THE CAPTAIN AND THE CAPTAIN’S MATE.

By Alfred Terry Bacon.

A few days ago as I was coming out of the dark mouth of a cañon, glad to be once again in the low afternoon sunshine and the free air, there rang out from the blooming plum-thicket beside me a clear, low whistle, repeated often. It was only a curlew hidden down by the brook, under the sweet-scented canopy of flowers; but the whistle came again so sweetly and boyishly that my thoughts flew far away; the tired horse fell into a walk; the reins dropped from my hand over the high Mexican saddle-horn; the mountains and the flower-covered valley seemed blotted out of sight, and instead there came up a vision of a little brown-eyed boy, who lives two thousand miles away—he seemed to be standing before me and looking up, whistling just as the curlew whistles.

But there was no one near. I was alone among the mountains, twenty miles away from any man, and twice as far from any whistling lad. It was only a little vision that the curlew’s note called up for me, but I was grateful to the hidden bird; for that clear remembrance was like sight, and it was long since I had seen a human face or heard a voice. The curlew calling by the brook never knew that it was doing a kindness for a boy far away on the other side of the continent; but in jogging my memory it reminded me of a letter, lying tucked away, which had cost its writer a great deal of hard work—a letter from the brown-eyed lad who thinks the life of a backwoodsman almost as interesting as the life of Robinson Crusoe and the other wonderful men in the story-books. Perhaps there are some other boys who would like to hear how a man lives all alone in the Rocky Mountains.

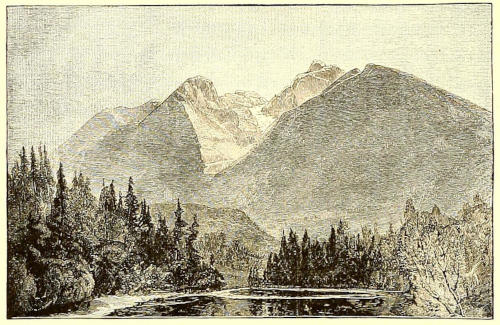

Near the central part of the Territory of Wyoming there is a group of mountains which belong to the Rocky Mountain system, though they are far separated from the highest range. All the mountains are higher than any of our Eastern ranges; but standing in the midst of plains that are many thousand feet above the sea, their general height does not seem great. They are very beautiful in their covering of heavy pine forests with countless tall crags and towers and sharp obelisks of natural rock rising from their summits; and in the center of the group there stands one lofty peak rising far above all its fellows. While all the mountains around were gay with spring flowers, its high head was still wrapped in snow; and now as mid-summer approaches, it is still crowned with a white wreath which will only melt away in the late summer, to return in the early autumn.

The Rocky Mountains are unlike the other great ranges of the world, in having broad, smooth, grassy valleys scattered everywhere among them. Some of these valleys are of very great size, even among the highest mountains, and they are so different from other mountain valleys that they have received a different name; they are generally called parks. This lower group of mountains also, like the great main range, has these lovely natural parks of smaller size. The largest and most beautiful of them all, a mile in width and many miles in length, lies along the eastern side of the great[724] peak; and just where the evening shadow of the mountain falls across the park, shutting off an hour or two of late sunshine, there stands a little lonely log cabin, which is my hermitage. There I am spending a month or two, far away from men, like Robinson Crusoe. I have, to be sure, the company of a horse and a dog, but there is no man—not even a Man Friday; and therefore, as it is not possible for me to talk to any one, I must do a little talking with my pen, and tell what a queer sort of a life I lead. For even in this wilderness I have one great comfort which was denied to poor old Robinson—sometimes, by taking long rides, I can get letters; though, as the post-office is fifty miles away, mail days are very scarce. Still, slowly passed along from ranch to ranch, letters come and go; and so, in time, what I write will reach the railroad and then the outer world.

Life in this part of the globe is not always so lonely. On nearly all the rivers and creeks of Wyoming there are ranches scattered at distances of ten or twenty miles apart. On the eastern edge of these mountains, there is a ranch only eight miles away from my hermitage, and there is another in the foot-hills on the western side, not twenty miles away. But now all the ranches are deserted, for the only business in all this region is the raising of cattle, and through the early summer all hands are hard at work on the “round-ups,” which run over the whole breadth of the territory, searching for cattle scattered by the storms of the last winter. Through the cold and the darkness and the deep snows of winter Crusoe-life would, indeed, be rather too hard to bear. Then, there were three of us together in the little cabin, and there were sometimes friendly visits between the men on the distant ranches. But now, alone in the wilderness, twenty miles from any human being, I feel the loneliness less than did we three together in the still, dead winter; for the whole world is alive and beautiful.

No one knows, moreover, how much pleasure there is in the friendship of an affectionate dog and an intelligent horse, until he is shut off from all other company, and is obliged to make them his intimate friends. Gip and Monkey, my dog and my horse, spend so many hours of every day exploring the mountains with me, that we have grown to be very faithful friends.

A hermit, you know, usually has not much work to do. Those old fellows who used to hide themselves in caves and deserts, in old times, spent most of their days in solemn meditation; but I am not just that kind of[725] a hermit. To sit still and think all the time would be the hardest work in the world for me. The only necessary work that falls to my lot at present is keeping the camp, preparing food and looking after a small band of horses that are running at large in the park. My first task is to ride a few miles up the park and see that the horses are on their proper range; and after that, all the day is free for reading or writing or hunting or wandering about through the mountains, finding fresh varieties of flowers or exploring unknown cañons or climbing the tall crags to look across the mountains to the vast plains that stretch away as far as the eye can reach, like a blue sea. In these daily rides through the wild mountains there is so much that is new and strange to Eastern eyes, so much that is beautiful and grand, so many kinds of curious wild animals, such quantities of gay flowers never seen in the States, that there is enough pleasure in them to make up for all the loneliness of these few weeks.

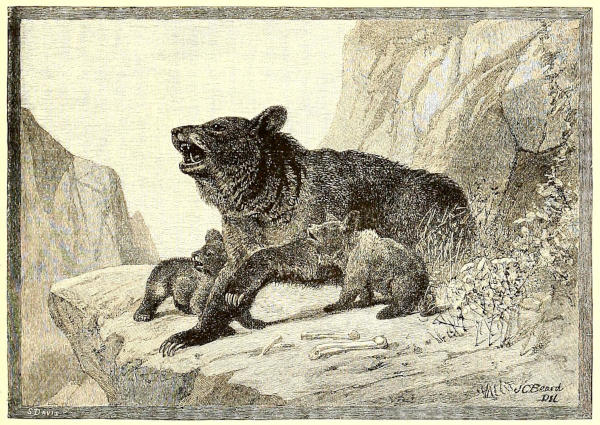

SOME OF THE UNSOCIABLE NEIGHBORS.

We seem to be alone most of the time—Monkey, Gip, and I—and that is why we are such friends; but we are not alone so much as we seem to be. There are plenty of neighbors upon the mountain-sides, and some that wander through the park; but they are so very unsociable that when they see us coming they walk the other way. But then it is true, to be sure, that some of them are not always very kindly treated by us when we meet them, so perhaps we are to blame. There are two families of neighbors, who live in caves on the mountain, for whom I have a great respect. I would not give them offense on any account, for they are very powerful, and usually have things all their own way in the neighborhood. They are the brown bears and the gray bears. Often I see their great fresh foot-prints in the mud along the creeks when I go out in the early morning. The tracks look as if a man with very large, broad feet had been running bare-footed through the mire. I never follow their trail very far to see where they have gone, for I prefer to have a friend or two with me when I go to make the acquaintance of these mighty gentlemen or the members of their families.

At the nearest ranch on the western side of the mountains, there lives a German who was the first pioneer to bring cattle in among these valleys. The encounters that he has had with all the various animals that live in the forest are very interesting. Not long ago, this old fellow built a new cabin for himself at the foot of a mountain. Before his house was finished, he went out one day and killed a fine fat deer. Bringing the carcass home at night, he hung it up against the back of[726] his house, and then hanging a blanket over the doorway which was still without a door, he went to bed. He slept soundly, but there dimly seemed to him to be some disturbance about the house during the night; and when he went out in the morning, every bit of his fine deer was gone, and the bear tracks up and down the mountain-side showed what had become of it. But game was plentiful, and it was not long before his deer was replaced by a big-horned sheep, which is the most tender and juicy meat that ever was eaten. This time he was more careful, and lay awake half the night, fearing that he should lose his stock of fresh meat. When it was very late and he was about to give up watching, he at last heard a sound at the back of the house. Something was at work on his wild mutton. There was a noise of scratching and tearing. It seemed as if several bears were making short work with his meat. He seized his loaded rifle and jumped out of bed with very scanty clothing on. Going to the doorway and drawing aside the blanket, he saw that the night was cloudy and as dark as Egypt. He stopped and thought for a moment that it would be impossible to kill a bear in such darkness, even if he should be able to hit it, for these beasts are so tough that they will carry a dozen bullets about in their bodies without much inconvenience, if they are not wounded in the heart or the brain. So our friend laid down his rifle and took instead a loaded shot-gun. “This is the thing for them,” he said to himself; “it will pepper them all over and scare them so they never will come again.” Then, with gun in hand he silently climbed the projecting logs at the nearest corner of the cabin, and creeping across the roof, peeped over the edge above the place where the sheep was hung. Something appeared to be moving below in the darkness. Taking a random aim, he blazed away. The shot scattered and evidently took effect; for there arose a chorus of growls and howls and yells that would have made the bravest man’s hair stand on end; there was a scampering and shuffling of many feet up and down, and around the cabin; even in the thick darkness he could see many great fat creatures running and sniffing angrily about to find who had attacked them. He saw that he was besieged on his own roof by at least a dozen furious, hungry bears. “They didn’t scare worth a cent,” he said. It was not long before they discovered whence the shot had come, and knowing very well that there is strength in numbers, they determined to have that man for supper, even if they had to put off their supper till breakfast-time. So while some sat down here and there, the others walked about, grunting and growling over their injuries. Bears can climb quite as well as men, and old Frank stood with fear and trembling in the middle of the roof, ready to receive with the butt of his gun the first nose that should rise above the edge. If two had happened to mount the roof on opposite sides, there would have been a small chance of life for the poor man. But the bears thought that solid ground was the safer place for them, so there they staid; and up above sat old Frank shivering, how long he never knew. It seemed centuries. It was a sharp, frosty autumn night, and, as he had on very little clothing, Frank was soon chilled almost to his bones. But the bears’ coats were warm enough. They were more hungry than they were cold, so there they sat and growled and waited for their prey to come down and be eaten. Soon a bitterly cold wind began to blow. Every joint in the poor man’s body stiffened; but it seemed pleasanter to freeze to death than to be eaten up by those ugly beasts, so he bore his discomfort as best he could. The hours of that night seemed to be endless, and the chill grew terrible; but at last a dull gray streak appeared in the East. No man was ever more glad to see the first sign of dawn than was that chilly watcher. Bears are very shy by daylight, and as the twilight little by little grew into broad day, Frank’s visitors trotted away disappointed and sulky up to their dens on the mountain. Their victim, more dead than alive, was able at last to climb down, and kindle a fire to warm himself. He still lives to tell the story in the same log cabin; but it has a good stout door now, and he will never again go bear-hunting with a shot-gun.

