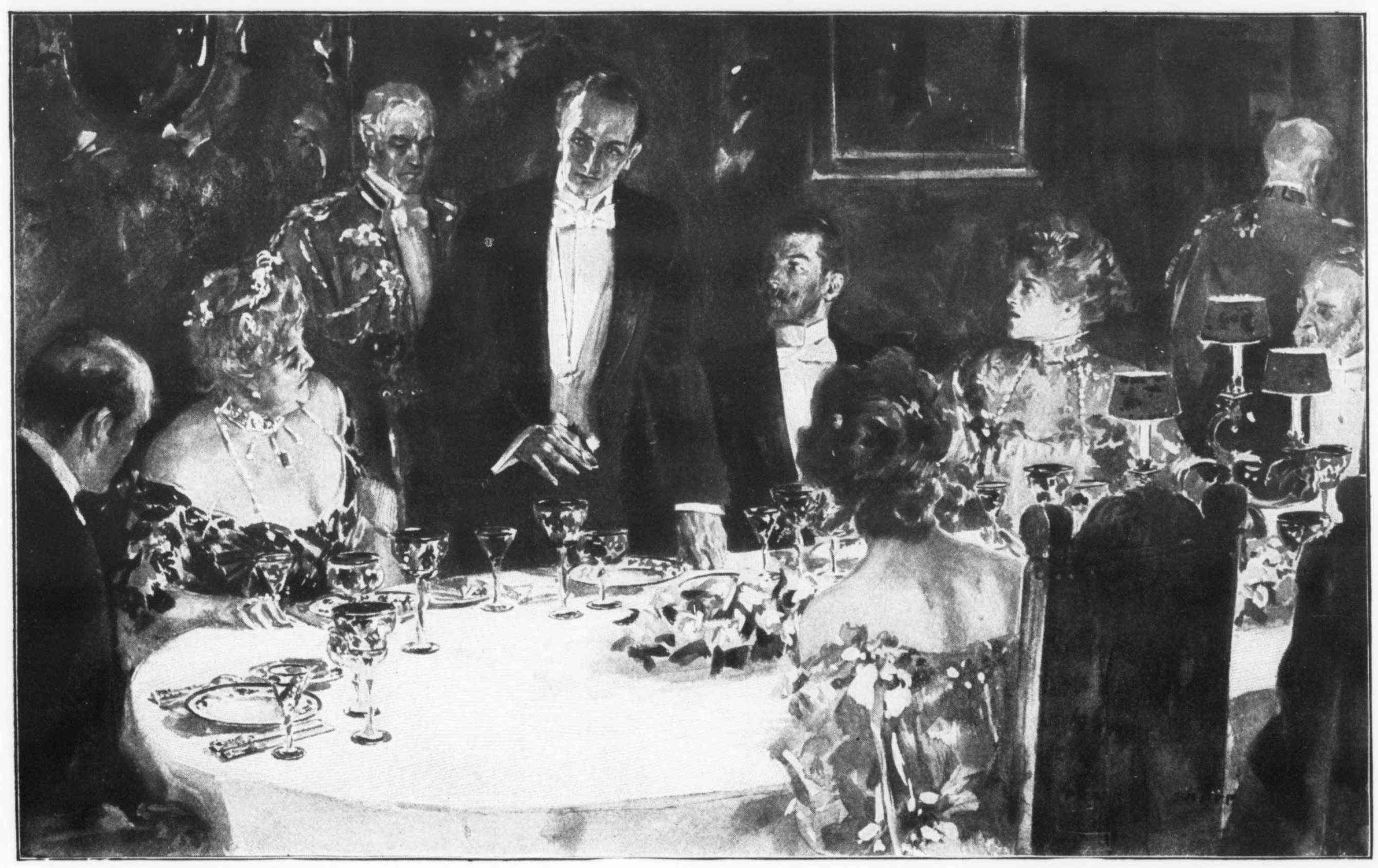

It was a rather dim daylight dinner. I remember that quite distinctly, for I could see the glow of the sunset over the trees in the park, through the high window at the west end of the dining-room. I had expected to find a larger party, I believe, for I recollect being a little surprised at seeing only a dozen people assembled at table. It seemed to me that in old times, ever so long ago, when I had last stayed in that house, there had been as many as thirty or forty guests. I recognized some of them among a number of beautiful portraits that hung on the walls. There was room for a great many because there was only one huge window, at one end, and one large door at the other. I was very much surprised, too, to see a portrait of myself, evidently painted about twenty years ago by Lenbach. It seemed very strange that I should have so completely forgotten the picture, and that I should not be able to remember having sat for it. We were good friends, it is true, and he might have painted it from memory, without my knowledge, but it was certainly strange that he should never have told me about it. The portraits that hung in the dining-room were all very good indeed and all, I should say, by the best painters of that time.

My left-hand neighbor was a lovely young girl whose name I had forgotten, though I had known her long, and I fancied that she looked a little disappointed when she saw that I was beside her. On my right there was a vacant seat, and beyond it sat an elderly woman with features as hard as the overwhelmingly splendid diamonds she wore. Her eyes made me think of gray glass marbles cemented into a stone mask. It was odd that her name should have escaped me, too, for I had often met her.

The table looked irregular, and I counted the guests mechanically while I ate my soup. We were only twelve, but the empty chair beside me was the thirteenth place.

I suppose it was not very tactful of me to mention this, but I wanted to say something to the beautiful girl on my left, and no other subject for a general remark suggested itself. Just as I was going to speak I remembered who she was.

“Miss Lorna,” I said, to attract her attention, for she was looking away from me toward the door, “I hope you are not superstitious about there being thirteen at table, are you?”

