rat ran out of his hole, and sat upon his haunches in the track, staring stupidly before him until they were quite close; then doubling suddenly, and disappearing in the ditch.

Will and Sigismund were full of excitement, running and jumping and leaping; but Hal kept by his grandfather, swinging himself along at an even pace that agreed very well with the old gentleman's step; and so they reached the gate of the wood, and the cottages in one of which the Squire intended his bailiff to live rent free.

There was already a noise of carpenters at work, and a cheery sound of men talking over their saws and planes. Hal followed his grandfather inside, and went round, listening with great interest to all that passed between him and the workmen. But the other boys stayed outside, overrunning the garden, and talking to the gamekeeper, who lived next door. Finally they strayed into the wood, which was only separated from the garden by a ditch, dry summer and winter alike. By the time the Squire had finished giving his orders, they were quite out of sight and hearing.

At length, the Squire sent the keeper down the clearing after them. Hal was standing by his side, resting on his crutches. The Squire, looking down at him, saw that his face wore a thoughtful look, and fancied he was tired.

"Better go inside and sit down on Champion's sawstool," suggested he kindly; "it's a long way back, and you and I aren't so young as those two madcaps. Eh?"

At that instant, however, Will and Sigismund appeared, talking gaily to the man as they advanced.

The Squire beckoned, and they set forward at a run, giving the stout old Velveteens a good view of their soles, and leaving him to follow at his sober pleasure. But Hal had already seized his opportunity.

"Grandfather," said he, moving nearer.

The old man faced about.

"Grandfather, I was wondering if I could make Farmer Bluff see how silly it is to keep on having gout?"

"To keep on drinking beer?—Hardly," quoth the Squire, "since his doctor fails. People usually believe their medical man, if anybody, when they are in pain."

"And I mean," added Hal, anxious to gain his point before the others came up, "if he left off having gout, should you still be obliged to turn him out of the Manor Farm?"

"Why, no," answered the Squire; "not if he showed himself capable of doing his duty as bailiff of the estate. But the fact is, I can't be Squire and bailiff too at my age; and if I could, I shouldn't long be able to, because—things don't go on for ever and a day, Hal."

Just then the other two boys cleared the ditch, and bounded up, with a ready apology for having kept their grandfather waiting; then, passing in at the back door, they all went through to the road again.

On reaching the front door, the Squire suddenly remembered something he had meant to say, and stepped back again. Hal waited with him, but Will and Sigismund ran straight out.

In the middle of the road a boy was standing, looking this way and that, as if undecided in which direction to go. Seeing two lads his own age, he at once advanced.

"Can you tell me where I am?" asked he.

"By the gate of the wood," answered Will, pointing past the cottages to the red-painted gate.

"Is this beyond the common?" asked the boy.

"Most certainly," was Will's reply.

"Then I'm where I've no business," rejoined the boy, who was none other than Dick Crozier. On leaving his new acquaintance, Bill the Kicker, he had wandered on by the right-hand road, until his way had met that of the Squire and his grandsons by the cottages.

Apart from Hal, Dick did not recognise them as the Manor House boys. Hal no sooner appeared in the doorway, however, than their identity flashed upon him. The next minute, the Squire himself emerged, tapping the ground briskly with his cane as he walked, as an indication that time was short and they must get forward without delay.

Perceiving Will in conversation with a strange boy, he stopped short; whereupon Will explain that Dick had lost his way.

The Squire inquired where he came from, but this Will had not yet asked; so the Squire turned to Dick himself.

"Your name, my boy?" asked he.

Dick had no sooner recognised Hal than it flashed upon him that the grand old gentleman with the gold-headed cane was none other than the Squire himself; and although not more troubled with bashfulness than most boys of his age, he was just a trifle flustered at the discovery. Nevertheless, he answered straightforwardly enough,—

"Crozier, sir."

"Crozier; a son of my new tenant, surely?" said the Squire in his courtly way. "I am always pleased to make the acquaintance of a tenant, Master—"

"Dick, sir."

"Master Dick; and as we're all going one way, we will proceed together, if you please."

So they set off, Dick and Hal walking on either side of the Squire, the other two a pace or two in front.

"WHATEVER IS, IS RIGHT."

BEING Easter holidays, and the tutor who superintended studies at the Manor House having gone North to visit his friends, Hal and his brothers had things pretty much their own way from sunrise to bedtime. They walked; they played games; they followed their grandfather about; they rode the donkey about the field—or rather Will and Sigismund did, whilst Hal looked on and clapped his hands.

In short, they did all that boys in holiday-time try to do; they took every possible means to make the best of their freedom. All things considered, too, they were very good to Hal, who—hard as he tried to keep up with them—was rather a clog with his crutches and his irons.

On the morning after the Squire's interview with his bailiff, however, Hal evolved a scheme which relieved them of this clog.