So you see it is quite as pleasant not to have the bear families too neighborly. They rarely come out of the woods by daylight, except in late summer and autumn when the plum-thickets are hanging full of fruit; and so, fortunately, we do not often see them.

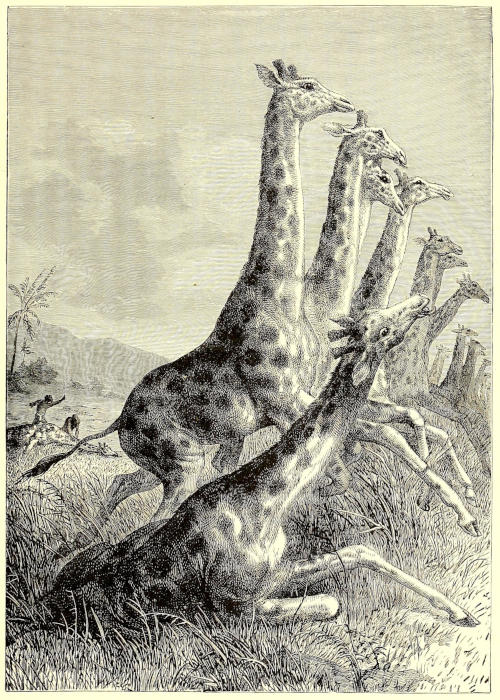

The most sociable of all our wild neighbors is the prong-horned antelope, of which there are several bands running up and down the park. Every day as I ride out to the horse range I meet some of them; often, in suddenly mounting the crest of a ridge, I surprise a little herd grazing just beyond. Then it is beautiful to watch them as they bound gracefully away down the slope with the speed of a bird, seeming hardly to touch their slender limbs to the ground as they fly along. Gip likes nothing better than to go tearing after them as long as his breath holds out; though that small dog always finds it a hopeless chase, for only greyhounds and the swiftest horses can overtake the antelope when it is strong and fat from feeding freely on the fresh June grass.

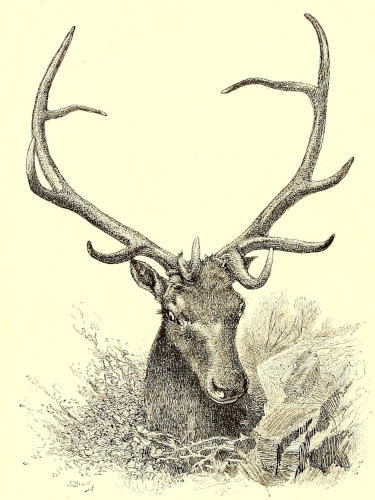

HEAD OF THE PRONG-HORNED ANTELOPE.

Returning a little while ago, after many weeks of civilized life in a Colorado town, I found the[727] old cabin deserted; for those who had been my companions there had gone far out on the plains to look after our wandering cattle. In the late afternoon, when the peak’s shadow fell across the valley, while I was busy making ready the simple supper, Gip stood in the doorway on guard, and I heard him give a long, low growl of suspicion. Looking out, I saw two pretty antelopes standing before the door, not a stone’s throw away, peering about in a timid, curious way to see what change had come over the little house which before had been so quiet. It is not common to see them so very near, and they were so pretty and graceful that I could only stand and admire them for a moment, forgetting my need of fresh meat. Their little hook-shaped horns and dainty hoofs are as black as polished jet; their eyes are very large and soft and dark; their bodies are a bright tawny color, but the throat and breast and limbs are snowy white. There are few animals in the world that[728] are more elegant both in shape and in their movements than the prong-horned antelope. They came tripping down the slope with all the airs and graces of two little dandies; now trotting easily forward; now clearing a fallen tree with a beautiful flying leap; now stopping a moment to gaze and sniff about for possible danger. It was quite flattering to a lonely hermit to receive a visit from neighbors as handsome and stylish as these. But, though a friendly visit would be very pleasant, a full larder would be still pleasanter. Fortunately for my shy visitors, all the arms and ammunition had been stowed away while the house was closed, and could not be procured before the wary creatures had trotted on out of easy rifle range.

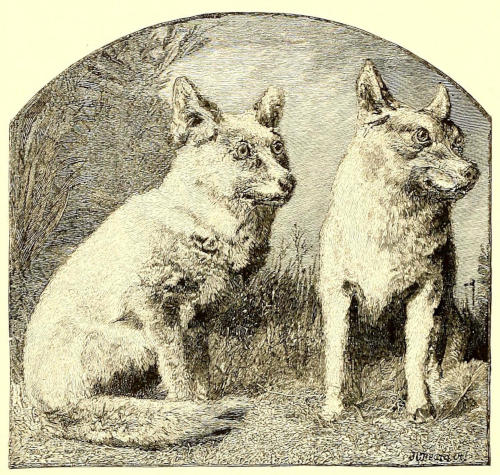

COYOTES, OR PRAIRIE WOLVES.

Once in two weeks comes the principal event of my backwoods life,—a horseback ride of about forty miles to carry letters to the nearest ranch, and to get those that have collected there. After riding a few miles along the valley and through a pass, I come out upon the open rolling country that stretches away for hundreds of miles without any covering of trees or bushes except along the streams; for this western prairie land is so dry that only grass and cactus and low herbs can grow upon it. The rolling land is green, and spangled with flowers through May and June; but after mid-summer it becomes as dry as a desert, and in that way kind Providence changes the standing grass into hay which will feed the thousands of cattle and horses and wild creatures through the winter.

PRAIRIE DOGS.

As I ride out of the pass on these regular journeys for the mail, a coyote, or prairie wolf, that lives close by among the rocks, often comes rushing out with a doleful howl, and acts as if wishing to make acquaintance with Gip. Both the wolf and Gip seem to understand that they are blood relations. They are nearly of equal size, and they run up to each other as if they would like to be friends; but when they are close together, the courage of one or the other always fails. Either Gip turns tail, allowing the wolf to chase him within a dozen steps of the horse’s heels,—or the wolf takes alarm, and Gip runs madly after it until it disappears over a ridge. So the wild dog and the tame one make little progress in their friendship. Yet it is not a very uncommon thing in the Far West even for gentle and intelligent dogs to form a friendship with a pack of wolves, and to go off and live with them, returning now and then to pay short visits to their old masters. But more often if a dog falls in with a pack of wolves, he is quickly torn in pieces by them.

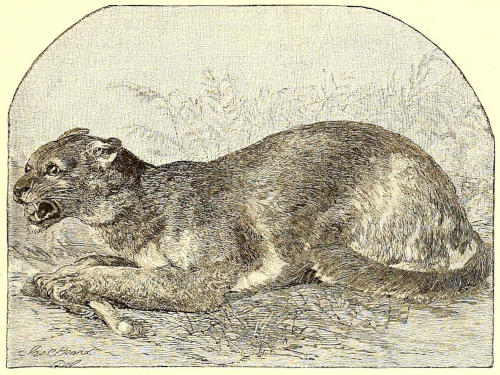

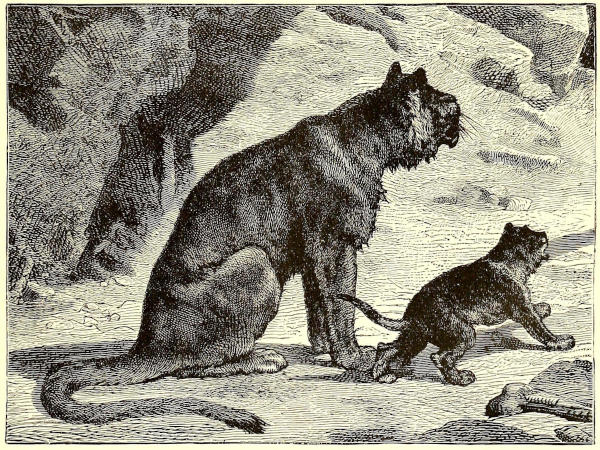

THE MOUNTAIN LION.

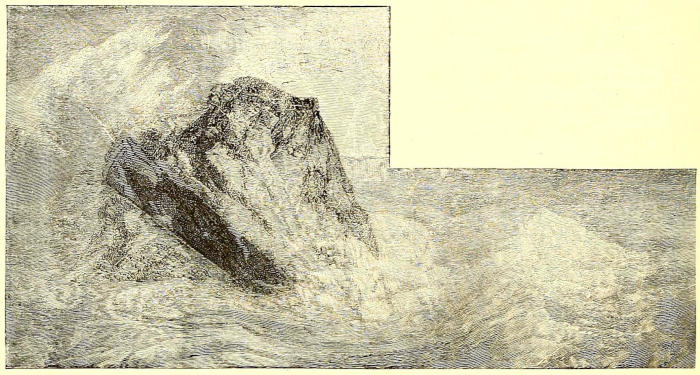

THE HOME OF THE BIG CAT.