“We are only twelve,” she said, in the sweetest voice in the world.

“Yes; but some one else is coming. There’s an empty chair here beside me.”

“Oh, he doesn’t count,” said Miss Lorna quietly. “At least, not for everybody. When did you get here? Just in time for dinner, I suppose.”

“Yes,” I answered. “I’m in luck to be beside you. It seems an age since we were last here together.”

“It does indeed!” Miss Lorna sighed and looked at the pictures on the opposite wall. “I’ve lived a lifetime since I saw you last.”

I smiled at the exaggeration. “When you are thirty, you won’t talk of having your life behind you,” I said.

“I shall never be thirty,” Miss Lorna answered, with such an odd little air of conviction that I did not think of anything to say. “Besides, life isn’t made up of years or months or hours, or of anything that has to do with time,” she continued. “You ought to know that. Our bodies are something better than mere clocks, wound up to show just how old we are at every moment, by our hair turning gray and our teeth falling out and our faces getting wrinkled and yellow, or puffy and red! Look at your own portrait over there. I don’t mind saying that you must have been twenty years younger when that was painted, but I’m sure you are just the same man to-day—improved by age, perhaps.”

I heard a sweet little echoing laugh that seemed very far away; and indeed I could not have sworn that it rippled from Miss Lorna’s beautiful lips, for though they were parted and smiling my impression is that they did not move, even as little as most women’s lips are moved by laughter.

“Thank you for thinking me improved,” I said. “I find you a little changed, too. I was just going to say that you seem sadder, but you laughed just then.”

“Did I? I suppose that’s the right thing to do when the play is over, isn’t it?”

“If it has been an amusing play,” I answered, humoring her.

The wonderful violet eyes turned to me, full of light. “It’s not been a bad play. I don’t complain.”

“Why do you speak of it as over?”

“I’ll tell you, because I’m sure you will keep my secret. You will, won’t you? We were always such good friends, you and I, even two years ago when I was young and silly. Will you promise not to tell anyone till I’m gone?”

“Gone?”

“Yes. Will you promise?”