One of the men had let loose a ferret in the granary, to hunt the rats, which of late had been committing great depredations in the henhouses. For some time the boys had been too excited to notice their brother's sudden disappearance. But presently, the hunt drifted upstairs into the loft overhead. This at once recalled Hal to mind, because he could not very well climb a ladder without assistance.

"Where can he have got to?" exclaimed Sigismund, who had been outside to look about for him.

Somehow Sigismund, being of a more unselfish disposition, was always the one to wait behind for Hal.

"Gone indoors, I expect," returned Will, already half-way up.

Hal had a way of "going indoors" when he found the game beyond him. "It's no fun when you ache," he would say; "and it doesn't make you a bit worth playing with." And he would be found afterwards, deep in a book—not always a story-book either.

Meanwhile, Hal, having slipped out through the stable-yard and gained the road, was on his way to the Manor Farm, meditating on the unaccustomed rôle which he had taken on himself.

About the same time, Dick Crozier, intending to hang about the farm, on the chance of catching Bill and hearing something of the hornets' nest, had chosen that direction for his morning's stroll. Recognising the wooden tap-tap of Hal's crutches on the gravel as he hurried down the hill, Dick determined first to renew acquaintance with the Squire's grandson; so he slackened pace, and the boys met at the lodge gate.

Hal at once nodded pleasantly; and Dick, returning the nod, joined him without further ceremony.

"You get along jolly fast, considering," remarked Dick pleasantly, as the conversation turned on walking. "That's hard work, though, I should say."

Hal nodded, and went a little faster, breathing short with the effort.

"Was it an accident?" inquired Dick; "or were you born so?"

"It came on when I began to walk," answered Hal; "at least, so I'm told. Of course, I don't remember being any different."

He didn't seem to mind talking about it, which Dick thought very sensible. "Where would be the use of minding?" said he to himself. "It wouldn't alter the fact." He little knew the effort it cost Hal to put his injured pride on one side.

"What are the irons for?" asked Dick next.

"To stretch this leg," answered Hal, nodding to the right. "That one was the worst; and the sinews shrank—just like a wet string. It's pulled out tight all the while, to try and stretch it longer."

"Don't it make it ache?" asked Dick.

"Sometimes," assented Hal.

He might with truth have said, "most of the time;" but Hal was a bit of a hero in his way. "I'm used to it, you see," he added patiently.

"I shouldn't like to be like that," said Dick.

"Nobody would, of course," returned Hal; "but when you are, you've got to make the best of it. You think of all the great men you've ever read about, and wonder how they'd have borne it; and that helps you."

Dick was so much struck by this way of looking at a misfortune, that for several minutes he was silent; and Hal's crutches went on tapping out their melancholy tale upon the road; step by step, step by step, patiently—the only way to rise superior to a misfortune of that kind.

"Who is the greatest man you ever read about?" asked Dick presently.

Hal assumed a thoughtful air. "That's rather hard to say," answered he; "because some are great for one thing, some for another. It's like that with plants, too, you know. There's corn, and there are potatoes; and we couldn't very well do without either. I shouldn't like to do without apples, nor green peas—we always have them sooner than other people; (forced, you know;) and I'll ask grandfather to send you some. Then again," he ran on, before Dick had time to thank him for this promise, "there are flowers—more beautiful than useful, as we count use. It's just like that with men, I think."

Dick could not jump quite the length of this argument. He suggested Robinson Crusoe.

But Hal's estimate of greatness differed from Dick's. "Crusoe was pretty well in some things, considering how he began," said he. "He was shifty, but he wasn't all round; besides, he was an awful coward, and he swore. And then, he's only in a book. Now Socrates—only he was a heathen—he died bravely when they made him choose between the dagger and the poison cup. And Napoleon—he made himself a king out of a common soldier, and he must have been a great man, or people wouldn't have given in to him; but then he did it all for the sake of power, and he wasn't good.

"A man's motives go for a great deal, you know. Then there were the martyrs; I like them. They had their bodies broken on the wheel because they wouldn't tell lies. I often think of that, because it was something like having my leg stretched, only thousand times worse. There was Shakespeare too. He wrote very fine plays. That was more like being a flower, I should say; and I don't know that he was particularly good, or that he did anything else worth doing. And there was Sir Isaac Newton, who discovered why apples fall done instead of up. He was very learned, of course. But I like men such as Wilberforce and Clarkson, who did so much to abolish slavery; or Moffat, the missionary; or Howard, who went into a lot of gaols, and made a fuss about having them kept cleaner, and the prisoners better treated. In my opinion," added Hal, "they were some of the greatest men that ever lived—except Jesus Christ."

Dick had not read about any of these heroes. He said that he should like to.

"Of course," continued Hal; "none of them come near Jesus Christ. You don't expect that. There was Buddha. A missionary once told me about him; and I've read since. He was a prince in India; and he gave up everything to try and find out how to make people happier, because one day when he went outside the palace, he discovered that everybody wasn't so well off as himself, and that people had to be ill and die. But he didn't end up the same as Jesus Christ," Hal concluded. "And then it's such an immense while ago that I don't think it's very easy to be sure whether it's all true."

