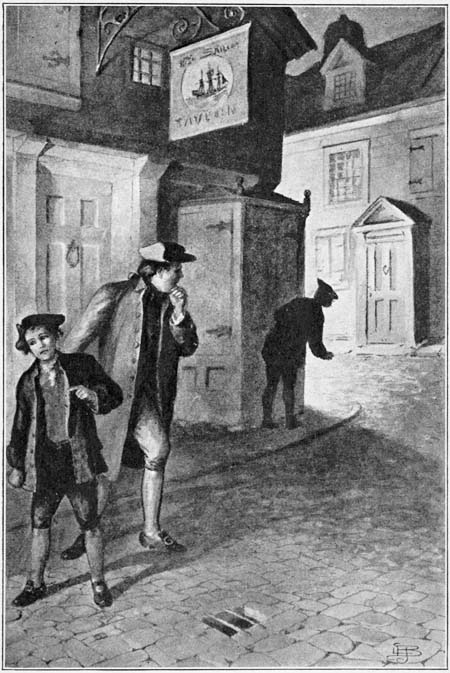

“WHICH WAY DID HE GO?”

THE MINUTE BOYS OF

PHILADELPHIA

BY

JAMES OTIS

Author of “The Minute Boys of Long Island,” “The Minute

Boys of Wyoming Valley,” “Boys of ’98,” “Teddy and

Carrots,” “Boys of Fort Schuyler,” “Under the

Liberty Tree,” etc., etc.

Illustrated by

L. J. BRIDGMAN

BOSTON

DANA ESTES AND COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1911

By Dana Estes & Company

All rights reserved

THE MINUTE BOYS OF PHILADELPHIA

Electrotyped and Printed by

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. Simonds & Co., Boston, U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Spy | 11 |

| II. | The Suggestion | 33 |

| III. | Skinny Baker | 57 |

| IV. | The Recruits | 76 |

| V. | At Swede’s Ford | 96 |

| VI. | Valley Forge | 117 |

| VII. | In Mortal Fear | 136 |

| VIII. | The Carnival | 156 |

| IX. | On Duty | 173 |

| X. | In the Lion’s Mouth | 194 |

| XI. | At Barren Hill | 213 |

| XII. | The Retreat | 231 |

| XIII. | Turning the Tables | 249 |

| XIV. | A Warm Place | 268 |

| XV. | A Narrow Escape | 287 |

| XVI. | The Attack | 305 |

| PAGE | |

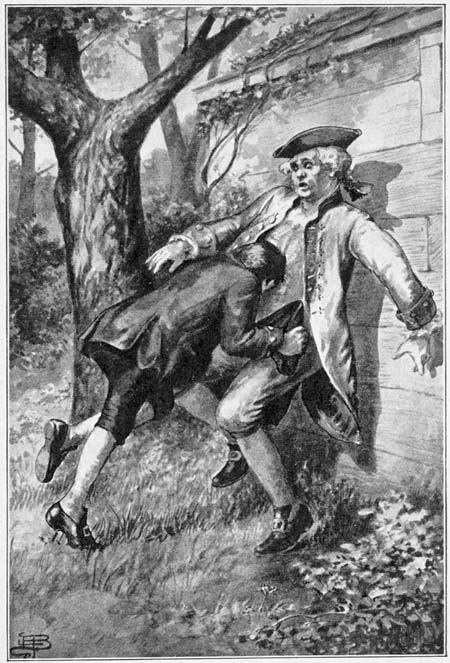

| “Which way did he go?” (Page 18) | Frontispiece |

| We kept strict watch ahead and behind | 40 |

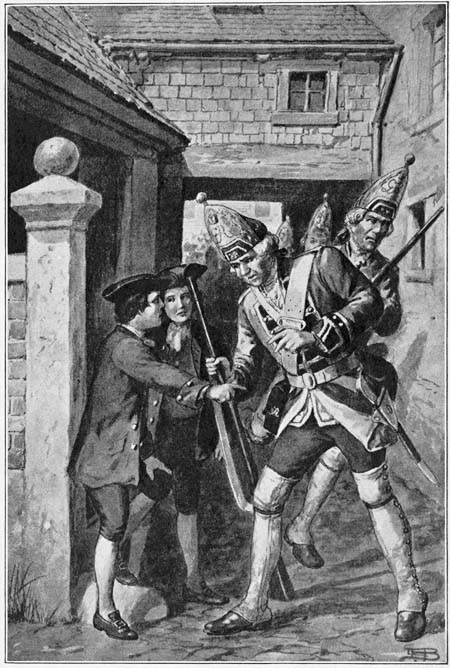

| “I could kill you and not call it murder” | 72 |

| “This, General Varnum, is Richard Salter” | 113 |

| He found two lobster-backs guarding the entrance | 144 |

| Scaling the jail wall | 191 |

| In a twinkling Jeremy was upon him | 258 |

| Butting him full in the pit of the stomach | 296 |

THE MINUTE BOYS OF

PHILADELPHIA

In striving to set down what we boys of Philadelphia did during a portion of the time when General Howe and his lobster-backs held possession of our city, I have no intention of blowing my own horn.

If, however, it should appear from what I write that I have made myself seemingly of more consequence than is my due, it must be set down as excuse that I am earnestly endeavoring to give a true, faithful account of our work, for some of us lads of Philadelphia did, so we have been told by those who stand high in the American army, very much good for the patriot cause in our own small way.

It is needless for me to go into details regarding General Howe’s occupation of the city, for the facts are well known. I question if there be a boy in all these colonies who does not remember how we of Philadelphia suffered when the lobster-backs held possession of the city.

It is written in history by this time, that we who[12] held to the Cause were sadly put upon by those whom the king sent overseas to whip us into subjection. It may be there are some outside this city of Philadelphia who think we might have done more in our own defence; but I dare venture to say you will agree with me, if it so please you to believe all I have written, when I say that we, meaning men, women and children, did whatsoever we could for the Cause at such times as it was possible to do so without endangering our lives.

In more cases than one have I seen even the women render aid which would have cost them the halter, if so be General Howe, or General Clinton who came later, had had an idea of what was going on.

Do you remember the battle of Germantown, as some people call it, that fight which took place near the Chew house? Well, it was about six months afterward, when the spring had fully come, that Jeremy Hapgood, my particular friend, and I, who am by name known as Richard Salter, had agreed among ourselves that we would attend a vendue of horses to be held at the London Coffee-House, which is situate on the corner of High and Front streets, as of course you know.

To our minds, the only important matter concerning this vendue was that there were several fine animals to be sold, and among them mayhap four or five which the British officers had seized from our people nearabout Germantown, claiming a right to take them in the name of the king because their owners were said to favor the Cause.

We lads were not the only persons in Philadelphia with a leaning towards independence, who counted to be at the vendue that day, for I had[13] heard it whispered about by Master Norris, who, as you know, is a most peaceable man, being a Friend, that there was a chance some attempt might be made during the sale to carry off the horses which had been much the same as stolen.

Jeremy and I were minded to know what would be done, hoping there might be some chance for us to lend a hand, and realizing that it would be a credit to us if we could say we had had some part in cutting the combs, however slightly, of these lobster-backs who paraded the streets shouldering into the gutters all of our people who dared hold the sidewalk when their high mightinesses were inclined to use it.

Now, as you know, the London Coffee-House was a famous resort for those minions of the king, and we lads generally gave that part of the city a wide berth, not being minded to bear insult, nay, even blows, when it so pleased the lobster-backs to inflict them.

To the end that we might see what was going on and at the same time remain at a respectful distance from the red-coated gentry, I proposed to Jeremy that we meet in front of that shop at the corner of Front street and Black Horse alley which was formerly Mrs. Roberts’ coffee-house, and there we would not only be at a safe distance from the Britishers who were likely to be in a disagreeable mood from overly much drinking; but, in addition could, if need arose, readily make our escape.

You must know that at the rear of the store was a gate opening on Chestnut street, where, when the place had been used as a coffee-house, the gentlemen’s horses were brought in to the stable, and through that gate we might readily give any lobster-back[14] the slip unless, peradventure, he was fleeter of foot than we; but there were few in Philadelphia at that time who could outstrip either Jeremy or me in a race.