Early in the morning, before the peak has begun to gather its cap of thunder clouds which break in showers every afternoon, and while the air through the whole valley is cool and very sweet with the perfume of a million flowers, I start out for my daily ride. First there is a mile over the rich grassland along the creek where the gay flowers grow in far greater variety and beauty than in any Eastern fields; then there is a long stretch of dry, rolling land which is all one great city of prairie-dogs. At the approach of strangers there is great excitement through this town of little yellow pigmies. Those which are looking out from the highest point give a few warning calls. Then there is a tremendous scattering and scampering in all directions of the fat, short-legged[730] little bodies in so hot haste that they look like balls of yellow fur rolling across the gravel. Some have been out feeding, and more have been about gossiping with their neighbors and making morning calls, for they are famous little busybodies: but when they hear the warning, all fly at full speed to their own homes. Then when every one is sitting at the mouth of its hole, they are ready to defy the world. For a man and a horse they care little, but at the sight of a dog, the city is in an uproar; and, feeling perfectly safe by their own homes, they delight to tease him. There is such a Babel of shrill little voices chattering, scolding, squealing, and yelping from hundreds of gravel-heaps, that Gip stands for a minute perplexed, not knowing on which one to spring first; then like a flash he darts away to the nearest hole where a jolly little tormentor is chattering its defiance. The prairie-dog stands still in the doorway of its house, scolding and twitching its tail as its enemy comes charging down, until Gip’s nose seems almost upon it; then as quick as a wink, the little tail flies up and Mr. Prairie-Dog is far away into the earth by the time Gip has fairly reached the door of his house. Then every dog in the town redoubles its chattering, and it seems as if a ripple of low laughter ran through the company at the disappointment of their enemy. But Gip, after ramming his head as far as it can be forced into the burrow, draws it out with a sniff of regret and then is off again, full tilt, after the next little saucy rascal that sits on a neighboring sandheap, making merry over his perplexity. Again he almost has one; the prairie-dog sits unmoved until Gip comes within a yard of the hole, and then it vanishes. It seems a very narrow escape for it; but it is always just so narrow, and yet they always escape. As long as man and dog are in sight they keep up their shrill din, like the chattering of a thousand monkeys; and as long as we are in their village, Gip flies madly from hole to hole, always just so eager and hopeful, though he has been chasing them all his life and has never yet caught one.

HEAD OF THE WAPITI.

The town of the prairie-dogs is in a beautiful situation. It lies in the broadest part of the park, surrounded by the highest and grandest of the mountains. A few days ago, as I was riding through it in the early morning, I saw an animal some distance ahead running hard toward the woods. Thinking it was a wolf or coyote, I paid little attention at first, but looking closer, I saw plainly that I was mistaken, for its legs were short, and its body long and heavy. It went springing over the grass with long bounds, and its coat of fur was grayish, shading to yellow brown; and I knew it must be one of the great panthers which are generally called mountain lions. I had never before met one, though their great, round footprints, as large as tea-plates, had often been seen in the soft snow the last winter. Like other cats, they like to sleep in the day and to prowl at night. Gip took a long, wistful look at the lion; but he is a small dog, and a very wise one, and he knew his life would be short if he should approach very near to that great creature, so he went back to his hard work with the prairie-dogs, and left me to go galloping off alone for a nearer view of the[731] lion. But Monkey dislikes wild beasts quite as much as Gip, and would never willingly have carried me very near to a beast of prey, even if the lion had not run up into the rocks on the mountain-side before I had seen it very clearly.

Beside the rough confusion of rocks into which the panther ran, there was a gentle grassy slope which seemed to extend to the top of the mountain.

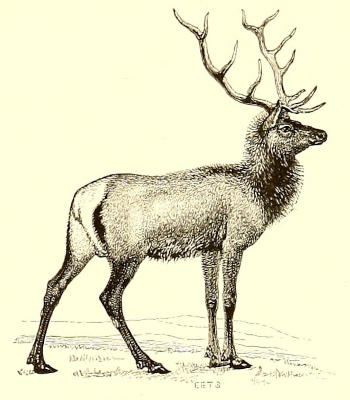

I wanted to have one more look at the big cat, so Monkey had to climb the long ascent, much against his will, keeping as near to the rocks as possible; and very soon Gip plucked up courage to follow; but that was the last we ever saw of the mountain lion. However, in wandering up near the top of the mountain, I came on tracks that were quite as interesting to me as was the lion. They were the marks of a cloven hoof, nearly as large as the tracks of an ox, but longer and more pointed. As there were no cattle so high on the mountain, it was plain, at a glance, that they were footprints of the great wapiti, which, in the West, is always called an elk. Hurrying on in hope of catching sight of this great king of the forest, the footprints grew fresher, and soon I came to a glade where the grass, crushed down in spots, showed that a startled band of elk had just risen from their rest, and run away; and so, like a will-o’-the-wisp, they led me on through the forest, always letting me know that they were near, by their fresh tracks, but never quite near enough to be seen. The elk and the big-horned sheep are the shyest of all these wild animals; and the elk have the senses of sight and smell and hearing so very keen, that they will see a hunter, and will run from him, a dozen times for every time that he gets a first sight of them. Their great branching antlers, so large and heavy that a small boy could hardly lift them from the ground, lie scattered everywhere through the grass in the park, for they shed them every spring; and everywhere on the mountain-sides we find their footprints; and yet it is quite a rare event to meet them, and still more uncommon to kill them.

THE AMERICAN ELK.

So all day long, with my pony and my dog, I wandered contentedly along the mountain-side, resting often under cool over-arching rocks or beside the snow-fed brooks, the banks of which are streaked with the crimson of the wild cyclamen; and all day long we tried to pay visits to our shy neighbors; but wherever we called, they were not at home. And, when the late afternoon began to drop blue, gauzy veils of shadows over the east-ward slope of the opposite mountain, we turned back toward the lonely, silent home, which now never hears the sweet sound of human speech.

I can not now tell you of all the queer inhabitants of these mountains; but next time I shall have something to say to you about the beaver, the wild sheep, the buffalo, and some other interesting neighbors of mine.

By William H. Hayne.

[1] “Hussif” (a contracted form of the word “house-wife”)was formerly used as a name for a little bag or case for holding sewing materials.

By Mary E. Wilkins.

When Mr. Hobbs’s young friend left him to go to Dorincourt Castle and become Lord Fauntleroy, and the grocery-man had time to realize that the Atlantic Ocean lay between himself and the small companion who had spent so many agreeable hours in his society, he really began to feel very lonely indeed. The fact was, Mr. Hobbs was not a clever man nor even a bright one; he was, indeed, rather a slow and heavy person, and he had never made many acquaintances. He was not mentally energetic enough to know how to amuse himself, and in truth he never did anything of an entertaining nature but read the newspapers and add up his accounts. It was not very easy for him to add up his accounts, and sometimes it took him a long time to bring them out right; and in the old days, little Lord Fauntleroy, who had learned how to add up quite nicely with his fingers and a slate and pencil, had sometimes even gone to the length of trying to help him; and, then too, he had been so good a listener and had taken such an interest in what the newspaper said, and he and Mr. Hobbs had held such long conversations about the Revolution and the British and the elections and the Republican party, that it was no wonder his going left a blank in the grocery store. At first it seemed to Mr. Hobbs that Cedric was not really far away, and would come back again; that some day he would look up from his paper and see the lad standing in the doorway, in his white suit and red stockings, and with his straw hat on the back of his head, and would hear him say in his cheerful little voice: “Hello, Mr. Hobbs! This is a hot day—isn’t it?” But as the days passed on and this did not happen, Mr. Hobbs felt very dull and uneasy. He did not even enjoy his newspaper as much as he used to. He would put the paper down on his knee after reading it, and sit and stare at the high stool for a long time. There were some marks on the long legs which made him feel quite dejected and melancholy. They were marks made by the heels of the next Earl of Dorincourt, when he kicked and talked at the same time. It seems that even youthful earls kick the legs of things they sit on;—noble blood and lofty lineage do not prevent it. After looking at those marks, Mr. Hobbs would take out his gold watch and open it and stare at the inscription: “From his oldest friend, Lord Fauntleroy, to Mr. Hobbs. When this you see, remember me.” And after staring at it awhile, he would shut it up with a loud snap, and sigh and get up and go and stand in the doorway—between the box of potatoes and the barrel of apples—and look up the street. At night, when the store was closed, he would light his pipe and walk slowly along the pavement until he reached the house where Cedric had lived, on which there was a sign that read, “This House to Let”; and he would stop near it and look up and shake his head, and puff at his pipe very hard, and after a while walk mournfully back again.

This went on for two or three weeks before any new idea came to him. Being slow and ponderous, it always took him a long time to reach a new idea. As a rule he did not like new ideas, but preferred old ones. After two or three weeks, however, during which, instead of getting better, matters really grew worse, a novel plan slowly and deliberately dawned upon him. He would go to see Dick. He smoked a great many pipes before he arrived at the conclusion, but finally he did arrive at it. He would go to see Dick. He knew all about Dick. Cedric had told him, and his idea was that perhaps Dick might be some comfort to him in the way of talking things over.

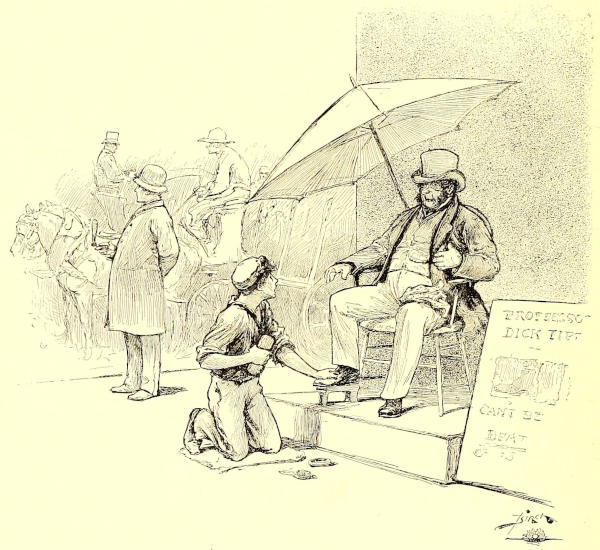

So one day when Dick was very hard at work blacking a customer’s boots, a short, stout man with a heavy face and a bald head, stopped on the pavement and stared for two or three minutes at the bootblack’s sign, which read:

“Professor Dick Tipton

Can’t be beat.”

He stared at it so long that Dick began to take a lively interest in him, and when he had put the finishing touch to his customer’s boots, he said:

“Want a shine, sir?”

The stout man came forward deliberately and put his foot on the rest.

“Yes,” he said.

Then when Dick fell to work, the stout man looked from Dick to the sign and from the sign to Dick.

“Where did you get that?” he asked.