Hal was fond of books, and had an original way of talking about what he read.

"I don't suppose that any of them went on crutches," suggested Dick.

Hal thought not. "One of them was lame," said he. "His name was Epictetus; he was an eminent philosopher. It was through his master's cruelty; and that was very hard to bear. But crutches don't matter to some sorts of greatness," added he. "You wouldn't get along very well on crutches if you wanted to fight; and fighting isn't always wrong either, though I don't like it. Where you do it to put down injustice, for instance, or to help the weaker side, it's noble and right."

"Or if you do it to defend your wife and children," put in Dick.

"There were some great men deformed," continued Hal. "There was Pope. He had to be laced up in a pair of tight stays to keep him from doubling up; he used to sit up in bed and write poetry. I've read some of it, and it's very fine. 'Whatever is, is right,' comes from Pope; and though you can't say that of everything, there is a sense in which it is very true. But Pope wasn't brave always. He used to be very disagreeable to his servant when he was in pain; and I think if any one was really great, they would rise superior to affliction, and not make other people feel it. You see," added Hal, in a tone of reflection, "it's bad enough for one person to go on crutches, without making all the rest miserable."

"You mean to be great, I suppose," observed Dick admiringly. "What shall you be?"

Hal reflected. "That's difficult to say exactly," said he. "Of course I've got to be the Lord of the Manor."

"You have?" interrupted Dick. "I thought it was your tallest brother."

"Will?—No; it's always the eldest son. I'm the eldest," added Hal, just a trifle proudly.

Dick was astonished. He had made up his mind from the very first, that Hal was the youngest of the three.

"You see, I'm short," said Hal simply. "It makes you grow slowly when you're like this."

"That's a pity," said Dick, knowing of nothing better to say.

"Yes; I suppose it is," said Hal; "only—'Whatever is, is right,' unless, of course, it is something contrary to God's will; and this can't be, as I was born so. I mean all the same to be like my grandfather."

"He isn't very big," put in Dick, cheerfully.

"Some people," continued Hal, "don't think you can be a proper Squire unless you can ride in the steeplechase and follow the hounds. My grandfather doesn't now; but he used to formerly. I've heard him say what a pity it was that I couldn't learn to sit a horse. But you see it isn't just the same as it used to be in the olden times when there were serfs, and the lord of the manor lived in a castle with a moat and drawbridge. He had to be a sort of petty king in those days. And if other lords stole his vassals' sheep or wives, he had to rally all his men and besiege their castles. I'm afraid I shouldn't be very well able to do that. But all that is changed nowadays, and there are no serfs—which ought to make the poor people much better off. What a good Squire has to do is to pull down all the badly built cottages on his estate, and have them properly drained, and damp courses put in, so that the walls don't rot."

Dick inquired whether that was the reason why some cottages near his father's house were being pulled down.

Hal nodded. "Why," said he, "the jam actually mildewed in the parlour cupboard! Think of that I saw it. And the old lady's wedding-dress went all spotty where it hung in the press upstairs. It was silk; and she had worn it every Christmas Day and Easter Sunday since she was married, and every time any of her sons and daughters had a wedding. It was very vexatious for her. You couldn't let such a house stand."

Hal spoke with such earnestness that Dick was quite convinced, and immediately thought of the preservation of old silk wedding-dresses as one of the chief duties of a good Squire.

"There's to be a proper slate course at the bottom of the walls this time," added Hal. "You'll see it will be quite dry."

"Then there's the drainage," continued he; "because if that's bad, the wells get poisoned, and people have fevers. And although it doesn't say anything in the Bible actually about drainage, it says a great deal which seems to me to mean that if you own an estate, you ought to look after the health and comfort of the tenants. Oh, there's a lot a Squire has to do that I think I could do! And perhaps," he added thoughtfully, "I should do it all the better for not riding in the steeplechase and following the hounds. You can't do everything; and if you come to think," concluded Hal, "perhaps that is why God let me be like this; because, you know, He could have made it different if He had chosen to."

"A Squire has to make a speech at the rent dinner, doesn't he?" suggested Dick, glad to show that he had some knowledge of a Squire's duties.

"Oh! I think I could manage that all right," returned Hal, "when I got to be of age. It wouldn't be noticed that I was like this when I stood up behind the table; so I shouldn't feel bashful about it. Besides, I don't think I should mind when once I was Squire, because people would respect me; and I should try to show them how great men bear such things."

Dick thought this a very plucky way of looking forward to such a terrible ordeal.

"Another thing you have to do," said Hal, as they arrived at the gate of the Manor Farm, "is to see that the bailiff and other people about the estate do their duty. And if they don't—through drink or laziness, you know—you have to turn them out, and hire somebody who does. But I'm going in here," added he, breaking off abruptly.