Well, as we had agreed so we did, and on coming in front of the shop we could see on the corner of High street a large throng gathered, nearly every one of whom, save, of course, the grooms, wore a red coat, and I said to Jeremy that it was in my mind Master Norris had repented of taking any part in the rescue of the horses, after learning that so many of the soldiers were gathered.

As a matter of fact, it would have been a mighty disagreeable task to run off any of the animals while such a crowd of officers was nearby, with here and there a squad of soldiers who had gathered by themselves, not daring to approach too near to their high and mighty masters.

“If Isaac Norris and his friends had any design to run off the beasts, then the work should have been done last night while they were stabled, rather than wait until now, for even the thickest head in Philadelphia could understand that with so many fine horses offered for sale, the king’s army would be well represented at this vendue,” Jeremy Hapgood said grimly, half turning as if it was in his mind to beat a retreat, for it would profit us little to remain so far from the vendue, if peradventure we were eager to hear and to see all that was going on.

The animals had not yet been brought out for sale, and it appeared to me that the waiting ones were impatient, so much so, in fact, that there was seemingly considerable excitement nearby the entrance to the coffee-house, although what had caused[15] it I could not even so much as guess, and it was on my tongue’s end to propose to Jeremy that we go down to the water front nearby the Jolly Tar inn, where we had for some time kept concealed a skiff.

Now it may sound much as if I am straining the truth when I say that we two lads had kept hidden from the Britishers all this while a boat, for, as you well know, it was near akin to a crime for one of us so-called rebels of Philadelphia to have a craft of any kind in his possession.

Every boat and vessel on the river had either been destroyed or taken in charge by the lobster-backs, as if they were fearful that some of us enemies to the king might try to get away from their not overly pleasant company by taking to the water, and that their hold of Philadelphia would be weakened if man, woman or child was permitted to leave the city.

As I have said, it was on the tip of my tongue to tell Jeremy that we were but wasting our time here while we could be more pleasantly employed elsewhere, when there arose a sudden commotion nearby the door of the coffee-house, and in a twinkling I saw three of the red-coated, swaggering officers fall to the ground as if suddenly stricken with death.

Almost at the same instant from out amid the throng there appeared a man dressed in the garb of a countryman, who, from outward appearance, might have been one of the farmers nearby, and who, thinking more of the dollars than of his country’s freedom, was ready to serve the Britishers with meat and vegetables, if so be he received therefor sufficient of hard money.

This fellow came out with a bound, and he it[16] was who had overturned the lobster-backs. Almost before I could fairly understand what had happened, he was coming in the direction of Jeremy and me at full speed, while behind him rose such cries as:

“Kill him! A spy, a spy! Take after him, you idlers; don’t you see that he is a spy and escaping?”

Jeremy and I needed no further introduction to this fleeing stranger. The fact that the Britishers were bent on capturing him, and accused him of being a spy, which was much the same as declaring he was one who had devoted himself to the Cause, was enough to make him our friend, and in a twinkling, fortunately, I had my wits about me sufficiently to realize that we could open up to him a way of escape, if so be the lobster-backs did not press too closely on his heels.

I knew full well that if I was seen to give aid to one suspected of being a spy, my shrift would be short indeed, for General Howe’s officers made quick work of us people of Philadelphia who were suspected of having lost our love for the king. Therefore it was that I ran forward as if to seize the man, and did lay hold of him with one hand, striving as if it was my purpose to detain him, while at the same time I said loudly, realizing that the uproar behind us was so great that the words would not be overheard:

“Get into the alley-way this side the shop! There is a gate leading to Chestnut street, if so be you are minded to go through; but you should be able to find a hiding place in the old stables, while Jeremy and I keep on as if in pursuit, making them think you have passed that way.”

Then it was I threw myself to the ground, as if[17] he who was shouted after as a spy had thrown me off roughly; but was able to scramble to my feet before the foremost of the pursuers came up.

It was well I moved quickly, otherwise Jeremy might have brought us all to grief, for he failed utterly of understanding why it was I would do anything to aid in the capture of the man. He looked at me in open-mouthed astonishment with reproach written on every feature of his face, until, seizing him by the coat-sleeve, I dragged him on with me as I shouted at the full strength of my lungs:

“A spy, a spy! Come all you good people and catch the spy!”

“What is the meaning of this?” Jeremy asked angrily. “How does it chance that you are joining with the lobster-backs in chasing down one of our people?”

“Have your wits about you, Jeremy Hapgood, else are you like to get me into serious trouble!” I whispered angrily. “Follow my example, and it may be that peradventure we can help this unhappy man who is risking his life for the Cause.”

Then, literally dragging Jeremy along with me, I continued on as if in pursuit of the spy, darting close at his heels up the narrow passage leading to the ruined stables, and from there to the gate which let on Chestnut street.

To my satisfaction, I saw him make a plunge among the decaying timbers much as does one who, swimming, dives into deeper water, and without slackening pace I threw open the gate leading on to Chestnut street, where I made as if I had hurt my leg; but all the while continuing to cry:

“A spy, a spy! Catch the spy!”

[18]“What has come upon you?” Jeremy asked sharply. “I fail to understand any portion of this game.”

“It makes little difference whether you understand it or not, Jeremy Hapgood,” I replied sharply. “Your part is to follow my example, if peradventure you are so thick-headed as not to be able to look through a ladder. You know as well as I, that the man went out of here, and I would have caught him but for the fact that he kicked me on the knee.”

Then it was that Jeremy began to have an inkling of how I would help the poor fellow who was so sorely pressed, and a smile of satisfaction came over his face which would have been fatal to my plans if the lobster-backs had come up in sufficient time to see it.

It was necessary the foremost of the pursuers should run a full half-square before they could come to where we were standing, and no less than a minute passed from the time I threw open the gate before the leaders came up, shouting wildly:

“Which way did he go? Why have you halted in the chase? Where is he?”

“He passed out through this gate not many seconds ago, disabling me by a kick as he went, else I would have caught the fellow,” was my reply.

Now, as a matter of course, all this was a lie, and strictly speaking, so my mother would say, no lad has a right to tell that which is false. But I have heard Master Norris, who is as straight a Friend as can be found in Philadelphia, and a most truthful man, say that in these troublous times he believes we are warranted in telling the enemies[19] of our country things which are not true, if so be good can come to the Cause thereby.

Surely in this falsehood of mine good must come to the Cause, if peradventure the man whom I knew to be hiding under the timbers of the stable, was indeed a spy who had come down from Valley Forge, mayhap, with the hope of finding such a condition of affairs as would warrant our people in making an attempt to retake Philadelphia.

Now, as a matter of course, we lads knew nothing whatsoever of military matters, and wondered greatly why it was all our people should suffer as they had been suffering at Valley Forge, without making some attempt to relieve us who were shut up by the lobster-backs much the same as prisoners.

It seemed to me that if I were a soldier I would prefer to fight, no matter how great the odds might be against me, than remain idle, half-starved, half-frozen, half-clad, awaiting a favorable opportunity.

However, as I have said, and as you know full well, my knowledge of military matters was slight, and in my foolishness, on hearing that a spy had been discovered in the coffee-house, I believed he could have been sent for no less a purpose than to learn what he might to aid our people in making ready for an attack. And as I stood there by the gate, with the lobster-backs streaming past me, each asking querulously which way the game had gone, I could almost fancy I saw those patriots from Valley Forge coming down through Germantown to square accounts.

It goes without saying that the Britishers did not continue the chase very far up Chestnut street,[20] because of not being able to see the man they were so eager to catch, and after running a dozen yards, mayhap, one by one they turned back to question Jeremy and me as to the direction which the fugitive had taken.

I thought of what Master Norris had said regarding truth-telling when it came to a question of saving a man’s life, and to the best of my ability I explained how I had seen the man run up the street after passing through the gate, and then, as my attention was attracted for an instant to Jeremy, I turned my head to look again; but saw nothing of him.