“Of course I will. But——” I did not finish the sentence, because Miss Lorna bent nearer to me, so as to speak in a much lower tone. While I listened, I felt her sweet young breath on my cheek.

“I’m going away to-night with the man who is to sit at your other side,” she said. “He’s a little late—he often is, for he is tremendously busy; but he’ll come presently, and after dinner we shall just stroll out into the garden and never come back. That’s my secret. You won’t betray me, will you?”

Again, as she looked at me, I heard that far-off silver laugh, sweet and low. I was almost too much surprised by what she had told me to notice how still her parted lips were, but that comes back to me now, with many other details.

“My dear Miss Lorna,” I said, “do think of your parents before taking such a step!”

“I have thought of them,” she answered. “Of course they would never consent, and I am very sorry to leave them, but it can’t be helped.”

At this moment, as often happens when two people are talking in low tones at a large dinner-table, there was a momentary lull in the general conversation, and I was spared the trouble of making any further answer to what Miss Lorna had told me so unexpectedly, and with such profound confidence in my discretion.

To tell the truth, she would very probably not have listened, whether my words expressed sympathy or protest, for she had turned suddenly pale, and her eyes were wide and dark. The lull in the talk at table was due to the appearance of the man who was to occupy the vacant place beside me.

He had entered the room very quietly, and he made no elaborate apology for being late, as he sat down, bending his head courteously to our hostess and her husband, and smiling in a gentle sort of way as he nodded to the others.

“Please forgive me,” he said quietly. “I was detained by a funeral and missed the train.”

It was not until he had taken his place that he looked across me at Miss Lorna and exchanged a glance of recognition with her. I noticed that the lady with the hard face and the splendid diamonds, who was at his other side, drew away from him a little, as if not wishing even to let his sleeve brush against her bare arm. It occurred to me at the same time that Miss Lorna must be wishing me anywhere else than between her and the man with whom she was just about to run away, and I wished for their sake and mine that I could change places with him.

He was certainly not like other men, and though few people would have called him handsome there was something about him that instantly fixed the attention; rarely beautiful though Miss Lorna was, almost everyone would have noticed him first on entering the room, and most people, I think, would have been more interested by his face than by hers. I could well imagine that some women might love him, even to distraction, though it was just as easy to understand that others might be strongly repelled by him, and might even fear him.

For my part, I shall not try to describe him as one describes an ordinary man, with a dozen or so adjectives that leave nothing to the imagination but yet offer it no picture that it can grasp. My instinct was to fear him rather than think of him as a possible friend, but I could not help feeling instant admiration for him, as one does at first sight for anything that is very complete, harmonious, and strong. He was dark, and pale with a shadowy pallor I never saw in any other face; the features of thrice-great Hermes were not modeled in more perfect symmetry; his luminous eyes were not unkind, but there was something fateful in them, and they were set very deep under the grand white brow. His age I could not guess, but I should have called him young; standing, I had seen that he was tall and sinewy, and now that he was seated, he had the unmistakable look of a man accustomed to be in authority, to be heard and to be obeyed. His hands were white, his fingers straight, lean, and very strong.

Everyone at the table seemed to know him, but as often happens among civilized people, no one called him by name in speaking to him.

“We were beginning to be afraid that you might not get here,” said our host.

“Really?” The Thirteenth Guest smiled quietly, but shook his head. “Did you ever know me to break an engagement, under any circumstances?”

The master of the house laughed, though not very cordially, I thought. “No,” he answered. “Your reputation for keeping your appointments is proverbial. Even your enemies must admit that.”

The Guest nodded and smiled again. Miss Lorna bent toward me.

“What do you think of him?” she asked, almost in a whisper.

“Very striking sort of man,” I answered, in a low tone. “But I’m inclined to be a little afraid of him.”

“So was I, at first,” she said, and I heard the silver laugh again. “But that soon wears off,” she went on. “You’ll know him better some day!”

“Shall I?”