Dick was sorry, for he found Hal's company both instructive and entertaining; moreover, his vanity was rather flattered by this acquaintance with the future Squire. But fortunately Hal appreciated a good listener.

"Where shall you be when I come out?" asked he, resting on his crutches to open the gate; "because I like somebody to talk to."

Dick, having nothing particular in view, readily promised to wait about until Hal came out; and having watched him past Grip—who only rose to his feet in a respectful sort of way, and walked quietly forward the length of his chain—he sauntered slowly on.

THE YOUNG SQUIRE.

ON going, as usual, before answering the doorbell, to peep through the little window in the china closet, Elspeth was not a little surprised; for there, on the seat in the porch, his crutches on either side of him, sat the young Squire, resting.

He was examining a leaf-bud on a tendril of the honeysuckle when she first caught sight of him; but directly the door opened, he got to his feet, inquiring for Farmer Bluff.

Elspeth at once invited him to enter. "A message from the Squire, sir?" asked she, as she closed the door behind him.

Elspeth knew all about the nature of the Squire's business with her master on the previous morning, for the old sinner, in his rage and vexation, had drunk more beer than ever, and had used more bad language than enough about it, whenever she had had occasion to go near him. She was not sure, moreover, how his dismissal would affect her own prospects, for he would be in receipt of less money; and ill as he could do without her help, in his frequently crippled condition, it was very doubtful whether the miserly old fellow would choose to draw upon his hoard in order to pay her the usual wages.

In that case, much as Elspeth disliked the idea of breaking away from the old place, she was determined to seek her fortune elsewhere; for it need hardly be said that Farmer Bluff was not the sort of master to win the affection of a dependant.

"For money," and not "for love," had been Elspeth's rule of service. Having, however, one or two cronies in the neighbourhood, from whom she did not care to part, she was fain to entertain a half hope that Hal might have been sent round to negotiate a compromise.

But Hal was not disposed to divulge the purpose of his visit.

"I want to see Farmer Bluff, if you please," said he, "if he's up. If not, perhaps you could take me to his room. I daresay he wouldn't mind."

Farmer Bluff was up, though, as Elspeth promptly informed the young gentleman; and, stepping to the parlour door, she flung it open, announcing, "The young Squire, sir."

Farmer Bluff, as it happened, was in a brown study, leaning forward on the elbows of his chair, with his eyes fixed on the fire. Not catching the first two words of Elspeth's announcement, he looked up with a start, expecting to see his master come to torment him again. His relief can best be imagined when, instead of meeting the penetrating gaze of the Squire, his eye fell upon the slight form of Hal, with his frank, boyish face all abeam to greet him, as he swung himself across the room.

"Good morning, Mr. Bluff," said he pleasantly. "I'm glad to find you up. You ought to be out this fine weather. You're missing ever so much, so I thought I'd come and have a chat with you about it."

"And make me want all the more to be out," said the old farmer, doing his best to assume a pleasant manner. But his thoughts, ever since Elspeth landed him in that chair, had been of such la disagreeable nature, that he found it quite impossible, all in a minute, to shake the growl out of his tone.

"I'm glad my legs don't prevent me getting out," said Hal, contemplating the bandaged limb with compassion, as he seated himself opposite, and lodged his crutches against his chair.

"You're not of a gouty age yet, young master," returned Farmer Bluff. "It'd be sorry work to have it at your time of life."

"It isn't everybody has it when they're old," said Hal. "My grandfather doesn't. I don't think I shall."

"Maybe not," returned Farmer Bluff. "'One thing at a time' is the saying. You've got your share in the way of legs."

"But I mean," explained Hal, determined to make this the thin end of his wedge; "I mean that I shall take care not to have it."

Bluff laughed—a cynical sort of laugh.

"You'll have to take pretty much what comes," croaked he.

"But some things don't come," said Hal.

"You don't send for 'em," returned the bailiff, with another laugh. "That's very certain; not such things as gout."

"Don't you?" said Hal. "It seems to me you do. Beer makes gout, doesn't it? You're always drinking beer."

The bailiff involuntarily reached out for his mug; but it was empty—which went to prove the truth of what Hal said. Farmer Bluff drank beer so often that he hardly knew when he did it.

"It may be partly owing to that mug," continued Hal, after a few minutes' consideration. "You're rather proud of it, you see. I think that's natural. But, do you know, if I had a mug that made me have the gout, I'd send it to the smith's to be melted down and made into something else. Let me see—you might have it converted into a silver inkhorn, like my grandfather's. You couldn't drink out of that."

"That's certain," returned the bailiff, amused in spite of himself.

"Well, will you think about it?" said Hal. "Because that's what I came about. You see, if you go on having gout, you can't go on being bailiff. My grandfather says so. It's one or the other; and it's quite fair, if you come to look at it. You're no bailiff if you have to sit with your leg up on a cushion all day like that; because you ought to be out and about the estate, seeing after things. And if it's your own fault that you can't, why, there's no doubt about it's being just; is there?"