“From a friend o’ mine,” said Dick,—“a little feller. He guv’ me the whole outfit. He was the best little feller ye ever saw. He’s in England now. Gone to be one o’ those lords.”

“Lord—Lord—”asked Mr. Hobbs, with ponderous slowness, “Lord Fauntleroy—Goin’ to be Earl of Dorincourt?”

Dick almost dropped his brush.

“Why, boss!”he exclaimed, “d’ye know him yerself?”

“I’ve known him.” answered Mr. Hobbs, wiping his warm forehead, “ever since he was born. We were lifetime acquaintances—that’s what we were.”

It really made him feel quite agitated to speak of it. He pulled the splendid gold watch out of his pocket and opened it, and showed the inside of the case to Dick.

“‘When this you see, remember me,’” he read.

“That was his parting keepsake to me. ‘I don’t want you to forget me’—those were his words—I’d ha’ remembered him,” he went on, shaking his head, “if he hadn’t given me a thing, an’ I hadn’t seen hide nor hair on him again. He was a companion as any man would remember.”

“He was the nicest little feller I ever see,” said Dick. “An’ as to sand—I never ha’ seen so much sand to a little feller. I thought a heap o’ him, I did,—an’ we was friends, too—we was sort o’ chums from the fust, that little young un an’ me. I grabbed his ball from under a stage fur him, an’ he never forgot it; an’ he’d come down here, he would, with his mother or his nuss an’ he’d holler: ‘Hello, Dick!’ at me, as friendly as if he was six feet high, when he warn’t knee high to a grasshopper, and was dressed in gal’s clo’es. He was a gay little chap, and when you was down on your luck, it did you good to talk to him.”

“That’s so,” said Mr. Hobbs. “It was a pity to make an earl out of him. He would have shone in the grocery business—or dry goods either; he would have shone!” And he shook his head with deeper regret than ever.

It proved that they had so much to say to each other that it was not possible to say it all at one time, and so it was agreed that the next night Dick should make a visit to the store and keep Mr. Hobbs company. The plan pleased Dick well enough. He had been a street waif nearly all his life, but he had never been a bad boy, and he had always had a private yearning for a more respectable kind of existence. Since he had been in business for himself, he had made enough money to enable him to sleep under a roof instead of out in the streets, and he had begun to hope he might reach even a higher plane, in time. So, to be invited to call on a stout, respectable man who owned a corner store, and even had a horse and wagon, seemed to him quite an event.

“Do you know anything about earls and castles?” Mr. Hobbs inquired. “I’d like to know more of the particklars.”

“There’s a story about some on ’em in the Penny Story Gazette,” said Dick. “It’s called the ‘Crime of a Coronet; or, the Revenge of the Countess May.’ It’s a boss thing, too. Some of us boys’re takin’ it to read.”

“Bring it up when you come,” said Mr. Hobbs, “an’ I’ll pay for it. Bring all you can find that have any earls in ’em. If there aren’t earls, markises ’ll do, or dooks—though he never made mention of any dooks or markises. We did go over coronets a little, but I never happened to see any. I guess they don’t keep ’em ’round here.”

“Tiffany’d have ’em if anybody did,” said Dick, “but I don’t know as I’d know one if I saw it.”

Mr. Hobbs did not explain that he would not have known one if he saw it. He merely shook his head ponderously.

“I s’pose there is very little call for ’em,” he said, and that ended the matter.

This was the beginning of quite a substantial friendship. When Dick went up to the store, Mr. Hobbs received him with great hospitality. He gave him a chair tilted against the door, near a barrel of apples, and after his young visitor was seated, he made a jerk at them with the hand in which he held his pipe, saying:

“Help yerself.”

Then he looked at the story papers, and after that they read, and discussed the British aristocracy; and Mr. Hobbs smoked his pipe very hard and shook his head a great deal. He shook it most when he pointed out the high stool with the marks on its legs.

“There’s his very kicks,” he said impressively; “his very kicks. I sit and look at ’em by the hour. This is a world of ups an’ it’s a world of downs. Why, he’d set there, an’ eat crackers out of a box, an’ apples out of a barrel, an’ pitch his cores into the street; an’ now he’s a lord a-livin’ in a castle. Those are a lord’s kicks; they’ll be an earl’s kicks some day. Sometimes I says to myself, says I, ‘Well, I’ll be jiggered!’”

He seemed to derive a great deal of comfort from his reflections and Dick’s visit. Before Dick went home, they had a supper in the small backroom; they had crackers and cheese and sardines, and other canned things out of the store, and Mr. Hobbs solemnly opened two bottles of ginger ale, and pouring out two glasses, proposed a toast.

“Here’s to him!” he said, lifting his glass, “an’ may he teach ’em a lesson—earls an’ markises an’ dooks an’ all!”

After that night, the two saw each other often, and Mr. Hobbs was much more comfortable and less desolate. They read the Penny Story Gazette, and many other interesting things, and gained a knowledge of the habits of the nobility and gentry[736] which would have surprised those despised classes if they had realized it. One day Mr. Hobbs made a pilgrimage to a book store down town, for the express purpose of adding to their library. He went to a clerk and leaned over the counter to speak to him.

“I want,” he said, “a book about earls.”

“What!” exclaimed the clerk.

“A book,” repeated the grocery-man, “about earls.”

“I’m afraid,” said the clerk, looking rather queer, “that we haven’t what you want.”

“Haven’t?” said Mr. Hobbs, anxiously. “Well, say markises then—or dooks.”

“I know of no such book,” answered the clerk.

Mr. Hobbs was much disturbed. He looked down on the floor,—then he looked up.

“None about female earls?” he inquired.

“I’m afraid not,” said the clerk, with a smile.

“Well,” exclaimed Mr. Hobbs, “I’ll be jiggered!”

He was just going out of the store, when the clerk called him back and asked him if a story in which the nobility were chief characters would do. Mr. Hobbs said it would—if he could not get an entire volume devoted to earls. So the clerk sold him a book called “The Tower of London,” written by Mr. Harrison Ainsworth, and he carried it home.

When Dick came they began to read it. It was a very wonderful and exciting book, and the scene was laid in the reign of the famous English queen who is called by some people Bloody Mary. And as Mr. Hobbs heard of Queen Mary’s deeds and the habit she had of chopping people’s heads off, putting them to the torture, and burning them alive, he became very much excited. He took his pipe out of his mouth and stared at Dick, and at last he was obliged to mop the perspiration from his brow with his red pocket handkerchief.

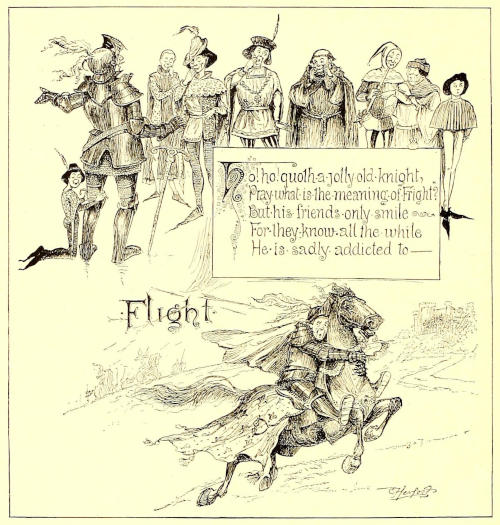

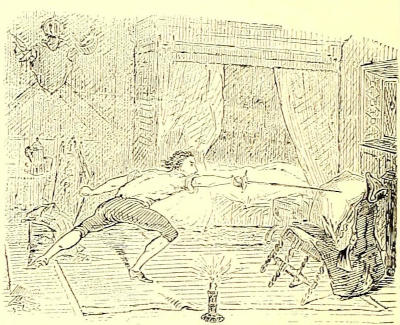

“WHY, BOSS!” EXCLAIMED DICK, “DO YOU KNOW HIM YOURSELF?”

“Why, he aint safe!” he said. “He aint safe! If the women folks can sit up on their thrones an’ give the word for things like that to be done, who’s to know what’s happening to him this very minute? He’s no more safe than nothing? Just let a woman like that get mad, an’ no one’s safe!”

“Well,” said Dick, though he looked rather anxious himself; “ye see this ’ere un isn’t the one that’s bossin’ things now. I know her name’s[737] Victohry, an’ this un here in the book,—her name’s Mary.”

“So it is,” said Mr. Hobbs, still mopping his forehead; “so it is. An’ the newspapers are not sayin’ anything about any racks, thumbscrews, or stake-burnin’s,—but still it doesn’t seem as if ’twas safe for him over there with those queer folks. Why, they tell me they don’t keep the Fourth o’ July!”

He was privately uneasy for several days; and it was not until he received Fauntleroy’s letter and had read it several times, both to himself and to Dick, and had also read the letter Dick got about the same time, that he became composed again.

But they both found great pleasure in their letters. They read and re-read them, and talked them over and enjoyed every word of them. And they spent days over the answers they sent, and read them over almost as often as the letters they had received.

It was rather a labor for Dick to write his. All his knowledge of reading and writing he had gained during a few months when he had lived with his elder brother, and had gone to a night-school; but, being a sharp boy, he had made the most of that brief education, and had spelled out things in newspapers since then, and practiced writing with bits of chalk on pavements or walls or fences. He told Mr. Hobbs all about his life and about his elder brother, who had been rather good to him after their mother died, when Dick was quite a little fellow. Their father had died some time before. The brother’s name was Ben, and he had taken care of Dick as well as he could, until the boy was old enough to sell newspapers and run errands. They had lived together, and as he grew older Ben had managed to get along until he had quite a decent place in a store.