“Yes; I’m quite sure you will. Oh, I don’t pretend that I fell in love with him at first sight! I went through a phase of feeling afraid of him, as almost everyone does. You see, when people first meet him they cannot possibly know how kind and gentle he can be, though he is so tremendously strong. I’ve heard him called cruel and ruthless and cold, but it’s not true. Indeed it’s not! He can be as gentle as a woman, and he’s the truest friend in all the world.”

I was going to ask her to tell me his name, but just then I saw that she was looking at him, across me, and I sat as far back in my chair as I could, so that they might speak to each other if they wished to. Their eyes met, and there was a longing light in both—I could not help glancing from one to the other—and Miss Lorna’s sweet lips moved almost imperceptibly, though no sound came from them. I have seen young lovers make that small sign to each other even across a room, the signal of a kiss given and returned in the heart’s thoughts.

If she had been less beautiful and young, if the man she loved had not been so magnificently manly, it would have irritated me; but it seemed natural that they should love and not be ashamed of it, and I only hoped that no one else at the table had noticed the tenderly quivering little contraction of the young girl’s exquisite mouth.

“You remembered,” said the man quietly. “I got your message this morning. Thank you.”

“I hope it’s not going to be very hard,” murmured Miss Lorna, smiling. “Not that it would make any great difference if it were,” she added more thoughtfully.

“It’s the easiest thing in life,” he said, “and I promise that you shall never regret it.”

“I trust you,” the young girl answered simply.

Then she turned away, for she no doubt felt the awkwardness of talking to him across me of a secret which she had confided to me without letting him know that she had done so. Instinctively I turned to him, feeling that the moment had come for disregarding formality and making his acquaintance, since we were neighbors at table in a friend’s house and I had known Miss Lorna so long. Besides, it is always interesting to talk with a man who is just going to do something very dangerous or dramatic and who does not guess that you know what he is about.

“I suppose you motored here from town, as you said you missed the train,” I said. “It’s a good road, isn’t it?”

“Yes, I literally flew,” replied the dark man, with his gentle smile. “I hope you’re not superstitious about thirteen at table?”

“Not in the least,” I answered. “In the first place, I’m a fatalist about everything that doesn’t depend on my own free will. As I have not the slightest intention of doing anything to shorten my life, it will certainly not come to an abrupt end by any autosuggestion arising from a silly superstition like that about thirteen.”

“Autosuggestion? That’s rather a new light on the old belief.”

“And secondly,” I continued, “I don’t believe in death. There is no such thing.”

“Really?” My neighbor seemed greatly surprised. “How do you mean?” he asked. “I don’t think I understand you.”

“I’m sure I don’t,” put in Miss Lorna, and the silver laugh followed. She had overheard the conversation, and some of the others were listening, too.

“You don’t kill a book by translating it,” I said, rather glad to expound my views. “Death is only a translation of life into another language. That’s what I mean.”

“That’s a most interesting point of view,” observed the Thirteenth Guest thoughtfully. “I never thought of the matter in that way before, though I’ve often seen the expression ‘translated’ in epitaphs. Are you sure that you are not indulging in a little paronomasia?”

“What’s that?” inquired the hard-faced lady, with all the contempt which a scholarly word deserves in polite society.

“It means punning,” I answered. “No, I am not making a pun. Grave subjects do not lend themselves to low forms of humor. I assure you, I am quite in earnest. Death, in the ordinary sense, is not a real phenomenon at all, so long as there is any life in the universe. It’s a name we apply to a change we only partly understand.”

“Learned discussions are an awful bore,” said the hard-faced lady very audibly.

“I don’t advise you to argue the question too sharply with your neighbor there,” laughed the master of the house, leaning forward and speaking to me. “He’ll get the better of you! He’s an expert at what you call ‘translating people into another language.’”

If the man beside me was a famous surgeon, as our host perhaps meant, it seemed to me that the remark was not in very good taste. He looked more like a soldier.