Farmer Bluff shifted on his chair. He knew Hal was quite right. And Hal had brought out his arguments very warily too. First, that the gout was of the old fellow's own seeking; second, that being gouty, he couldn't attend to his business, and had clearly no right to be bailiff; and third, that this being so, he stood self-condemned, and could in nowise complain if the Squire turned him out.

Hal knew this very well, and was not surprised at getting no answer to his question. "I think I'll go now," said he, taking his crutches. "It's a beautiful morning. I wish you could be out of doors."

Farmer Bluff reached out for the bell, but Hal stopped him. "You needn't ring for the servant," said he. "I can get out all right by myself; and I daresay she's busy. When you have to wait on any one who can't move much, I should think it gives you a lot to do."

So the old farmer left the bell alone.

"I'm very much obliged to you for looking in, Master Hal," said he, as the boy did not attempt to go.

"I'll come again," said he, "if you like it. There's one thing more I was thinking. It's in the Bible. 'Thou hast destroyed thyself.' I don't remember who it was, but I've got the words in my head somehow. It's a pity to destroy yourself, isn't it?—Because there are so many ways that you can't help, of getting destroyed."

Farmer Bluff shifted again; and Hal, resting on his crutches, looked as if he very much wished he knew how to go on. But it was rather difficult, especially when the old fellow didn't make any reply.

At length, he put his right crutch forward, preparatory to moving on. "Well, good morning, Mr. Bluff," said he. "Don't forget about the mug; and I hope your gout will be better. I should like you to go on being bailiff when I'm Squire, because I'm used to you, and strangers aren't so nice. Good morning."

And away went the crutches across the floor, with their measured tap, tap, whilst the old bailiff sat looking after him with an astonished expression on his face; and when Hal, halting to turn the door-handle, gave him a last bright nod, he nodded too, twice or thrice. Then he twisted himself round in his chair, to watch the boy across the yard. But Hal went first to pay his respects to Grip, and peep round the corner of the house at Blazer. Catching sight of the old man through the window as he passed, however, he approached and put his face close to the glass.

"Don't forget the mug!" called he.

Whereupon Farmer Bluff, too much astonished even to nod, took the empty heirloom in his hand, turning it over and over, and falling back again into a brown study.

Out in the road again, Hal looked about for Dick. But he was nowhere to be seen. Dick was one of those people who find time hang very heavy when they have to wait; and seeking temporary diversion, he had completely forgotten his appointment with Hal.

Just past the farmyard was a pathway over the fields, behind the orchard and back premises; and having perched himself upon the stile to wait, it occurred to Dick to wonder where it led to. No sooner wondered than both Dick's legs were over the top-rail, and, jumping down, he started off to see for himself, whistling as he went.

Now, these back premises were Blazer's especial charge; and such a vigilant sentinel was Blazer, that he no sooner heard the sound of Dick's whistle than he was up in arms.

Dick came to a halt, remembering the character he had heard of the beast from Bill the Kicker's father. But at that very moment, who should appear from behind the orchard but Bill himself.

"Hullo!" called he.

Whereupon Blazer barked more furiously than ever.

Blazer had his own reasons for mistrusting the sound of Bill the Kicker's voice.

"Ain't he sharp!" said Bill. "He smells you out if you creep by ever so quiet."

Dick nodded. "What about the hornets' nest?" asked he eagerly.

But Bill put him off with a half answer. The fact was he had been in too much of a hurry in proclaiming it a nest, and it had turned out to be no such thing.

Meanwhile, Blazer had not ceased barking.

"Rather a dangerous animal, isn't he?" suggested Dick.

"I shouldn't care to meet him out for a walk," returned Bill.

"Is he near the hedge?" asked Dick.

"Agen' the back door," answered Bill. "You ain't afraid of him?" added he, with a grin.

"Why, no," said Dick, ashamed to own the contrary. "Lots of people go this way, I expect."

"In course," returned Bill; "else what's the pathway for? Nobody takes any notice of Blazer. My eye, though, ain't he wild if you get through the hedge!"

Dick inquired if Bill was ever guilty of such a thing.

Bill answered by a mysterious nod and the word "apples," accompanied by a jerk of his thumb towards the orchard. "You have to look out when there's nobody about, though," said he; "else he'd bring 'em out like a shot with his row. To see him, you'd think he'd break his chain."

"It's too strong I should think," said Dick, with a feeling, however, that it would be preferable to go without the apples rather than risk meeting Blazer off the chain.

"He got loose the other day, though," returned Bill. "Killed a goose, and made old Bluff so mad. Old Bluff always reckons to get a lot by his geese; and now there's a whole setting spoilt. Thirteen short for market next Christmas," added Bill knowingly.

Dick knew nothing about geese. He made numerous inquiries concerning their nesting and hatching, all of which country-bred Bill was able to answer in detail.

"They lay pretty big eggs I should think," said Dick, recollecting an ostrich egg which he had seen in a South African uncle's cabinet.