Therefore it was, so I said, that he must have taken refuge in some one of the houses or outbuildings between where we stood and, mayhap, the distance of a square.

By this time Jeremy had succeeded in getting through his head, which it seemed to me had never been so thick as on this day, somewhat of the plan in my mind, and bravely did he second my efforts to throw the lobster-backs off the track.

He also declared that he had seen the stranger running up the street; had followed him a certain distance, and declared that but for the blow which the fellow gave me, we two lads would have secured him. In other ways Master Hapgood bolstered up his story and mine in such fashion, that unless there had been serious cause for suspicion, the Britishers could have done no less than believe all we told them.

The result was that very speedily we were left alone, for not above twenty had followed the man through the alley-way, and many of these had gone back to the coffee-house to explain how the[21] supposed spy had succeeded in giving them the slip.

Within five minutes we were alone, standing in the gateway where we could see all that might take place on Chestnut street in either direction, as well as make certain whether anyone came upon us from the rear.

Thus we were, as you might say, absolutely alone, and Jeremy said to me in a whisper:

“Now what is your intent, Richard Salter? It strikes me that this is your affair, and I am well content to do whatsoever you shall say.”

I knew not what reply to make, and verily an older head than mine might have been puzzled to decide exactly what was best to be done, for there was need of much caution since a man’s life depended upon the decision that should be made.

I had succeeded in saving the stranger, whoever he might be, for the time being, and now it stood me in hand to do whatsoever I might toward finishing the job in proper fashion. But how the matter was to be worked puzzled me beyond words to describe.

Jeremy waited while one might have counted twenty, for me to reply to his question, and then repeated it in a different form:

“You have got your spy underneath the timbers of the stable, and within a stone’s throw of where the king’s officers most do congregate. Now, how are you to prevent the poor fellow from starving to death?”

“It is a question which I wish most heartily I might be able to answer, Jeremy,” I replied soberly, cudgeling my brains meanwhile for some solution to the difficulty.

[22]However, there was in my mind the fact that I could not make any move at once, because of the danger that the lobster-backs who had gone up Chestnut street might come back into the yard, therefore I said to the lad, linking my arm in his:

“There is nothing which can be done yet awhile; we must loiter around until night has come, and if so be the man who is in hiding has as much sense and quick wit as a spy needs, then will he understand that we are forced to wait until the hue and cry has died away before we can venture a hand to save him.”

Well, Jeremy had no reply to make to this, and for the very good reason that there was nothing he could say.

He knew as well as I, that for us to approach the hiding place of the stranger now, while the lobster-backs were so near at hand and so likely to come into the yard, would be much the same as delivering the fellow over to death, therefore he followed my lead, and we two walked as slowly away as if there was nothing whatsoever on our minds save a desire for pleasure, toward the Jolly Tar inn, where there was good reason to believe we might meet with some of our comrades.

It can well be supposed that we discussed this sudden change in our affairs most earnestly as we walked along; but without arriving at any very satisfactory conclusion. We had most like saved the life of a man that day, and the question which would come into our minds, despite all efforts to banish it, was whether or no we might succeed yet further in the purpose, or if that which we had done was only to keep him on this earth a few hours longer.

[23]Certain it was, once the Britishers suspected him of being a spy, he would suffer the death of one in event of being captured, for the lobster-backs were not overly careful about spilling the blood of Americans.

Now you must know that our boat lay hidden on the bank of Dock creek, under a pile of lumber and general building material, where, save strictest search was made, she would be undiscovered by the enemy.

It is not to be supposed that at this time we boys had very much opportunity to indulge in boating. The British ships lay so thickly at anchor in the river off the town that, as Jeremy said, one might not safely pass a knife-blade between them, and unless we were minded to go up stream, where was every chance of being overhauled by one of the guard-boats at the expense of losing our craft, we were forced to content ourselves with looking at her now and then, thinking with a deal of satisfaction that we had succeeded thus far in holding that which his high mightiness, General Howe, insisted we of Philadelphia should not be allowed to keep in our possession.

The Jolly Rover was the name of our boat, and she was not very much to look upon with pleasure, being nothing more than a skiff, as you might say, with the forward part decked in, so that we might venture down toward the Capes even in stormy weather, without risk of being swamped.

However, to us she was as valuable, and, perhaps, as seemly looking as any of his majesty’s vessels, and it appeared to me that after having crawled beneath the lumber to get at her, knowing the lobster-backs were supposed to keep a strict[24] guard nearby, I could better think out any problem which presented itself to my mind, because of being, so to speak, under my own vine and fig tree.

Therefore it was that I led Jeremy down toward Dock creek, turning over and over again in my mind, as you may well suppose, the chances for and against our being able to aid that stranger who, if he acted the truth, and I doubted it not, was laboring for the American Cause and now had none on this earth to trust in save us.

It seemed like the rarest stroke of good fortune that we should chance to come upon young Chris, meaning Chris Ludwig, son of Christopher Ludwig, the baker, who was our especial crony, and also an equal owner in the Jolly Rover.

Young Chris was loitering around Front street nearabout the creek, having nothing especial to do, for if there was one thing in this world that he was unfriendly with it was work, and although his father stood ready at all times, almost too ready, the lad said, to give him employment, he did his best to evade it. On this day verily I blessed his indolence, for, with the exception of Jeremy, he was the one person in Philadelphia to whom I could open my heart without fear of being betrayed.

One might suppose that a sensible lad would go at once to his father with such information as was in my possession—dangerous information;—but I had none to whom I could appeal. My father had long since been dead; my mother was a widow who, with what little aid I could give her by earning a shilling or a sixpence now and then, eked out a livelihood letting rooms in the house where I was born, therefore this taking possession of the city by General Howe was not unwelcome to her in[25] one sense, although she was as good a “rebel” as could be found in all our colony of Pennsylvania.

British officers were inclined to spend the king’s gold whenever there was an opportunity of ministering to their pleasure, and many of them hired apartments in the city rather than be quartered wheresoever their billets led them. Thus it was that we had in my home three lobster-backs, all officers of the Royal Irish regiment, and you can guess that I heard every day of my life such threats or suggestions against us of Philadelphia as made my blood boil, although I dared not speak a word in protest, else had I gone to the stone jail, or to join the prisoners in the state house, without delay.

As a matter of course, young Chris was eager to know where we had been and what was our purpose at present; but although there were none in the streets nearby who might overhear my words, I refused to make any explanation whatsoever until we were in our snug hiding place beneath the lumber pile, and so told him, speaking in such a tone that on the instant he understood something of great import must be in the wind.

It required no less than half an hour of skilful manœuvring for us to get on board the Jolly Rover, safely hidden beneath the overhanging timbers, for we were forced to go one at a time lest, otherwise, undue attention be attracted to our movements.

But finally we were on board the craft, and then it was, sparing not words so that the lad might have full knowledge of all which had occurred during the morning, I told young Chris of our situation as it concerned the stranger.

One might have thought the lad would have been overwhelmed with fear at the bare idea of harboring[26] a spy, for in our city of Philadelphia in the year of grace 1778, to do so was such a crime as the lobster-backs would never overlook until one had danced at the end of a rope so long as life remained in his body.

But Chris was not of that stamp. Instead of showing fear, it pleased him seemingly to a great extent that we had been able to do even so much as hide the spy, and straightway, without thinking of the danger, he began speculating as to how we might aid the stranger.

“I am ready to take the chances of setting off with him in this boat during the night, going so far up the river that he may be able to get on shore without being observed, for, of course, it is impossible we could make our way below the city past all the ships-of-war on which strict watch is kept.”

“It strikes me that we should first learn where the man comes from,” Jeremy interrupted. “Certain it is he ventured into this city on important business, otherwise he never would have risked his neck so rashly, and it is for us to learn how his work may be furthered, rather than say we will do this or do that because it best suits our convenience.”

“Very well,” young Chris said quickly. “What is to prevent us from knowing exactly how he would have us lend him a hand?”

“In order to do that, we must have speech with him,” I replied quickly, “and, moreover, there is a possibility the man stands in need of food.”