“And then,” exclaimed Dick with disgust, “blest if he didn’t go an’ marry a gal! Just went and got spoony, an’ hadn’t any more sense left! Married her, an’ set up housekeepin’ in two back rooms. An’ a hefty un she was,—a regular tiger-cat. She’d tear things to pieces when she got mad,—and she was mad all the time. Had a baby just like her,—yell day ’n’ night! An’ if I didn’t have to ’tend it! an’ when it screamed, she’d fire things at me. She fired a plate at me one day, an’ hit the baby—cut its chin. Doctor said he’d carry the mark till he died. A nice mother she was! Crackey! but didn’t we have a time—Ben ’n’ mehself ’n’ the young un. She was mad at Ben because he didn’t make money faster; ’n’ at last he went out West with a man to set up a cattle ranch. An’ he hadn’t been gone a week ’fore, one night, I got home from sellin’ my papers, ’n’ the rooms wus locked up ’n’ empty, ’n’ the woman o’ the house, she told me Minna’d gone—shown a clean pair o’ heels. Some un else said she’d gone across the water to be nuss to a lady as had a little baby, too. Never heard a word of her since—nuther has Ben. If I’d ha’ bin him, I wouldn’t ha’ fretted a bit—’n’ I guess he didn’t. But he thought a heap o’ her at the start. Tell you, he was spoons on her. She was a daisy-lookin’ gal, too, when she was dressed up, ’n’ not mad. She’d big black eyes ’n’ black hair down to her knees; she’d make it into a rope as big as your arm, and twist it ’round ’n’ ’round her head; ’n’ I tell you her eyes’d snap! Folks used to say she was part Itali-un—said her mother or father’d come from there, ’n’ it made her queer. I tell ye, she was one of ’em—she was!”

He often told Mr. Hobbs stories of her and of his brother Ben, who, since his going out West, had written once or twice to Dick. Ben’s luck had not been good, and he had wandered from place to place; but at last he had settled on a ranch in California, where he was at work at the time when Dick became acquainted with Mr. Hobbs.

“That gal,” said Dick one day, “she took all the grit out o’ him. I couldn’t help feelin’ sorry for him sometimes.”

They were sitting in the store door-way together, and Mr. Hobbs was filling his pipe.

“He oughtn’t to ’ve married,” he said solemnly, as he rose to get a match. “Women—I never could see any use in ’em, myself.”

As he took the match from its box, he stopped and looked down on the counter.

“Why!” he said, “if here isn’t a letter! I didn’t see it before. The postman must have laid it down when I wasn’t noticin’, or the newspaper slipped over it.”

He picked it up and looked at it carefully.

“It’s from him!” he exclaimed. “That’s the very one it’s from!”

He forgot his pipe altogether. He went back to his chair quite excited and took his pocket-knife and opened the envelope.

“I wonder what news there is this time,” he said.

And then he unfolded the letter and read as follows:

“Dorincourt Castle

“My dear Mr Hobbs

“i write this in a great hury becaus i have something curous to tell you i know you will be very mutch suprised my dear frend when i tel you. It is all a mistake and i am not a lord and i shall not have to be an earl there is a lady whitch was marid to my uncle bevis who is dead and she has a little boy and he is lord fauntleroy becaus that is the way it is in England the earls eldest sons little boy is the earl if every body else is dead i mean if his farther and grandfarther are dead my grandfarther is not dead but my uncle bevis is and so his boy is lord Fauntleroy and I am not becaus my papa was the[738] youngest son and my name is Cedric Errol like it was when I was in New York and all the things will belong to the other boy i thought at first i should have to give him my pony and cart but my grandfarther says i need not my grandfarther is very sorry and i think he does not like the lady but preaps he thinks dearest and i are sorry becaus i shall not be an earl i would like to be an earl now better than i thout i would at first becaus this is a beautifle castle and i like every body so and when you are rich you can do so many things i am not rich now becaus when your papa is only the youngest son he is not very rich i am going to learn to work so that I can take care of dearest i have been asking Wilkins about grooming horses preaps i might be a groom or a coachman, the lady brought her little boy to the castle and my grandfarther and Mr. Havisham talked to her i think she was angry she talked loud and my grandfarther was angry too i never saw him angry before i wish it did not make them all mad i thort i would tell you and Dick right away becaus you would be intrusted so no more at present with love from

“your old frend

“Cedric Errol (Not lord Fauntleroy).”

Mr. Hobbs fell back in his chair, the letter dropped on his knee, his penknife slipped to the floor, and so did the envelope.

“Well!” he ejaculated, “I am jiggered!”

He was so dumbfounded that he actually changed his exclamation. It had always been his habit to say, “I will be jiggered,” but this time he said, “I am jiggered.” Perhaps he really was jiggered. There is no knowing.

“Well,” said Dick, “the whole thing’s bust up, hasn’t it?”

“Bust!” said Mr. Hobbs. “It’s my opinion it’s all a put-up job o’ the British ’ristycrats to rob him of his rights because he’s an American. They’ve had a spite agin us ever since the Revolution, an’ they’re takin’ it out on him. I told you he wasn’t safe, an’ see what’s happened! Like as not, the whole gover’ment’s got together to rob him of his lawful ownin’s.”

He was very much agitated. He had not approved of the change in his young friend’s circumstances at first, but lately he had become more reconciled to it, and after the receipt of Cedric’s letter he had perhaps even felt some secret pride in his young friend’s magnificence. He might not have a good opinion of earls, but he knew that even in America money was considered rather an agreeable thing, and if all the wealth and grandeur were to go with the title, it must be rather hard to lose it.

“They’re trying to rob him!” he said, “that’s what they’re doing, and folks that have money ought to look after him.”

And he kept Dick with him until quite a late hour to talk it over, and when that young man left, he went with him to the corner of the street; and on his way back he stopped opposite the empty house for some time, staring at the “To Let,” and smoking his pipe, in much disturbance of mind.

(To be continued.)

WAITING FOR A COLD WAVE.

When the Hudson River was first seen by St. Nicholas, or rather by his image, which was the figure-head of the Dutch ship Goode Vrouw, there were more salmon in the water than there were wild grapes about the Indian wigwams which stood where New York City stands to-day. That was a few years after the rediscovery of the river by Henry Hudson in 1609.[2] But, in course of time, the salmon went the way of the Indians. The last native Hudson River salmon was caught in a net in New York bay about 1844; but, more recently, attempts have been made artificially to stock that river and others with this fish, and within two years a few have been caught, the only salmon taken from the Hudson in forty years.[3] When St. Nicholas made his first visit to our shores, there were salmon in every river along the Atlantic coast, north of the Delaware. But, as fishermen became numerous, as dams were built across the rivers, and as the water was made impure by town and city drainage, the salmon were driven northward, just as the Indians were driven westward. The salmon were forced to leave the Connecticut—another river into which there has been hope of introducing them again; they left the Merrimac when it was given over to manufactories; and now few salmon are to be found south of the rivers of eastern Maine. Beyond, they visit the rivers of the British Provinces, Labrador, the Hudson Bay country, and even Greenland,—for one variety of salmon is a fearless Arctic explorer, and penetrates the Arctic Circle. The salmon is as much at home in Iceland and Norway as in England, Scotland, and Ireland. On the north-western American coast, from northern California, Oregon, and Washington, to Alaska and beyond, there have always been vast numbers of this wonderful fish.

I say wonderful, because the salmon is the king of all game fishes, and because he goes under so many names, and has habits so curious that he has puzzled naturalists for hundreds of years. And his pink flesh is so prized that the salmon fisheries on this continent alone yield millions of dollars every year.

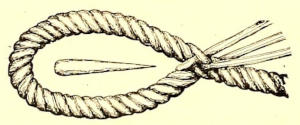

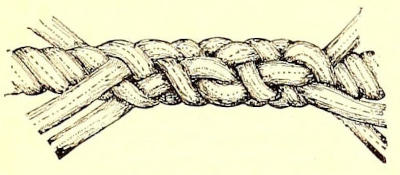

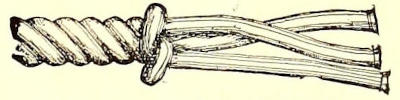

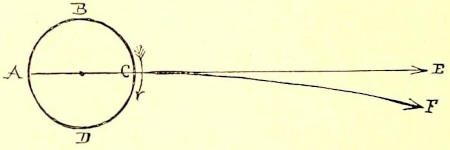

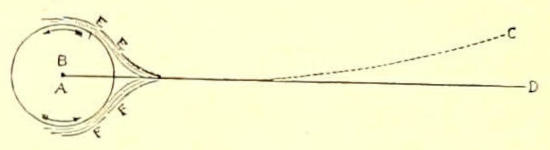

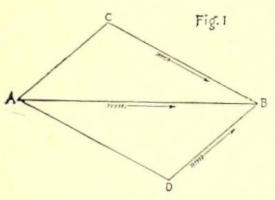

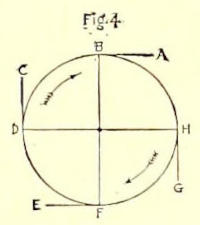

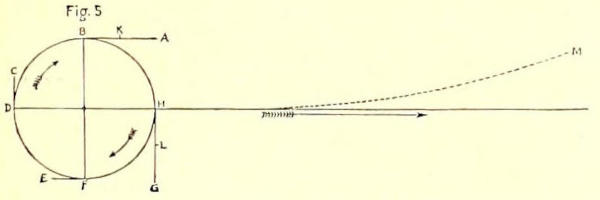

The gamy qualities of the salmon, which cause the fly-fisherman to rate him above all other fishes, are his enduring strength and his great activity. The salmon and the blue-fish are the strongest game fishes known, and the former reaches a far larger size than the latter. According to one writer, “the salmon and the sword-fish are the fastest swimmers of all the forked-tail fishes.” Only a fast running-horse could outstrip a salmon; for it is estimated that the salmon swims a mile in less than two minutes. But the horse would be left behind in a long race, for the fish can cover thirty miles in an hour. When leisurely ascending rivers, with frequent rests in[740] attractive pools, the salmon averages from fifteen to twenty-five miles a day. In leaping, the salmon can easily beat the horse, for salmon have leaped up waterfalls twelve feet high. It was formerly supposed that the salmon, when about to jump, bent himself double, and took his tail in his mouth, so that he was like an elastic bow drawn tight. Then it was thought that he suddenly let go, his tail striking the water with great force, and away he went through the air. But now we know that the salmon prepares for a leap just as a boy does, with a short, sharp run. If the water at the foot of the dam or fall is not deep enough to allow this preparatory run, the salmon can not jump. If there is water enough, he starts from the bottom, his powerful tail working as rapidly as the propeller-screw of a steamship. Aided by the pectoral fins, the upward movement grows quicker and quicker, until with a last muscular effort the salmon shoots from the water, his tail still vibrating for an instant, then becoming motionless, as the fish curves through the air and comes down above the obstacle. If a dam be built so high as to be impassable, the salmon will leave the river altogether, for instinct always leads them to the head-waters, where they lay their eggs. So fish-ladders and fish-ways of various kinds have been invented to help salmon and other fishes to surmount natural or artificial barriers. Fish-ladders have been constructed by the aid of which salmon ascend falls over thirty feet high. As soon as salmon enter rivers on their way from the sea they begin to jump, like a crowd of boys just let out of school. Standing on the shore of a salmon river in June or July, you will every now and then see the fish leap four or five feet out of water, glistening like polished silver, then curving over and falling with a heavy splash. Or sometimes their back fins will roll lazily out of the water, and you will be reminded of a school of porpoises. But there is nothing lazy about the salmon when once he is hooked. If there is a twenty-five pound salmon at the end of your line, jumping nearly as high as your head in his struggles to rid himself of the hook, you will be sure to think of nothing except that fish.