"Oh don't they!" responded Bill. "A dinner and a half for a chap. I often help myself when there's no one about."

Dick, instead of being shocked, looked rather envious of Bill's experience.

"I daresay I could get you one," hinted Bill obligingly. "They're worth a shilling each; but as it won't cost me nothing but the trouble, I'll say sixpence to you."

Dick thought that a good deal. Sixpences were not very handy in finding their way to his pockets for his father was by no means rich. The prospect was tempting, however; and not knowing that the sum named was full double the ordinary market price, he at once closed with the offer.

"When am I to have it?" asked he eagerly.

But this Bill was not prepared to say. It depended on so many things; on Blazer, on Elspeth, on his father, and on the geese. So Dick must needs be content with a conditional promise that at some time or other, within the shortest possible limit, he should be in possession of the coveted delicacy.

THE SHORTEST CUT.

BILL the Kicker had his own reasons for wanting sixpence.

A few days since, being very hard up for a pocket-knife, he had watched an opportunity to abstract the necessary amount from his mother's rent-money; and he was anxious to replace it before the theft was discovered.

This rent-money was the proceeds of his mother's exertions with her mangle, and was always dropped into an old tea-pot occupying a place of honour on the mantel-shelf—each amount put in or taken out being duly entered in red pencil on a square of card, which also had its quarters in this Britannia-metal safe.

Now it always fell to Bill's lot to carry the mangling home out of school hours; and it seemed to him, when he got the idea of taking the sixpence, that it was nothing but fair he should have something for his pains.

"If other people don't pay you, why, you must pay yourself," reasoned Bill. "That's square enough."

When he came to see the red pencil entries on the card, he was somewhat shaken as to the safety of this policy, however "fair and square" it might be. It was not even as if he had been one of many brothers. The coin would certainly be missed; and upon whom but himself should suspicion fall?

It occurred to him to make the experiment of rubbing out one of the entries. He had no eraser, but he was pretty ready with expedients. Quick as lightning, one finger went to his mouth, and thence to the tidily kept account; but such a horrible smear was the result, that his hair almost stood on end. It was impossible but that his mother would see that the card had been tampered with; if, in addition, she found the money sixpence short, the mischief would be out, and he would be "in for it."

Exactly what that might mean was not clear to Bill. All he knew was that his father had given him the strap on one occasion, and that he did not desire a repetition of the experience. It was already Thursday. Under ordinary circumstances, the sixpence would have had to be replaced before Monday. But since Farmer Bluff had been laid up, the rents had been running; so that, unless the Squire suddenly took it into his head to send some one round, there would be no particular hurry.

Bill, however, was shrewd enough to believe in being on the safe side. Accordingly, he had left no stone unturned to put himself in a position to restore the stolen sixpence. The scheme about the hornets' nest having fallen through, he had even hunted up and down outside the shop fronts in the street, in hopes of picking up change dropped by some careless housewife when out marketing. But, fortunately for the good of thieves, they do not often receive such encouragement in their crooked ways; and Bill's researches proved fruitless.

He was still puzzling his brains after a way out of the difficulty, when Dick's curiosity about geese furnished the very idea he wanted. Bill had robbed the hens' nests before this, as well as the orchard. What was to prevent him from getting a goose's egg?

To be sure, geese were not very nice to have to do with.

Jenny Greenlow, carrying her father's dinner along the riverbank to the Infirmary, where he was at work upon the roof, had been attacked by one and knocked down; and there the child had lain until her father, badly in want of his meal and perplexed at her delay, went along to meet her, and found her half dead with fright, whilst the goose was still feeding on the contents of the basket. But the goose was probably attracted by the smell of the basket's contents; and then Jenny was only a girl! What goose of any sense would dream of molesting a boy! Bill went to work at once to plan the details of the adventure, delighted with the scheme.

Due consideration suggested morning, while the farm men were at breakfast, as the most suitable time for carrying it into effect. So far as he knew, none of them were in the habit of taking their provisions with them. As they all lived in the row adjoining his father's cottage, a mere stone's throw away, they found it pay better to slip in and drink their coffee hot by their own fireside. A few minutes after the stroke of eight, therefore, Bill might make pretty sure that the coast would be clear.

The geese, too, having laid their eggs and been fed, would have wandered away to their pastures. There was only one other thing to be considered. The hole in the hedge through which he meant to creep was behind the shed, but so soon as he crept round to the door, Blazer was sure to catch sight of him; and if Elspeth were anywhere near at hand, his noise was sure to bring her out. Out of this difficulty, however, Bill saw positively no way. The only thing was to hope that Elspeth would be busy waiting on her master just then, and to dare the rest.

"I've done worse things before now," said Bill to himself, by way of encouragement.

Accordingly, next morning he was up with the sun, determined to get quickly through his woodchopping, and the various other duties that were expected of him. On ordinary occasions, Bill was given to being rather slow.