Young Chris made a gesture with his hand as if to say I was talking at random, and cried incautiously loud:

[27]“What is to prevent your having speech with the man, and that right speedily? As soon as night has come I will take my station at Black Horse alley to give warning if any of the lobster-backs approach that way. Jeremy shall stand guard at the gate on Chestnut street, and then you, Richard Salter, may go in and talk to the man to your heart’s content, so that you do not give the lobster-backs an inkling of your purpose before having entered the shop-yard.”

Strange as it may seem, this simple plan had not occurred to me; I had fancied it would cost us a deal of trouble and could be done only at the expense of much danger, yet the moment young Chris had spoken I understood how simple it would all be, providing the lobster-backs were not loitering in the neighborhood, suspecting the man might be hidden nearby.

However, I was not minded that the lad should believe he had contrived something which had escaped my attention, and therefore said, much as if it had been my purpose all the while to do this same thing:

“Of course, that is what must be done. The question in my mind, however, is whether the man still remains where we last saw him.”

“How could he go elsewhere?” young Chris asked sharply. “He has no means of knowing but that the Britishers are close about waiting for him to come out, and because you gave him the hint where a hiding place might be found, he will depend upon you to aid him farther, unless he be a veritable simple.”

Well, we discussed the matter, each in turn suggesting the most improbable methods of getting the[28] stranger out of the city, and arriving at no satisfactory conclusion. It seemed well-nigh impossible we might thus pluck a spy from out the clutches of the Britishers without bringing ourselves to the gallows.

You must understand that in this year of grace 1778, we of Philadelphia were lying, as one might say, bound hand and foot at the mercy of those whom the king had sent to whip us into subjection; and at the first move man, woman, or child might make toward doing anything in aid of their distressed country, then was punishment severe and terrible to think upon, sure to follow.

Of course, we could do nothing toward aiding the spy until night had come, and so excited were we all that there was no thought in the minds of any that we might be needing food; but it seemed almost as if the safety of the man depended entirely on our remaining aboard the Jolly Rover, hidden from view, until the favorable moment when we might take steps in his behalf.

I knew full well my mother would be anxious regarding me if I failed to return home at the accustomed time, and yet it seemed that I must stay there, if indeed I gave much of any heed to such fact. I was so puffed up with the idea that it might be possible for me to do something which would give me an enviable name among those who were serving the colonies, that it was as if I had no home nor anyone who would be concerned whether I came or remained away.

Young Chris had no desire to go back to the bakery even for a few moments, because he knew full well that his father would find some task for him to do, therefore was he content to remain[29] with me. Jeremy Hapgood, however, had better sense than either of us, for he understood he ought to report himself at home at least once during the day, and, finding that we were not disposed to come out from our hiding place until it was sufficiently dark to carry into execution the plans we had formed, he set off alone, counting to relieve his mother’s anxiety, if so be she felt any concerning him, which was exactly what both young Chris and I should have had manhood enough to do.

There is no good reason why I should set down all that was said by my comrade and me while Jeremy was away, for we talked much that was foolish, I dare venture to say. Nor were we in any way disgruntled as Jeremy crept under the lumber pile, when the afternoon was nearly half spent, his pockets bulging with food which he had brought for us, he being a thoughtful lad where the comfort of his friends was concerned.

While we ate greedily, for to tell the truth both of us were anhungered, he gave us the pleasing information that no Britishers were to be seen in the vicinity of where the stranger was hidden.

It appeared surely as if the lobster-backs had come to believe that the spy made his way up Chestnut street, or sought refuge in some of the buildings there, rather than nearabout the coffee-house, and, as Jeremy said with a chuckle of satisfaction, matters were shaping themselves much as we would desire.

Jeremy had sufficient good sense to loiter around the London Coffee-House amid the throng of officers which frequented that place, hoping he might hear somewhat concerning the events of the forenoon, and in this he was not disappointed.

[30]The lobster-backs, it seemed, were discussing over their ale whether the man who had been chased was indeed a spy, or some witless creature, as one of them put it, who had inadvertently said that which caused suspicion to fall upon him.

It appears that the man had been in the coffee-house seemingly for the sole purpose of taking refreshment; but, so one of the Britishers declared, keeping his ears open to all that was said around him.

Now it so chanced that one of the high and mighty lobster-backs who sported a sword, had proposed in a drunken spirit that all within the room should drink to the health of the king, and this man was so slow in responding, that instantly the Britisher asked him if he was for the king or for the colonies.

Now why it was, the man having come into Philadelphia as a spy, if indeed such had been the case, he should have hesitated to give the proper answer, I failed to understand, nor could Jeremy learn very much regarding the particulars of what occurred just at that moment. At all events, the stranger was immediately accused of being a spy, and when he indignantly denied it, was asked to go to headquarters that he might explain his business and tell why he was in Philadelphia at that time, if indeed he did not live in the city.

Without making reply to this suggestion, the man leaped to his feet, counting to trust to his heels rather than his tongue to get him out of the scrape. Whereupon, every red-coat customer in the coffee-house set chase after him, crying out as we had heard.

[31]According to Jeremy’s story, the Britishers were not greatly disturbed regarding the possibility that a spy from the American army had been among them. They rather took it for granted that the man was of no especial importance; that he could do them no harm, since nothing of a private nature had been discussed in the coffee-house. Because the farmers were allowed to come in from the country nearabout to sell their produce, it was not strange that one of them, and this man was seemingly a farmer by his garb, should be friendly to the colonies to such an extent as to hesitate about drinking the king’s health.

All this was in favor, as a matter of course, of the man whom we had set out to befriend, for it told that there would not be a very strict watch kept over those who might attempt to leave the city, and again we knew, or believed we did, that there would be no especial guard stationed nearabout where the man had disappeared.

“It is all as plain sailing as a fellow could wish,” young Chris said in a tone of satisfaction when Jeremy was come to an end of his story. “The British are here in such numbers, while our army is penned up in Valley Forge seemingly unable to make a move, that General Howe’s officers do not fancy any danger can come to them from us rebels; therefore we have simply to carry out my plan of gaining speech with your friend the spy as soon as night has come, and you may set it down as certain, Richard Salter, that you will not be disturbed however long the conversation may be between you and the man. However, I would recommend that you put a stopper to your[32] tongue in decent time, discussing how it is possible for him to get out of the city, rather than striving to gratify your curiosity.”

Young Chris’s remarks rather nettled me, although I would not allow him to see it. I was a year his elder, and although I had done nothing which gave proof of my ability to serve the colonies, I counted that I was quite as able to conduct an affair of this kind, dangerous though it was, as he, and preferred in my folly to be looked on as the leader in this enterprise, rather than as one who must obey the command of others.

Therefore it was that I failed to make reply to his remark, and Jeremy was tired of talking, consequently we three fell silent, crouching in the Jolly Rover beneath the overhanging timbers until the sun went down, and darkness covered Dock creek even as it covered Philadelphia.

The night had come. There was no longer reason for us to hesitate or to linger, for we were only counting on darkness to favor us, rather than the lateness of the hour, and after assuring myself the coast was clear, by creeping out amid the timbers where I could have a fairly good view of the surroundings, I said in a whisper to Jeremy and young Chris that the time had come for us to make an attempt at gaining speech with the stranger.

If General Howe himself had been striving to make matters easy for us in the attempt to visit the spy, matters could not have gone more to our satisfaction.

Singularly enough, we failed to meet with a single squad of red-coats as we came up from Dock creek to Black Horse alley, and having arrived there, could see no one in the immediate vicinity.

At the London Coffee-House, just outside the doors, were mayhap half a dozen officers loitering as if waiting for some friend; but that gave me no concern, for those who held commissions in his majesty’s army did not stoop to do such work as hunting down a spy, because there were plenty of the rank and file to whom they could detail anything which was disagreeable or laborious.

Therefore it was that we marched directly into the yard, taking fairly good care, however, not to make any great display of ourselves. Having come to the gate which led on Chestnut street, Jeremy went outside after we had decided that if either he or young Chris should see anything which was of a suspicious nature, they should give the alarm by each shouting the other’s name, afterward making their way without delay to the Jolly Rover where, if so be I was not interfered with, I could meet them.