“Does our friend mean that you are in the army, and that you are a dangerous person?” I asked of him.

“No,” he answered quietly. “I’m only a King’s Messenger, and in my own opinion I’m not at all dangerous.”

“It must be rather an active life,” I said, in order to say something; “constantly coming and going, I suppose?”

“Yes, constantly.”

I felt that Miss Lorna was watching and listening, and I turned to her, only to find that she was again looking beyond me, at my neighbor, though he did not see her. I remember her face very distinctly as it was just then; the recollection is, in fact, the last impression I retain of her matchless beauty, for I never saw her after that evening.

It is something to have seen one of the most beautiful women in the world gazing at the man who was more to her than life and all it held; it is something I cannot forget. But he did not return her look just then, for he had joined in the general conversation, and very soon afterward he practically absorbed it.

He talked well; more than well, marvelously; for before long even the lady with the hard face was listening spellbound, with the rest of us, to his stories of nations and tales of men, brilliant descriptions, anecdotes of heroism and tenderness that were each a perfect coin from the mint of humanity, with dashes of daring wit, glimpses of a profound insight into the great mystery of the beyond, and now and then a manly comment on life that came straight from the heart: never, in all my long experience, have I heard poet, or scholar, or soldier, or ruler of men talk as he did that evening. And as I listened I was more and more amazed that such a man should be but a simple King’s Messenger, as he said he was, earning a poor gentleman’s living by carrying his majesty’s despatches from London to the ends of the earth, and I made some sad and sober inward reflections on the vast difference between the gift of talking supremely well and the genius a man must have to accomplish even one little thing that may endure in history, in literature, or in art.

“Do you wonder that I love him?” whispered Miss Lorna.

Even in the whisper I heard the glorious pride of the woman who loves altogether and wholly believes that there is no one like her chosen man.

“No,” I answered, “for it is no wonder. I only hope——” I stopped, feeling that it would be foolish and unkind to express the doubt I felt.

“You hope that I may not be disappointed,” said Miss Lorna, still almost in a whisper. “That was what you were going to say, I’m sure.”

I nodded, in spite of myself, and met her eyes; they were full of a wonderful light.

“No one was ever disappointed in him,” she murmured—“no living being, neither man, nor woman, nor child. With him I shall have peace and love without end.”

“Without end?”

“Yes. Forever and ever!”

After dinner we scattered through the great rooms in the soft evening light of mid-June, and by and by I was standing at an open window, with the mistress of the house, looking out across the garden.

In the distance, Lorna was walking slowly away down the broad avenue with a tall man; and while they were still in sight, though far away, I am sure that I saw his arm steal round her as if he were drawing her on, and her head bent lovingly to his shoulder; and so they glided away into the twilight and disappeared.

Then at last I turned to my hostess. “Do you mind telling me the name of that man who came in late and talked so well?” I asked. “You all seemed to know him like an old friend.”

She looked at me in profound surprise. “Do you mean to say that you do not know who he is?” she asked.

“No. I never met him before. He is a most extraordinary man to be only a King’s Messenger.”

“He is indeed the King’s Messenger, my dear friend. His name is Death.”

I dreamed this dream one afternoon last summer, dozing in my chair on deck, under the double awning, when the Alda was anchored off Goletta, in sight of Carthage, and the cool north breeze was blowing down the deep gulf of Tunis. I must have been wakened by some slight sound from a boat alongside, for when I opened my eyes my man was standing a little way off, evidently waiting till I should finish my nap. He brought me a telegram which had just come on board, and I opened it rather drowsily, not expecting any particular news.

It was from England, from a very dear friend.

Lorna died suddenly last night at Church Hadley.

That was all; the dream had been a message.

“With him I shall have peace and love without end.”

Thank God, I hear those words in her own voice, whenever I think of her.

Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in the November 1907 issue of Cosmopolitan Magazine.