"If you're through too quick, you get more to do next day," was his way of arguing; so he always took care to make his work last out, as a country boy knows how.

But on this morning, he was particularly brisk. He had just finished, and was counting on getting clean off, when he heard his mother's voice.

"Bill!—Oh!—Just done, are you? You've been spry. Here!" As Bill was lounging off. "I just want you to come and help me through with this mangling; and there 'll be time to run with Mrs. Wayling's before daddy comes in to breakfast."

At the first mention of mangling, all Bill's sense of justice had risen in rebellion; but an errand before breakfast fell in with his plans beautifully.

His mother thought he had never come with such alacrity, and wondered what magic it was that regulated the moods and caprices of boyhood. "He's that slow and obstinate by times," she said to herself, as she spread the folded linen ready; "and look at him this morning. Couldn't be a better help if he was a girl, and grown-up!" She little thought.

"Mother," said the wily Bill presently, on coming to the end of a batch. "Mother, I'm awful hungry; and it's a good step to Mrs. Wayling's. Couldn't I have a bit o' summat afore I start out? They keep you such a while up there; likely it'll be half over before I get in."

"To be sure you can," answered his mother, thoroughly pleased with his cheerful industry. And forthwith going to the dresser, she cut and spread a thick slice. "Have what you want afore you go," said she, reckoning to get things cleared up and out of her way, ready for her ironing by and by.

And Bill stood munching hungrily, as he waited to start, turning afresh, and congratulating himself that now, come what might, his breakfast was secure.

It was about half-past seven when he set out for Mrs. Wayling's with the bundle on his head. It was a good distance. Mrs. Wayling was the schoolmaster's wife, and lived up by the church. Bill usually took a barrow; but this time he had his own reasons for wishing to be entirely unencumbered so soon as ever he should have delivered his burden. A barrow would not be handy at stiles, and he intended coming back by the river and the fields, so as to avoid the chance of meeting his father.

Bill was warm by the time he arrived at the schoolhouse. He had got over the ground pretty quickly, considering the weight of his burden, and the church clock still wanted two minutes of the quarter. If only they did not keep him waiting, he would be back at the farm at the very right moment.

As luck would have it, the servant returned almost immediately, to say that her mistress had no change, and would send the money round with the next bundle of linen. And Bill, only too glad to be free, money or no money, nodded and ran off towards the river as fast as his legs would carry him.

It was a good deal farther that way, but Bill had now nothing but himself to carry. In a very short time, he had reached the riverbank, and was hurrying along the towing-path. The geese were already in the field. He saw them marching towards the river in their pompous way, with the old white gander at their head. There would be nothing to fear from them; and, puffing and panting with hurry and excitement, Bill scudded along until he reached the back of the orchard, when he slackened pace and went tiptoe, stealing along behind the hedge towards the hole through which he intended to creep.

It was not much of a gap, for it had grown-up a bit since last Bill had squeezed through—which was when the apples were ripe. But gap or no gap wasn't going to stand in his way just then. Bill got down into the ditch, to wait until he should hear eight strike and the men tramp past to breakfast. He had not long been there when the clock sounded out the hour.

Bill took his hands out of his pockets, and laid hold of a stoutish stem of whitethorn on either side, breaking or bending back the smaller twigs, so as to clear his passage. Then he waited again. He could plainly hear somebody moving about inside the hedge, and he began to be terribly afraid that one of the men had made up his mind to spare himself the trouble of going home to breakfast.

Bill let go the whitethorn stems in dismay.

"There's a go!" exclaimed he to himself. It seemed such a pity, too, when everything was so splendidly arranged. But just then, he heard the footsteps moving towards the door of the shed.

"Gone eight, mate?" asked a voice.

Blazer sprang to his feet and uttered a bark; but there was no other answer.

"Blest if oi yeerd it strike!" exclaimed the voice. "But they be all gone, sarting sure, and oi be left behoind. Oi reckon that 'ere clock bean't much account. 'Twants a bigger clapper to t' bell."

And with these words, the door banged to, and the hobnails went dragging across the yard. It was old Jaggers, the cowman, who was as deaf as a post, and was always getting "left behind" if his mates forgot to hail him when the breakfast hour arrived.

The coast was clear at last. Bill laid hands anew on the whitethorn stems. But at that very moment, a dull thud, thud, in his other ear made him stop short. It was a sound of approaching footsteps on the worn grass of the footway. Some one was coming along from the river-side. Would interruptions never cease? Bill gave a guilty look round. It would not do to be seen in the ditch.

A yard or two to the right was a large bramble bush, which had sprung up on the field and straggled over to the hedge, catching hold of the whitethorn with its thorny arms, and interlacing with the blackberry brambles in a thick tangle. Under this shelter, he crept to hide.

Thud, thud came the steps, nearer and nearer. A few minutes more and he would be able to come out. But just as the passer-by reached the very spot where Bill crouched in hiding, the footsteps suddenly ceased.