Then it was that young Chris went back to the entrance of Black Horse alley, and I was left alone[34] in the yard to seek out the man whom I had undertaken to befriend, even though he had not called upon me for such service.

I had marked well the place where he disappeared amid the decaying timbers, and, lying at full length, I forced my body beneath the rotten lumber until I was well inside the covering, when I called in a whisper:

“Hello there! I am the lad who lent you a hand this morning!”

While one might have counted ten there was no answer to my call, and not until I had repeated it twice did I hear anything betokening the man’s whereabouts.

I was almost come to believe he had taken matters into his own hands, and, rather than trust to boys, had set about making his way out of the city. It was even when I was on the point of backing out from the uncomfortable hiding place that I heard a movement beyond me in advance, and then came a cautious whisper.

“Is there no danger in my coming out?”

“None so long as you remain quiet and are ready to take to cover again at the first alarm,” I replied, and before the words were hardly out of my mouth, the man was so near that by stretching forth my hand I could touch him.

“Are they searching for me?” was his first question.

I replied to it by telling him all Jeremy had learned during the afternoon, whereupon he asked, as if even at this late hour there was some little distrust in his mind regarding my honesty of purpose in striving to aid him:

[35]“Who are you, lad?”

“Richard Salter, son of that widow who lives in Drinker’s alley, and, while the lobster-backs are here in Philadelphia, gains a livelihood by letting to them such rooms in our house as we do not occupy.”

“There was another lad with you this morning?” he said in a questioning tone, and I replied promptly:

“Ay, that was Jeremy Hapgood; but now there is a third fellow who would strive to save you from the halter.”

“And who may that be?”

“Young Chris, son of Christopher Ludwig the baker.”

“Ah, Ludwig the baker; then surely that lad should be trusted,” the stranger said, and in such a tone as nettled me, whereupon I cried incautiously loud, speaking sharply:

“There are none of us three who may fairly be suspected of doing aught save that which is for the good of the Cause, else would we have left you this morning to the mercies of the lobster-backs. If peradventure one of them had suspected that I was seeking to show you a hiding place, then would my shrift have been short indeed. In case you are acquainted here in Philadelphia, you know where I must of necessity have been at this moment if so be they got any hold upon me.”

“Ay, ay, lad, I understand all that, and you must forgive me even for seeming to question your honesty; but when a man is as I am, lying ’twixt the halter and a bullet, it is not to be wondered that he questions everyone around him, even those[36] who are seemingly doing what they may to lend him aid.”

“Never mind that part of it,” I interrupted hastily, ashamed of having given rein to my tongue at such a time. “I know not whether it may be possible for us lads to help you out of this scrape; but surely it seems to me we might do almost as much as men, since boys are not so likely to be suspected by the lobster-backs as those who are older grown.”

“You may do as much as men, and even more, lad. Have you boys here in Philadelphia who love the Cause, no association such as the Boys of Liberty in Boston, or the Minute Boys in other colonies?”

“There is little chance we could have,” I said with a laugh in which was no mirth. “Perhaps you do not know how closely we are watched by the lobster-backs.”

“I dare venture to say you are in no worse condition than are other lads who, binding themselves together with the agreement to do whatsoever they may in aid of the colonies, have already succeeded in accomplishing very much. How many are there of your age, or thereabouts, in this city who may be trusted?”

Hurriedly I ran over in my mind those whom I knew to have favored the Cause, and said at random:

“A dozen mayhap. There possibly are more; but I do not now recall others with whom I would be willing to trust my liberty or my life. But do you really think boys no older than thirteen or fourteen years might aid the Cause?”

[37]“Ay, of a verity I do, my lad. Are you not even now doing that which many a man who claims to be a true son of the colonies, would flinch at? To aid a spy in his escape is no slight crime in the eyes of those who serve the king.”

“But this was something which happened unexpectedly,” I replied, “and we would not find a like opportunity again in a lifetime, I might almost say.”

“Ay; but if you and your friends sought for the opportunity, my lad, you could do very much, and particularly just at this time,” the man said earnestly, as if it was of the utmost importance that he interest me in this matter, and his eagerness surprised me not a little. “With a dozen lads who were ready to do whatsoever they might, the work of men like me, who venture into the enemy’s camp, might be lessened very greatly, and information sent out which could not otherwise be had by our people,” the man continued, now with his lips close to my ear lest any might overhear.

“Tell me how it could be done?” I cried eagerly, now burning with the desire to do something which should give me a name among those who were struggling to throw off the yoke of the king, for until this moment I had not believed it possible lads like myself would be able to accomplish anything of importance.

“Suppose I wanted to send word to Valley Forge, or to Swede’s Ford, or anywhere else you please, of what I have learned in this city, and yet desired to remain here longer in order to gather more information? How well you lads could serve the Cause by carrying such message—”

[38]“Do you mean to General Washington?” I cried excitedly, now raising my voice so that the man laid his hand on my lips as he replied:

“Ay, to him, or to any other officer who might be waiting for the information. In fact, lad, there is no need why I should go into detail with you, explaining how a company of boys could aid the colonies here in Philadelphia, even as they have aided them elsewhere since this war for independence began. Instead of discussing that matter now, let us set about, if so be it is in our power, to say how I may get away from the city without loss of time?”

“And where would you go, sir?” I asked.

“Anywhere outside the British lines. My purpose is to reach Swede’s Ford within four and twenty hours.”

“Would you take the chances of going down the river as far as the mouth of the Schuylkill, in a small boat which is hardly more than a skiff?” I asked, and then told him of the Jolly Rover, whereupon he remained silent while one could have counted twenty, after which he said hesitatingly:

“I question much, lad, whether it would not be easier to get away by land rather than water, for from what I have seen, the lobster-backs are keeping close guard over the river.”

“Ay, over the Delaware, but not the Schuylkill, and if Swede’s Ford be the point you aim at, then it behooves you to go up the Schuylkill. I dare venture to promise that we could get the Jolly Rover out from beneath the lumber pile twixt now and midnight without any lobster-back being the wiser.”

[39]“Do you think I might dare venture out within an hour, say?” the man asked, and I replied, without hesitation:

“If so be you go with us, and make a move only when we give the word, allowing that you are my uncle, or cousin, or whatsoever blood kin you may choose to say in event of our being overhauled, then do I believe we might start this moment.”

He showed himself inquisitive as to my plans, and I surely could make no complaint as to that, for the man was giving his life, so to speak, into my hands, and one could well fancy he would be curious to know whom he was thus trusting.

The result of all his questions and my answers was, that within five minutes I backed out from beneath the decaying timbers, ran to the entrance of Black Horse alley, and in the fewest possible words told young Chris what we were about to do, asking his opinion.

He felt quite as confident as I, that at this hour in the night we might safely make the venture, and after telling me to bring my spy out into the open, he ran to warn Jeremy that it was no longer necessary for him to remain on duty at the gate.

The stranger came promptly out at my bidding, and when he was standing in the yard, while we were waiting for young Chris and Jeremy to give the word that the coast was clear, I whispered warningly:

“If so be we come upon a squad of lobster-backs who are inclined to question us, it may be as well that you should claim to be my uncle who has come down from Germantown.”

[40]“And have you an uncle in Germantown, lad?” the man asked.

“Indeed I have not; but what concern might that be of yours?”

“Only this, my boy, that if you had one who lived in Germantown, and I should afterward come to grief, it might be the worse for him that you had used his name.”

It pleased me not a little that the man should be thus careful for my safety, or for the safety of those who were near to me, and although I had had no distrust of him before, I felt every confidence from this on.

We lost no time, after young Chris had signaled that the coast was clear, in setting out from the shop-yard on the way to Dock creek; but you may be very certain that we kept strict watch ahead and behind, lest we should come upon, or be overtaken by, those whose duty it was to make certain that “rebels” were not abroad after the sun had set.

Now it may seem like some fanciful tale, rather than reality, that we could thus walk boldly abroad in the evening when the lobster-backs were supposed to be on the lookout for everyone who was not of their kidney.