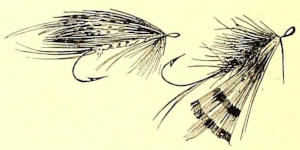

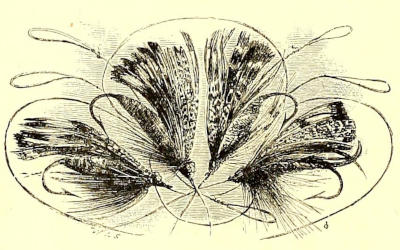

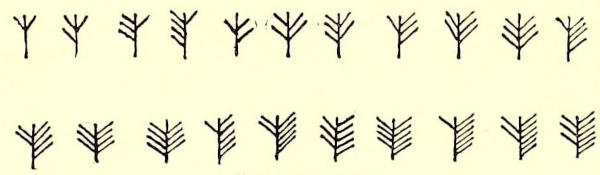

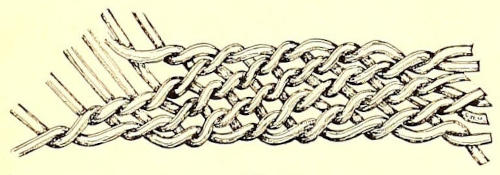

SALMON FLIES.

But before the salmon reaches a weight of twenty-five pounds, he appears in so many and so different forms that very wise men have been unable to recognize him. When the salmon is just hatched, he is known as fry, or fingerling. Then he becomes a parr, or samlet, also called pink, or brandling, on some foreign rivers. The parr changes to a smolt, the smolt to a grilse, and the grilse finally develops into the salmon. The latter, when running fresh from the sea, are called white salmon, and when they are descending rivers after spawning, they are termed kelts, or black salmon. Other names given to salmon after spawning-time are kippers and baggits, or shedders. So the salmon, like the royal fish that he is, has as many names as a prince of one of the royal families of Europe. The alevin, or baby salmon, is hatched in from thirty to one hundred days after the eggs are laid in furrows in gravelly beds which are scooped out by the parent fish, near the head-waters of cold, clear rivers. Presently the alevin grows into the fry, or pink, which is an absurd little fish about an inch long, goggle-eyed, and with dark bars on its sides. When some three months old, the fry makes a change like that of a chrysalis into a butterfly. It becomes a shapely little fish with a forked tail, and brilliant carmine spots shine out on its sides. Its back is of a dark slaty color, and the bars are less strongly marked as the parr grows older. The greediest of trout is not more hungry and active. I have often seen a dozen tiny parr jump from the water at my flies. Once, when coming down the Restigouche in a canoe, with our rods laid aside, and the flies dangling just over the water, two parr leaped together and hooked themselves, although they were hardly four inches long. These pretty little fishes, which[741] one might readily mistake for trout, were once supposed to belong to a species entirely distinct from the salmon. Naturalists were also puzzled by finding that some parr remain for nearly three years in fresh water. So they concluded that these latter parr never went to sea at all, and considered them a species by themselves, which they called Salmo samulus. But nature was finally seen to be wiser than the naturalists. Nature has decreed that only half the parr hatched in a given winter shall go down to the sea at one time, and in this way protects the race from the chance of wholesale destruction. So we are now told that some of the parr develop more rapidly than others, and migrate to the sea in their second spring, while others remain in the river a year longer, and some for still another year.

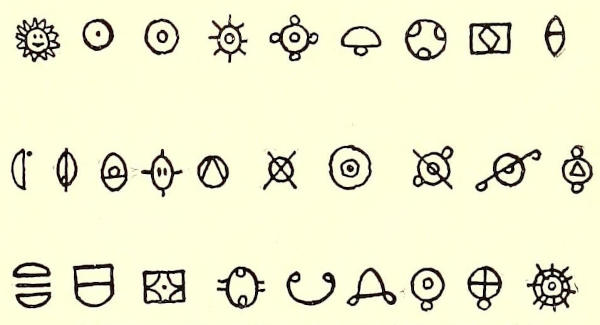

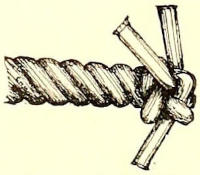

A FISH-LADDER AROUND A DAM.

When the time for this migration approaches, the parr, which has been steadily growing plumper, undergoes another curious change. The carmine spots fade out, and the soft skin becomes covered with silvery scales which obscure the dark bars on the sides, although the scales can easily be rubbed away. At this period the young salmon is called a smolt, and the smolt was also a riddle to wise men, for a long time. It was thought that smolts which went down to the sea weighing three or four ounces, returned to the rivers in three months weighing six or eight pounds. Of course, such a gain as this was a very wonderful, indeed an unequaled performance, like the “swellin’ wisibly” of the Fat Boy in the “Pickwick Papers.” It is now believed, however, that the smolt requires a year or fifteen months at sea for this great gain in weight. Then he returns to his native river, no longer an insignificant smolt, but a vigorous, beautiful grilse. The grilse is more slender than the salmon, the tail more forked, the scales more easily removed, and the top of the head and of the fins is not quite so black. But the grilse’s sheeny, satiny sides are even more brilliant than the salmon’s, and it is more playful and active, although its strength is less enduring. After the grilse has frolicked its way to the head of the river and spawned, it returns to the sea. When it visits the river again, the next year, it has become a full-grown salmon. These are the successive stages of the salmon’s life.

But, even in the last and most familiar stage, the salmon’s habits are not fully understood. It is known that both young and old salmon, after descending a river, remain for a time in the brackish water at the river’s mouth, where they get rid of fresh-water parasites which have become attached to their sides, and where their scales are hardened by a diet of small fish; but where in the sea salmon go, no one knows. After leaving the coast, they disappear. They have been found in very deep water hundreds of miles from any salmon river; but their marine feeding-grounds are still undiscovered. In the spring they suddenly re-appear at the mouths of rivers, where they linger to free themselves from marine parasites. While in salt water, they will never jump at a fly; but as soon as they enter the fresh water of the Canadian rivers, in June, the waiting Indians and fishermen see them rising freely out of the water. Yet much of this leaping is plainly only for sport, and many people claim that salmon actually eat nothing at all during the time that they are going[742] up rivers. These rivers offer a succession of pools and rapids. In almost every pool, during the day-time in summer, there are salmon resting from the labor of stemming the current. It is said that at night they are often to be found on the bars in the shallow rapids above the pools. If the water is low they ascend very slowly, but any rise in the river stimulates them into a rapid movement upward. When they descend rivers, they fall back much of the way tail foremost, although the distance may be over a hundred miles. Even a salmon can be drowned in swiftly running water. Often they make short runs down river, but they quickly wheel about and usually lie with their heads to the current. When they are descending, they are thin and ravenous; but they rapidly gain in plumpness after reaching the sea. In weight the salmon of the Canadian rivers average between twenty and twenty-five pounds. I suppose a season’s catch would hardly average more than twenty pounds, for it would include many grilse of from eight to ten pounds weight, and salmon weighing only five or six pounds more. A thirty-pound salmon is very large, and a forty-pound fish will be talked of throughout the season, although it is said that salmon weighing fifty pounds have been caught in the Restigouche,—one, indeed, was said to weigh fifty-four pounds. The Princess Louise, the daughter of the Queen of England and the wife of the Marquis of Lorne, the former Governor-general of Canada, caught a forty-pound salmon in the Causapscal river, in the province of Quebec, a few years ago. Last summer I employed one of the two canoe-men who were with the Princess at the time, and he had a great deal to say about her skill in handling that salmon. I don’t think he cared much about other members of the royal family, but “The Princess, sir, she was a good un with the rod.” Salmon weighing sixty pounds are taken now and then in Scotch rivers, and a few rivers in England still[743] yield large fish. Sir John Hawkins speaks of a salmon caught in an English river in April, 1789, which was four feet long, three feet around the body, and weighed seventy pounds. There is a story told of a Highlander who hooked a salmon in the River Awe, and played the fish for hours, until night came on without his being able to tire it out. Then, as the fish was sulking quietly at the bottom, he lay down, took the line in his teeth, that any motion might waken him, and went to sleep. The Highlander slept and the salmon sulked until three o’clock in the morning, when some friends of the former came to look for him. With their help he managed to land the fish about daybreak, and it weighed seventy-three pounds. That was certainly a giant, but a salmon weighing eighty-three pounds is reported once to have been sent to the London market. It would be a serious matter for any of St. Nicholas’s readers to make fast to a salmon as large as that. But it will not happen on this side of the ocean.

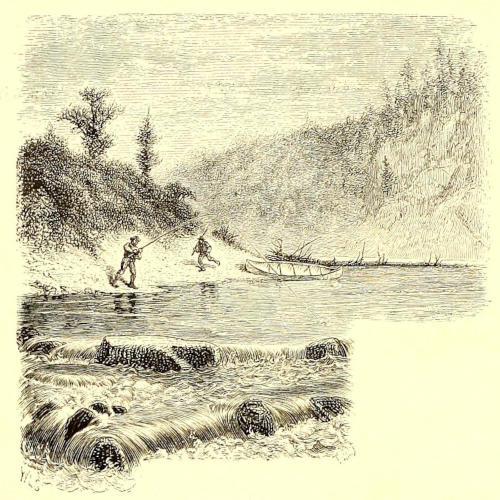

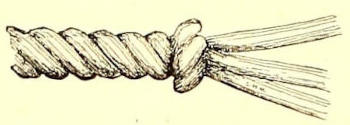

A SALMON POOL.