Bill was puzzled. Who could it be? And why had he stopped exactly there? Bill was shrewd enough to know that if he could not see, neither could he be seen; but it was too bad to be obliged to stop there whilst the moments of that precious half-hour were running to waste.

At length, impatience got the better of prudence, and he determined to get a peep, at the risk of being discovered. With this intent, he commenced creeping by inches towards the limit of his shelter. But a boy's eyes cannot be in two places at once. In his anxiety to keep a watch on the bank, he entirely forgot the necessity of looking to his feet. At the very moment when he caught sight of a well-blacked boot, down slipped his foot into a deep hole, and poor, luckless Bill suddenly found himself measuring his length at the bottom of the ditch.

"Hullo!" exclaimed a voice from above. "What's up?"

Bill was not hurt; but he lay quiet, still hoping to escape discovery. The owner of the voice, however, to whom the boot also belonged, was not likely to be so easily satisfied.

"What's up?" repeated he, facing about, and seeing to his infinite astonishment a somewhat unkempt figure sprawling at the bottom of the ditch.

Finding concealment impossible, Bill scrambled to his feet with a sheepish grin.

"What are you after?" asked the stranger.

He was dressed in a suit of dark-coloured tweed, and had under his arm what looked like a bundle of deal sticks and a flat, square package buckled up in a shiny black case. Bill's rapid survey satisfied him that he did not belong to the neighbourhood, and that it was therefore safe to tell as many lies as ingenuity could invent.

"Rats," answered he promptly. "Got a hole here; and they steals the eggs."

"Ah!" observed the gentleman. "And you get so much a head for them, eh?"

Bill nodded.

The gentleman turned on his heel, laughing to himself at the idea that any rat should be so unwary as to come out of his hole when somebody was by to knock him on the head. A minute later, he had forgotten the whole thing, and relapsed into his former attitude, looking away across the fields to the right. He was an artist, and had come down by rail to make the best of the mild spring day; for there was an open view of the church from that point before the leaves were thick.

Bill, not knowing all this, stood at the bottom of the ditch staring at his back, and wondering what spirit of contrariness could possess him that he must choose that very spot to loiter on. He was just thinking whether it would be safe to leave him out of the question altogether, and proceed to the business of getting through the hedge, when the gentleman faced about again.

"Hullo!" said he, unrolling the bundle of sticks under his arm as he spoke, and nodding towards the farm. "You don't work there?"

Bill shook his head. "My father does though," answered he.

"You couldn't borrow a chair for me, I suppose," said the gentleman. "They know you, I daresay."

Bill stared for a minute or two, then suddenly broke into a grin. "Dessay I could," said he.

"Well, look sharp!" returned the gentleman. "And I'll give you a copper."

To his infinite astonishment, Bill had no sooner received the order, than he advanced a few steps along the ditch, turned his face to the hedge, and seizing firm hold of the two whitethorn sterns, commenced drawing himself through the gap.

"He knows how to take an order," said the artist to himself. "That's what I call going the shortest cut."

Meanwhile, Bill's mental comment was, "My! If he ha'n't nearly done me!" And he made like a shot for the door of the shed, casting a rapid glance towards Blazer's kennel, to see if he were on the watch. For once, however, Blazer was otherwise occupied, and Bill gained the shed unobserved.

"CONSCIENCE MAKES COWARDS OF US ALL."

ON first peeping into the shed, Bill was disconcerted to see a goose on one of the nests.

But Bill was no coward when there was anything to be gained. He went cautiously forward towards the furthest boxes, keeping an eye on the sitting bird the while, and ready to beat a retreat on the first alarm. But the goose had no intention of quitting her position. She only raised her head with a little warning scream and hiss; and he reached the nests without further challenge.

Bill uttered an exclamation of delight. In the first nest were three eggs; in the second, two. "Let's make 'em even," said he, possessing himself of the odd egg, and stowing it carefully in his jacket-tail.

Just as he was about to turn, however, an idea came to him. Ten to one such a splendid chance would not return in a hurry. "One a-piece 'll be fairer," said he, taking an egg from the other nest, and tucking it in the opposite pocket. "They can lay another," added he, with a grin. Then he recrossed the shed, and regained the door.

Peeping round, before venturing out, he saw that Blazer had come out of his kennel, and was standing on the alert, waiting for somebody to bark at. Bill's first impulse was to draw back. Perhaps the dog had heard the goose's scream. But second thought convinced him that to think of remaining longer in the shed was useless, and that, in fact, the sooner he got out of it the better, since by this time it must be very close on half-past eight. With another glance at Blazer, he slipped out and darted round the side of the shed. But Blazer had seen him, and dashed forward on his chain with a furious bark.

Bill turned, terrified, half expecting to see Blazer on his heels; and not looking to see where he was going, ran full tilt against the corner of the shed, leaving the print of a louvre-board on his eyebrow. But anyhow he was safe behind the shed, and Blazer was not loose.