But it must be borne in mind that General Howe had long held possession of the city; that he had come to believe the American army was powerless to do anything against him; that he felt confident the people of Philadelphia would not dare make any attempt in their own behalf, and, in addition to all this, his men, officers as well as privates, had really grown careless, or I might say, lazy. They no longer were so keen to search out rebels, because it might take them from their pleasures, and verily the king’s men in our colony at this time were living a life of ease and of indolence.

WE KEPT STRICT WATCH AHEAD AND BEHIND.

[41]Much of what I have just set down was said to me by the stranger as we walked, now in a group, and again stretched out in single file that we might the better guard against an approach of the enemy. And he spoke thus in order to let me understand that it was not difficult, if a man was willing to take his life in his hands, to play the spy upon General Howe’s army.

“There is no reason why I should try to make you believe, lad, that this work of spying upon the red-coats is a simple matter, for hardly twelve hours are gone since you saw me fleeing for my life. That, however, was due to my own carelessness; but if a man so chooses, he may come into this city of Philadelphia and remain day in and day out without being questioned. It is the possibility of sending away his report, if so be he has one to make, which oftentimes puzzles him, and therefore was it that I spoke of you lads binding yourselves together here as Minute Boys, following the example of those in other colonies.”

“What’s that? What’s that?” young Chris asked jealously, and the stranger, understanding that we must not hold overly much converse on the street, made reply by saying:

“It was a suggestion which I made to your comrade, and when we are where we can hold converse without danger of being overheard, or of running our necks into a noose, I will explain to you what I have broached to him.”

Young Chris would have insisted upon knowing then and there all that had been said between the[42] stranger and myself; but Jeremy interrupted him by whispering sharply:

“I am not minded to linger here on the street in such company, even though it be your pleasure! Our affair is to get this man hidden in the Jolly Rover until he decides how he will leave the city, and until he has gone I’d have you bear strictly in mind, young Chris, that we are not to take more risks than may be absolutely necessary.”

At another time and in another place, perhaps, young Chris would have made some sharp reply, for he was not overly patient when there was a suspicion of reproach. But just at this moment he understood, even as well as we, that he could not afford to be thin-skinned whatever might be said, and from then on there was no further need to urge him to move swiftly toward Dock creek, until we were come within sight of the lumber pile, when the four of us halted to make certain there were no prying eyes nearabout.

“The coast is clear,” Jeremy said thirty seconds later.

And then, without hesitation, he led us to our hiding place, we following close at his heels.

Once we were concealed beneath the lumber pile, I said to myself that this was good token we would succeed in whatsoever was our purpose, for if we could come from Black Horse alley in company with the man who had but so lately been chased as a spy, and gain our place of refuge without any hindrance, then were we likely to make names for ourselves as Minute Boys.

Even while we were crawling beneath the timbers, did I repeat to myself the words “The Minute Boys of Philadelphia,” and they had a pleasing ring[43] in my ears, for once we had banded ourselves together in such a company, and were given by the leaders of the American army work to do, then might we count ourselves as being well in the forefront of those who would free the colonies.

“It was easily done,” young Chris said when the four of us were on board the Jolly Rover, and he spoke much as though he alone and unaided had brought all this thing about. “Now let us hear what it was you and Richard Salter had to say that was seemingly of importance,” he added to the stranger.

Whereupon the man, and I could fancy he was smiling, although owing to the darkness it was impossible to see his face, because young Chris’ tone was so high and mighty, began in a low tone:

“In the first place let me tell you who I am. My name is Josiah Dingley, and I did live at Germantown in that house next the Lutheran church, before the battle; but after that bloody day I cast my lines in with those who were struggling against the king, having been lukewarm in the Cause until then. Because of knowing this city well, I was sent here near to two weeks ago, and I believe the purpose of my visit was to prepare the way for some move which will shortly be made by our people at Valley Forge.”

“And have you been in Philadelphia all that time?” Jeremy asked in surprise.

“Nay, lad, I have twice been to Valley Forge, and was but lately returned when you came upon me.”

“And have you learned anything of importance in all that while?” I made bold to ask, whereupon the man replied quickly:

[44]“That is not for me to say, lad. I have come upon certain things which were set me to learn; but further than that I must not speak. Now it is of importance that some other take my place, for after having played the simple in the London Coffee-House, I must expect to be recognized if so be I should chance to come upon those lobster-backs who were there at that time. I have been thinking over your proposition that I go out from the city by means of this skiff, and I am more than inclined to believe it might be done.”

“But first let us hear what it was, Master Dingley, that you had to say to Richard while you two were in the shop-yard?” young Chris interrupted, and the spy replied:

“I will leave that for your comrade to tell you later. Just now it behooves me to speak of other matters. Are you lads still of the mind to take the chances of pulling down the Delaware in this craft?”

“Indeed we are,” I replied stoutly. “If so be you will take the risk for yourself, we lads will chance it on our part, and I dare venture to say that between now and daylight we shall not only have carried you to some point beyond the British lines; but be back here with the skiff safely hidden once more. The watch which the lobster-backs have been keeping over us rebels of late is not as sharp as it might be.”

Now it may seem to some as if I spoke at random in thus declaring that we could go out from our hiding place, run down the Delaware, and then up the Schuylkill river so far as this man might want to go, while the Britishers claimed that they kept sharp guard over both rivers.

[45]It would seem at first sight almost impossible, and yet we lads had come to know the movements of the guard-boats so well that unless something unforeseen took place, we might venture to state positively where this or that patrol would be at a given time.

I am not minded to make it appear as if there was no danger in the enterprise, for surely there was, and in plenty.

If it should so chance that we lads were taken while we had Master Dingley on board, and he was shown later to be the same man who had been chased out of the London Coffee-House, then might we reasonably expect to share the same fate as his, and all know what a spy meets with when he has been taken within an enemy’s lines.

In addition to that, if after we had landed the man we were overhauled by the Britishers, then would it be indeed difficult for us to explain why we were abroad at that time of the night, for I am of the opinion that neither Lord Howe, nor any of his officers, would accept as excuse for us the fact that we were eager to go boating, and had simply hit by chance upon such an hour.

Whether the odds were in our favor or against us, however, the die was cast, as you might say, when we had made the proposition that we would take Master Dingley away.

And now that he much the same as declared his willingness, as well as his desire, that we should carry out that which was the same as a promise, it behooved us to make ready for the enterprise in such manner as if believing we might come to grief before it was ended.

In order to do this it was necessary we send[46] some word to our people at home, for while we might excuse ourselves because of having remained away so long without announcing an intended absence, it would be little less than cruelty to keep silence until morning, since all three of us knew full well how deeply our mothers would mourn, believing we had come into some trouble with the hirelings of the king who were ever so ready to get us rebels on the hip.

There was no good reason why all should go out on such an errand, and therefore it was I proposed that we cast lots to see who should be the messenger.

To this young Chris made decided objections. He declared it was his intention to know what secrets Master Dingley and I talked while we were hidden in the old stable back of the shop off Black Horse alley, and if so be the lot fell on him to carry word to our parents, then would he miss the chance of gaining what he believed was valuable information.

I was truly vexed with the lad because of his obstinacy, and for bringing up such a trifling matter at a time when we were engaged in work of grave import; but, luckily, before I could utter those angry words which were already in my mouth, Jeremy said:

“I am well content to hear what Richard and Master Dingley may have to tell us, at some later day, therefore, young Chris, if you are determined the story must be told you at once, I will take it upon myself to warn our people that we may be away from home mayhap four and twenty hours.”

“Why make it such a long time?” young Chris asked grumblingly. “There is no question but[47] that we shall be back by daylight if we come at all—”

“Do not speak so rashly, my young friend,” Master Dingley said gravely. “There may be very many good reasons why it would be safer for you to remain away from home eight and forty hours, or even longer, than to return at once, therefore let your people know exactly what you are about, and how many are the chances against your returning soon.”

Jeremy did not wait for any discussion on this point, but without further delay started from amid the timbers to gain the outer air, which was a work of no little time owing to the fact that he must first assure himself the coast was clear before going into the open.