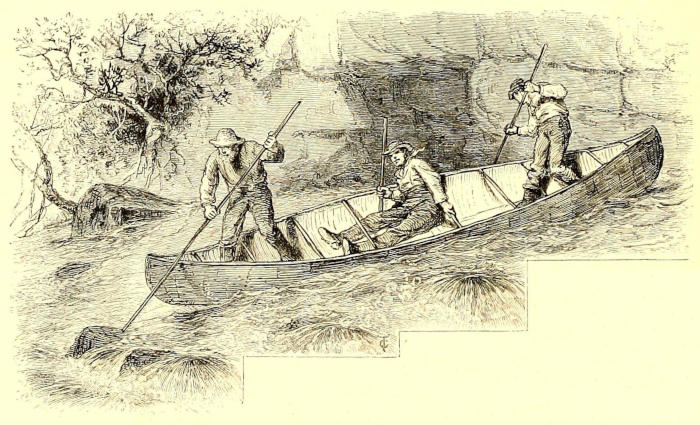

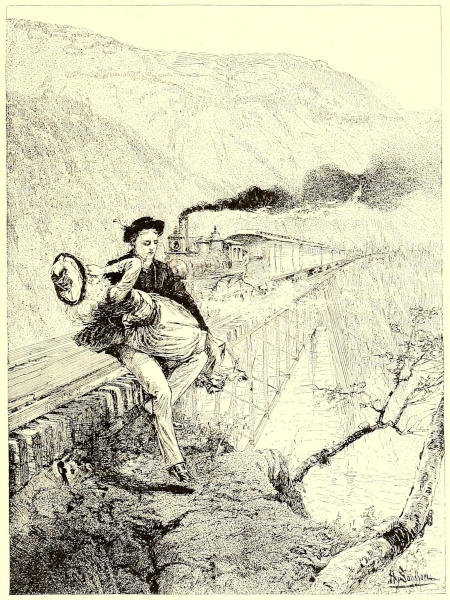

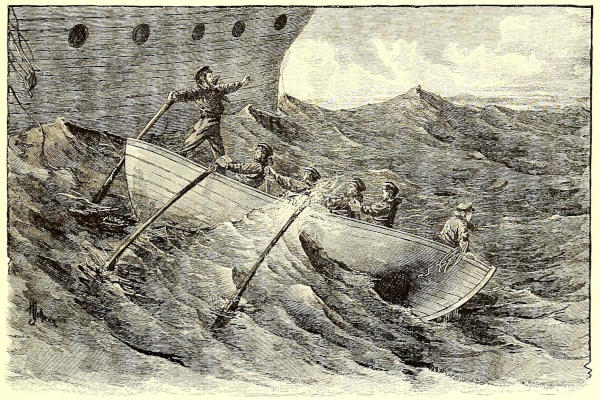

SHOOTING THE RAPIDS.

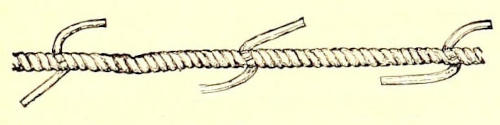

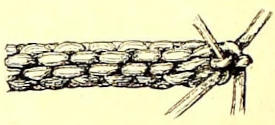

There is only one way in which a true sports-man will catch a salmon, and that is by fly-fishing. But there are a great many other ways, some of which, although unfair, are rather curious. Salmon have been caught with an ax, with a pitchfork, with a wheel, with many forms of nets and spears, by trolling, and by still-bait fishing. Captain Charles Kendall, an old Boston sailor, used to say that he once explored a Canadian salmon river nearly to its head and met a multitude of salmon coming down in water so shallow that their backs were exposed, and he killed scores with an ax, as they tried to rush between his legs. The poor fishes were also attacked by birds of prey. This is the only instance recorded of killing salmon with an ax, but when I visited the valley of the Puyallup River, in Washington Territory, three years ago, I was assured that salmon sometimes crowded that shallow stream so thickly that farmers lifted them out with pitchforks and used them as fertilizers on the field. These, however, were an inferior kind of salmon. One of the most cruel and destructive methods of catching salmon was by water-wheels, at the cascades of the Columbia River. In former times, the Indians gathered at the cascades at certain seasons, picketed their ponies, built wigwams, and remained for days, and often weeks, spearing and netting the ascending salmon all along the shores. But white men found a way of destroying a far larger number of these noble fish. Salmon when coming up the rapids swim near shore. Wheels were built, and suspended partly in the water so that the paddles were rapidly turned by the swift current. The salmon swimming against these paddles were struck with great force, lifted clear of the water, and thrown into tanks arranged near by. The murderous wheels kept on revolving, throwing up every fish within reach, and there was nothing for the owners to do but to gather the quantities of salmon out of the tanks and use them in their salmon-canning establishment. It is not strange that a strong popular feeling soon grew up against this wholesale slaughter.

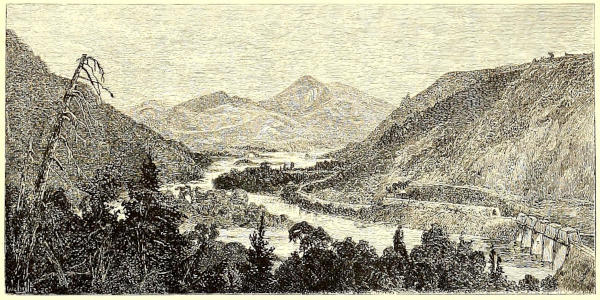

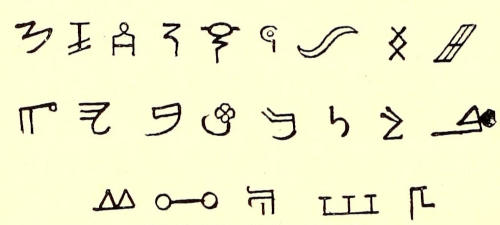

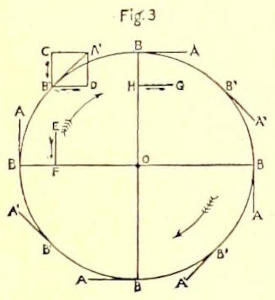

JUNCTION OF THE METAPEDIA AND RESTIGOUCHE RIVERS,—A FAMOUS SALMON POOL.

At the mouth of the same river, the Columbia, net-fishing for salmon is carried on in a larger way than anywhere else on this continent. In the fisheries and canneries nearly seven thousand men are employed—Swedes, Russians, Norwegians, Finns, Italians, Portuguese, Greeks, and Chinamen, a curious mingling of races. Much of this net-fishing is done at night, the sail boats starting from[744] Astoria toward evening and returning in the morning. Sometimes the capsized boats drift ashore alone, for the breakers where the currents of river and ocean meet frequently swamp them, and each season many men are drowned. Between three and four million dollars’ worth of salmon have been sent from the Columbia in a year. In the North-east a great many salmon are caught in nets at the mouths of the St. Lawrence and other Canadian rivers, many more indeed than anglers would allow if they could control the net-fishing. Most of these salmon are artificially frozen and sent to our Eastern markets, where they now have to compete with Oregon salmon. Spearing salmon is very properly forbidden by law in Canada. I have read an account of an odd method of harpooning salmon, which was practiced on a river in the Inverness district in Scotland. At one spot the river falls in a cascade through a narrow cleft in the rocks. Sitting beside this, the fisherman, who had a line attached to his spear, struck a salmon as it tried to leap up, let go his spear, keeping hold of the line, and then, climbing down to the pool below, drew in the exhausted fish at his leisure. This reminded me of an Indian on the Restigouche, who, I was told, used to throw his short spruce pole into the water after hooking a salmon, and paddle after it in his canoe, until the fish was so wearied by dragging the pole about, that the fisherman could easily land it. Still more curious is Sir Walter Scott’s account in his novel, “Red Gauntlet,” of salmon-spearing on the Solway Frith, an arm of the sea between England and Scotland. He describes a company of horsemen riding over the sands and striking with their spears at the salmon which darted about in the pools, where they had been left by the ebbing tide. This kind of salmon-fishing on horseback must have been very like “pig-sticking” in India.

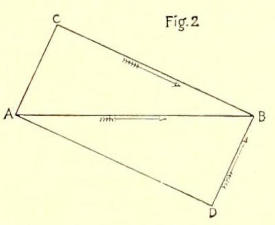

A SALMON RISING TO THE FLY.

On this side of the ocean, trolling for salmon is unknown; there is very little, if any, bait-fishing, and a salmon-spear, in the North-east at least, is only to be found in the hands of a red or white poacher. Poaching on Canadian rivers has diminished, but the law is still broken on the sly; and many odd stories are told of poachers’ tricks. Nearly all these rivers are watched by two sets of wardens. There are the Government wardens appointed to prevent illegal fishing with nets or spears, or out of season, and there are wardens employed by private persons to watch the water which they lease; for every pool in a salmon river is valuable property. Once the Government claimed the fishing privileges, but it was decided that the owners of lands along the rivers controlled the water; and now the farmer’s income from his water is sometimes larger than that from his land; and the limits of each ownership are as carefully marked off as are limits of farms or of town lots. The unlawful act which the wardens most carefully guard against is “drifting.” One or two poachers will steal out at night carrying a peculiarly made net in their canoes. They stretch this across the head of a pool; and it is so weighted and buoyed that it stands upright, reaching nearly to the bottom. As the current causes the net to drift down stream, one canoe stays at each end to keep it straight. There is usually a white rope at the bottom of the net. Seeing this, the salmon raise themselves a little, only to be caught by the gills in the meshes. When the shaking of the net shows that one is caught, the poacher quickly paddles to the spot, raises the net, kills the fish with a blow on its head, and throws it into the canoe. In this sneaking way, nearly all the salmon in a pool may be netted out in a night. If the wardens happen to come along in their dug-outs, they try to seize the net and identify the poachers. Then there may be a fight, and perhaps a canoe will be sunk, and a poacher or a warden will get a cold bath. On one river, the poachers used to station a boy on an island below them, with a horn which he blew whenever the wardens approached. One of the latter was so active that the poachers resolved to punish him. They took an old worthless net and stretched it out into the river from a rock on the bank. A rope was rove through the net and the shore end made fast over a pulley to the traces of a horse. A boy stood beside the horse, and two poachers in a canoe held the outer end of the net. Down came the warden, poling along in his dug-out, and pulled the end of the[745] net away from the seemingly unwilling poachers. He began taking it into his dug-out, congratulating himself on his prize, and had hauled it halfway in, when the boy on shore struck the horse, which started on a full gallop up the bank, jerking the net after it. In a flash the net was pulled out of the dug-out, the latter upset, and the astonished warden pitched into the river. But I hope the poachers were punished in their turn. For if these lawless men had their way, there would be no salmon left in the rivers, and no such glorious sport as fly-fishing.