Young Chris and I, who had so often done that which Jeremy was now doing, gave little heed to his movements, save as a matter of course that we kept our ears open to hear any token of a mishap, and after waiting two or three minutes, at the end of which time we could safely calculate Jeremy was speeding on his way, young Chris said in a peremptory tone:

“Now, if it please you, Richard Salter, we will hear what that great secret is between you and Master Dingley.”

“It is no secret whatsoever, and a matter that could better have been told you to-morrow, or the next day, than now. But since you are so greedy for the information, and so jealous lest something had been said of which you are not fully informed, I will explain the matter.”

Then it was that I told the lad what Master Dingley had said regarding our forming a certain[48] number of Philadelphia lads into a company of Minute Boys, and straightway the baker’s son was in an ecstasy of joy.

It was to him a most happy idea, for Chris delights in being at the head of whatever may be going on, and this enrolling himself as one of the colony’s defenders, even though he might not be able to serve her to advantage, was much to his liking.

Without stopping to consider the matter, he declared stoutly that we could enroll no less than twenty lads in such a company, all of whom would be ready to do whatsoever they might be called upon, and while he was thus telling what a simple matter it would be, Master Dingley interrupted him by saying gravely:

“Be cautious, lad. Remember that whomsoever you shall ask to join in such an enterprise much the same as holds your life in his hands, and make certain before you speak one word of your secret, that he to whom you are talking may be trusted so long as life remains in his body.”

“I will answer for all of those lads whom I have in mind,” young Chris replied carelessly, and I fancied that Master Dingley made a gesture of impatience, for this matter which might turn so seriously for all concerned, was being treated altogether too lightly by young Chris.

It behooved him, as well as all of us who were minded to join in the enterprise, to realize fully with what danger it was attended. If we formed the company, it should be with the knowledge that our lives might pay the penalty, for if so be we were taken while carrying information out of the[49] city, or bringing it in, then was it certain we would end our days on the scaffold.

It was as if Master Dingley understood that it would be useless to argue with young Chris while he was so excited, and therefore held his peace, as did I, while the baker’s son continued to name lad after lad whom he would urge to become Minute Boys, many of whom I knew had a leaning toward the king, or, if they failed to have any decided opinions themselves, came of such rabid Tory stock that we could not afford to give up our secret to them.

However, it matters little what I thought, or what young Chris said just then. The work in hand was to carry Master Dingley beyond the British lines, and in the doing of it we might meet with such misadventure that there would be no Minute Boy business for us in this world.

After a time young Chris grew weary with carrying on a conversation in which neither the spy nor I joined, and during mayhap half an hour we sat there silently in the Jolly Rover, hearing now and then the tramp of the lobster-backs as they marched too and fro in squads to make certain we rebels of Philadelphia were not plotting against the king, when came sounds from outside which told that Jeremy was returning.

An instant later he was beside me, panting heavily as evidence that he had been running at full speed, and unable for the moment to speak.

“Well?” young Chris asked impatiently, “have you seen all our people?”

“Yes,” Jeremy panted, “and none of them favored our going away.”

[50]“Did my mother order me to return home?” I asked anxiously, and by this time Jeremy had so far regained his breath that it was possible to speak.

“She did not say you must come, but it was easy to understand her desire you should do so, and when I said that we had committed ourselves to aiding Master Dingley, she held her peace, but looked mightily discontented.”

“It is not my purpose, lad, to insist upon your carrying out the promise made, for I understand full well how dangerous it may be, if your parents are unwilling you should make the venture,” the spy interrupted. “You have already done me a good turn, and if peradventure you believe it your duty to stay here, then shall I go my way as best may be, feeling that you lads have saved my life for a time, at all events. If it is sacrificed now, it will be through no fault of yours.”

“We will go as was agreed,” young Chris cried impatiently. “I have no doubt but that father would like to have me stay with him in order to help in the bakery, but when work like this can be done by us lads, we must not think about what those at home may have to say regarding it.”

“That is where you make a grievous mistake, my lad,” Master Dingley said gravely. “Your first duty is toward your parents; then shall come the colony, if you please. But until you are men grown, remember that the only safe plan is to act as your mother, who surely is a lad’s best friend, would have you.”

“There is no question in my mind whatsoever but that if we were this moment in our homes, and should state exactly what had occurred during the[51] day, there would be no protest made against our going with you, sir,” I interrupted, determined that whether we formed a company of Minute Boys or not, I would have a hand in this saving of a human life, at the same time that we got the best of the lobster-backs.

“It shall be as you say, lads, although my mind would be easier if you went with your parents’ consent. Now when shall we set out?” the spy asked in a low tone, whereupon I replied, before young Chris had an opportunity:

“At once. There is no reason why we should make delay, save to be certain the river is clear, and then I propose that we creep down within the shadow of the bank until we are a goodly distance from here, after which, unless matters have changed greatly of late, we shall, I believe, be beyond the point of danger.”

Without waiting for the word, Jeremy crept out toward the water’s edge where was an overhanging plank that afforded us a famous resting place while we spied upon the lobster-backs, and within five minutes he came back, giving us the welcome information that there was no guard-boat in sight.

After that we lost no time. There were few preparations to make, save that of pushing the skiff out from beneath the timbers, which was a task requiring considerable strength, because we were forced to tip her first this way and then that, in order to avoid the planks which ran on either side considerably nearer the water than her height would admit of passage.

In this work Master Dingley aided us not a little, and within mayhap fifteen minutes from the time[52] Jeremy had come back, we were out of the hiding place, creeping cautiously well within the shadow of the right-hand shore as we started on the dangerous enterprise.

Save for the twinkling of the lights from the fleet, and the hum of voices which came to us from over the water as the sailors lounged around the decks of the war vessels talking, there were no signs of life.

Shoreward, in our immediate vicinity, it was dark as a negro’s pocket, with never a sound betokening the presence of human beings, and Jeremy whispered in my ear as we two worked one oar while Master Dingley and young Chris worked the other, that it was a good token we had got away thus readily.

I nervously bade him hold his peace. Until we were really committed to the work, I had failed to realize all the dangers, but now that we were afloat where the lobster-backs might come upon us at any moment, my heart began to fail me.

While I would not have turned back now that my hand was on the plow, so to speak, it would have pleased me wondrously if we had never come across Master Dingley, however eager I was to do whatsoever lay in my power to aid the colonies.

If we could go out with the soldiers and stand up in manly fashion against the Britishers, then might I be proud; but this aiding a spy, with a shameful death before us if we were captured, was something to make the cold chills of fear run up and down a fellow’s spine.

However, we were embarked in the enterprise, and it stood me in hand to do whatsoever I might[53] toward making it a success, because of the price which failure would cost.

There was little we could do just then, save to row as swiftly as was consistent with silence, for we dared not lift the oars so that any noise might be made, because, as everyone knows, the water carries sound a long distance, and even while hidden from view, we might betray our whereabouts through carelessness.

We were forced to keep on down the river in order to come to the mouth of the Schuylkill, and in so doing must pass all the king’s ships. If peradventure some officer was putting off from the Philadelphia side to go to his vessel, and we were come just at that time nearabout his course, then were we in danger.

You can well fancy, as we neared the huge craft, with what caution we worked the oars. It was as if I hardly dared to breathe; as though the sound of my heart-beats would give the alarm, and before we were five minutes on our way I was dripping with perspiration, caused, I am free to confess, by fear, while I was almost as wet as if I had gone over the skiff into the water.

I have talked later with lads who claimed that it was impossible the smallest skiff could make her way, even during the darkest night, past all that fleet where it was reasonable to suppose the sharpest of sharp watch was kept; but yet that we did, going our course without being hailed by man or boy, by lobster-back or patriot.

If we had had the power to direct events according to our own pleasure, matters could not have worked more favorably for us, because, as I now[54] look back upon that short voyage, it seems to me almost beyond belief that we could have done what we did without bringing about our ears a very nest of red-backed hornets.

Now in order that you may know how the lobster-backs guarded our city of Philadelphia, and what danger we lads were running our noses into, I count to set down here that which I have read within the week, and it was written by one who has seen it drawn out in clerkly fashion on a map belonging to General Howe.

“The line of intrenchments from the Delaware to the Schuylkill extended from the mouth of the creek just above Willow street to the upper ferry on the Schuylkill. They consisted of ten redoubts connected by strong palisades. The first redoubt, which was garrisoned by the Queen’s Rangers under Simcoe, was near the forks of the roads leading to Frankford and Kensington. The second redoubt was a little west of North Second and Noble streets; the third between North Fifth and Sixth and Noble and Buttonwood streets; the fourth on Eighth street between Noble and Buttonwood; the fifth on Tenth between Buttonwood and Pleasant; the sixth on Buttonwood between Thirteenth and North Broad; the seventh on North Schuylkill Eighth between Pennsylvania avenue and Hamilton street; the eighth on North Schuylkill Fifth and Pennsylvania avenue; the ninth on North Schuylkill Second near Callowhill street, and the tenth on the bank of the Schuylkill at the upper ferry.

“The encampment extended westward from North Fifth, between Vine and Callowhill, as far as North Schuylkill Second. The Hessian grenadiers[55] were encamped between Callowhill, Noble, Fifth and Seventh streets. The Fourth, Fortieth and Fifty-fifth British grenadiers, and a body of fusileers, were on the north side of Callowhill, between Seventh and Fourteenth streets. Eight regiments lay upon the high ground around Bush’s hill, extending from Fourteenth, nearly on a line with Vine, to the upper ferry.

“Near the redoubt at the Ferry was another body of Hessians. The Yagers, horse and foot, were encamped upon that hill near the corner of North Schuylkill, Front and Pennsylvania avenue. On the Ridge Road near Thirteenth street, and on Eighth, near Green, were corps of infantry. Light dragoons and three regiments of infantry were posted near the pond between Vine, Race, North Eighth and Twelfth streets. A little below the middle ferry, at the foot of Chestnut street, was a fascine redoubt, and near it the Seventy-first regiment was encamped. Some Yagers were stationed at the Point House opposite Gloucester.

“When winter set in, many of the troops and all the officers, occupied the public buildings and houses of the inhabitants, also the British barracks in the Northern Liberties. The artillery were quartered in Chestnut street between Third and Sixth street, and the State House yard was made a park for their use. During the winter, General Howe occupied a house on High street where Washington afterwards resided; his brother, Lord Howe, lived in Chestnut street; General Knyphausen lived in South Second opposite Little Dock street. Cornwallis’ quarters were in Second above Spruce street, and Major Andre lived in Dr. Franklin’s house in a court back from High street.”

[56]Thus it is you can see that our city was literally filled with lobster-backs, and not only the city, but the banks of the river, while in the stream itself lay their ships-of-war, and we three lads were forcing ourselves to believe we could move at will, carrying information to our people at Valley Forge, or wheresoever it might be wanted, without running into these red-coated scoundrels who had come overseas to whip us into loving the king.

I believe now it would have been wiser had we gone boldly up the Delaware beyond Frankford, and there let Master Dingley take his chances of going across country to the Schuylkill; but he had spoken as if the only way for us to proceed would be to pull down the river as far as League island and then up the Schuylkill, therefore, without considering how much more of danger lay in that route than the other, I had consented.

Therefore was our journey more than three times what it should have been had we proceeded, as I now believe, with more of common sense in our methods.

Now, after having set down all dangers which compassed us, as if making ready to tell some tale of wondrous adventure, I am forced to come down from my high horse and say that we sailed, or rather rowed, the boat directly around the city until we were come to the Falls of the Schuylkill, without having been hailed by man or child.

Here it was, as a matter of course, that Master Dingley counted to set off by himself, and when he would have praised us for what we had done in his behalf, I know full well that my cheeks were mantled with shame, for children half our age could have performed the work equally as well under the same circumstances; but yet he put it as if we had accomplished what might have been brought about by none others.

It was a little past midnight when we pulled up under a clump of bushes that he might step ashore, and waited there to hear what he had to say regarding our forming a company of Minute Boys.

Until this moment we had not ventured to speak one with another, save in the most cautious of whispers, and only on such matters as were absolutely necessary for the working of the craft. But now we were in comparative safety, he harked back to his proposition that we band ourselves together in a company for the purpose of doing whatsoever[58] we might to aid the colonies, and took down our names, together with such information as would serve to show him where we lived if peradventure he came into the city, or sent another who would seek us out.

The result of all his talk was, as might be supposed, the agreement on our part to do, without loss of time, exactly as he had proposed.

We even went so far as to say that he might, on any day at the hour of noon, find one of us three lads loitering roundabout the front of the London Coffee-House, agreeing to go there regularly as if it was a post of duty, and to hold ourselves in readiness to perform whatsoever anyone, who could show to our satisfaction that he had come from the American camp, should desire us to do.

“I’m thinking that before a week has passed I shall visit at the home of one or another of you lads, for now that you have agreed to do that which will provide us with means of sending information out from the city, whosoever goes there to spy upon the Britishers may remain, without taking the many chances of detection by going out himself frequently.”

Then Master Dingley had very much more to say regarding our duties, and of what value we might be to the colonies, all of which it is not necessary I should set down here, for if so be I ever bring to an end this poor attempt at a story of the Minute Boys of Philadelphia, you will see, as one incident follows another, that which he had set for us to do.

He lost no time after receiving our promises that we would get together immediately to raise our company of Minute Boys, and also that one or[59] another of us would be in front of the London Coffee-House each day; but then left us, moving away at a swift pace as though minded to finish his journey before sunrise, if indeed that might be possible.

It would have pleased me right well if we could have stayed there within the shelter of the bushes during a certain time, for I was wearied as if having labored severely, when, as a matter of fact, I had worked no harder than I would have worked had we been out on a pleasure voyage. The anxiety, the fear that we might come suddenly upon the lobster-backs, was what had worn me down almost to the verge of exhaustion; yet I knew that we must continue on, for unless our journey was done before daybreak, and our skiff back in her old hiding place, then were we come to grief.

Therefore it was that immediately Master Dingley disappeared amid the bushes, we pulled the Jolly Rover out into the stream, and, having grown careless, I suppose, because of coming thus far in safety without meeting any who might do us an ill turn, instead of taking due heed to remain within the shadow of the bank, we kept the middle of the river, giving little or no heed to the noise which might be made by the oars. As young Chris said, it would be time enough to creep along at a snail’s pace while remaining hidden from view, when we were come to where there was chance of being overhauled by the red-coats.

But however boldly we might go on, our progress was not so rapid but that there were signs in the eastern sky of coming day when we neared Gilson’s point, and even a blind man could have[60] said that we would not be able to gain Dock creek before the sun had fairly shown himself.

All this at the moment did not seem of very great importance. We could readily enough find a hiding place for our skiff during a twelve-hours, and strike across the city to our homes, contenting ourselves with the knowledge that we would return next night to carry the Jolly Rover back to Dock creek.

Therefore it was at the next clump of bushes, or rather thicket, which we came upon, the skiff was run up on the bank, and we spent no little time in hiding her securely amid the foliage, after which we set off at a rapid pace for home, having, as it may well be supposed, an eye out for any straggling lobster-backs.

Strange as it may seem, it was not a Britisher who brought us for the time being to grief, but rather one of our people—I might almost say one of our own comrades.

When the day had fully dawned we were no less than a mile from Chestnut street. Then was the time when it seemed that we might safely come upon any number of Britishers, for surely lads of our age were likely to be out thus early in the morning, for pleasure, if not on some household errand.

We were walking carelessly along, feeling that the matter which we had in hand was well finished, and congratulating ourselves that, lads though we were, we had within the past four and twenty hours saved the life of a man who was struggling to aid in this war against the king.

Suddenly we came upon Benjamin Baker, “Skinny” we called him, a lad for whom I never[61] had any great affection, nor did I consider him an enemy, save in so far as his father was a rabid Tory.

Now if I had had my wits about me, I would have seen by the expression on Skinny’s face that he knew more concerning our movements than we could readily suspect, for there was a certain ugly leer upon his face as he halted us by coming to a full stop directly in our path, as he asked:

“Are you lads out often as early as this?”