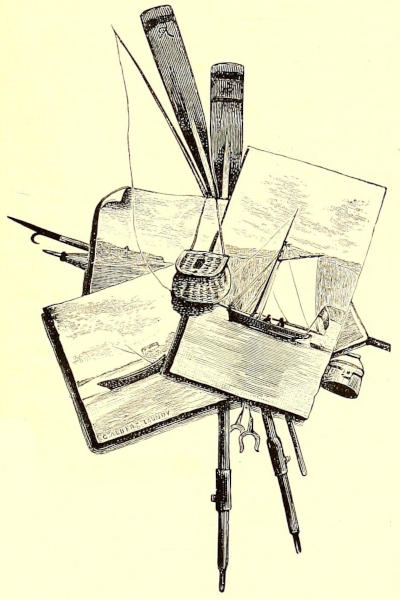

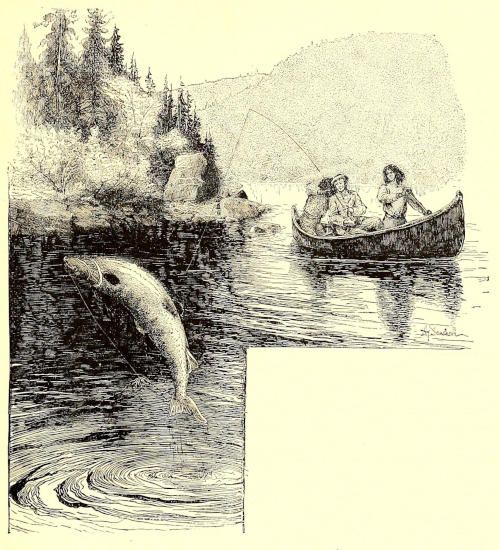

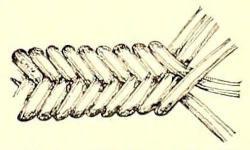

It is for this that hundreds of Americans go away down East every summer. At the junction of the Metapedia and Restigouche rivers are the comfortable buildings of the Restigouche Salmon Club, which is composed of New York gentlemen. In front of the club-house is the finest pool on the river, and the club owns land and water for some miles above. Below, several pools are leased by a small American club, and Americans pay thousands of dollars for fishing privileges on rivers all the way from Nova Scotia to Labrador. Some of my boy readers may have accompanied their fathers or big brothers to Canadian salmon rivers, and themselves landed salmon. If not, I hope they may do so soon.

“RIGHT BEFORE YOUR EYES, THE GREAT FISH LEAPS FOUR FEET FROM THE WATER.”

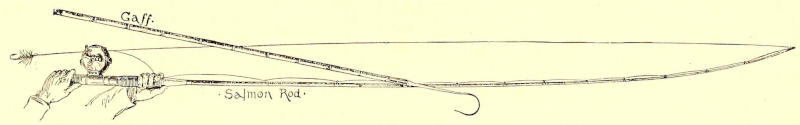

For this fishing, a boy should use a rod not over sixteen feet long, and weighing about twenty-seven ounces. Split bamboo is the finest material, but satisfactory rods are made of ash and lancewood or greenheart. The heavy reel holds a hundred or a hundred and fifty yards of braided silk line. Usually a gut leader, also called a casting-line, which is about nine feet long, is fastened directly to the silk line. Only one of the large gaudy salmon flies is used on the leader at one time. Suppose yourself thus equipped, sitting in the middle of a cranky birch-bark canoe, on the Restigouche, with an Indian at the bow and another at the stern, paddling to the head of a salmon pool, as the morning mists rise from the mountains. Just below the rapids, the Indians turn the canoe into midstream and drop the anchor, which clinks musically upon the stones of the bottom. You take up the rod, which will[746] seem awkward if you have been using a seven or eight ounce trout-rod, and holding it in both hands, one above and one below the reel, begin to make short casts in front and on either side. It is always well to whip the water near the canoe, for there is no telling where a salmon may be. Once I looked down over the side of my canoe into the very eyes of a large salmon. He lay at the bottom, looking up at me for a moment, then flirted his tail scornfully and disappeared. I should like to have seen more of him. You will lengthen out the line a few feet at a time, as you continue casting, and you will always keep the point of your rod moving a little up and down, so that your fly shall be in motion in the water. Possibly the longed-for salmon will jump out of water at the fly. If so, he will probably miss it. More likely, you will suddenly see a mighty swirl in the water, catch a glimpse of a head, perhaps, and feel a tug—at least you are likely to, if you “strike” when you see the swirl.

Then all in the same instant the reel begins to scream and your heart to beat like a trip-hammer. Up comes the anchor, the Indians paddle over to one side of the river, and you manfully keep the rod pointing upward, clutching it with your left hand above the reel, the end of the butt pressed against your waistcoat buttons, and your right hand ready to reel in line if the fish comes toward you or sulks at the bottom.

All at once something happens which takes away your breath. Right before your eyes the great fish leaps four feet from the water, his writhing body curved like a silver bow, and glistening in the sunlight until he falls back with a splash that almost makes your heart stop beating, for fear he has broken loose. But no! You instinctively lowered the tip of your rod when he jumped, and he did not fall upon a taut line, as he hoped, and break away. The reel screams again as the salmon darts off down river; and as the canoe-men paddle after, you think of the Indian who lassoed the locomotive. Perhaps he will rush through the lower rapids into the pool below. Never fear! He is well hooked, and the strain of the rod is telling. Backward and forward he darts, while the line cuts the water, now sulking quietly, again startling you by a wild leap. At last he begins to yield. The canoe-men paddle you to a beach where you cautiously step out, keeping your face to the foe. Slowly, carefully you reel in line, straining the fish toward you. The Indians wait with the gaff, a large steel hook in the end of a stout pole. Now the salmon makes a despairing run, then, growing weaker, he obeys your strain. You can see him plainly as he comes into shallow water. What if you should lose him now! The Indians, bent double, ankle-deep in water, watch his every motion. One strikes at him, but misses, and the gallant fish makes another fight for life. But now he is within reach. The gaff is raised carefully, you hold your breath, and this time the steel pierces that silvery side, and out of the foaming water the gaff draws a noble salmon, your first—and let me hope a forty-pounder. Perhaps twenty minutes have passed since you hooked him,—perhaps an hour; but you have lived an age.

May all the boy readers of St. Nicholas some time know such thrilling sport as this! And the girls, too, may emulate their brothers, and each some time land a salmon. At least they can have the sport without holding the rod. One of the prettiest sights which I saw on the Restigouche was the eager face of a little girl in a canoe, with her father, who was fighting a twenty-five-pound salmon. Looking at her parted lips and wide-open eyes, I felt sure that girls as well as boys could feel the fascination of that most exciting of all forms of angling, salmon-fishing.

[2] Verrazani, a Florentine navigator, is now believed to have been the original discoverer of the Hudson, about 1525.

[3] About three hundred thousand salmon fry have been planted in the upper waters of the Hudson each year, since 1882. In 1884, a salmon weighing four pounds was taken near Hudson, New York, and several yearling salmon were caught, a year ago, in a stream tributary to the Hudson. Last spring, a salmon weighing ten pounds was taken in Gravesend Bay, and there have been other similar results from the work done by Mr. Fred Mather, Superintendent of the New York Fish Commission, in charge of the station at Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island. It is thought that the Hudson was never much frequented by salmon for the purpose of spawning, on account of Cohoes’ and Miller’s Falls. But the fish were formerly taken near the mouth of the river, and it is hoped that the entire river may be made a salmon stream, if it will “grow salmon,” by the construction of fish-ways which will enable the salmon to ascend the falls. Professor Baird, the United States Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries, restocked the Connecticut, where no salmon had been for twenty-five years, with such success that “Connecticut River salmon” were regularly quoted in the markets. But the fishermen caught out the spawning fish and foolishly depopulated the river so that the work was stopped, although I understand that another effort has been made recently. In the Penobscot River, in Maine, salmon have been hatched and cared for, until, this very season, there has been excellent salmon fishing in the neighborhood of the city of Bangor.—R. H.

By A. R. Wells.

For two days following that bright morning in September, the skies dropped discouragement on all enthusiasms, and dampened any ardor for aggressive change. What feminine heart has the courage to go forth gloriously to conquer or to die—in overshoes and a gossamer?

In the meantime, the girls had not met again, but new thoughts sprouted in their brains, while feeble plans budded and dropped unfruitful from the bough.

Nan lighted a fire in the grate in her room, and re-read and burned package upon package of old letters, tossing away with special vigor all those tied with that badge of sentimental girlhood—a blue ribbon. Why always blue?

“There!” she exclaimed, as the last mouse-colored fragment fluttered up the chimney; “there is nothing like beginning again at the foundation, in every way.”

This heroic sacrifice completed, she sewed on some loose shoe-buttons with as much vigor as though she contemplated setting out on foot to seek her fortune. After that, she pressed her forehead against the window-pane, and wished drearily that it would stop raining.

Evelyn, after an hour’s interview with her mother, began to rip up an old dress, though she was evidently busied also with serious thoughts.

Cathy, left to herself, and without the stimulating influence of her friends, decided with placid regret that there was no way to improve her existence; she felt like the man who tried to lift himself over the fence by pulling at his boot-straps.

Bert shut herself up and wrestled with a long column of very symmetrical figures. The result of the addition seemed to dismay her. She clutched her bang with one hand, while she carefully went over the list again.

Bert had lain awake hours and hours the night before, rehearsing the various parts she might assume as a lady-like peddler of different wares to a paying public; but she surveyed her small pack of accomplishments with the sad conviction that she “hadn’t a faculty that anybody would give two cents for.” “If some one would kindly hire me to read all the new novels, or should desire my services as assistant hostess at endless dinners and luncheons, I think I might command quite a salary,” sighed she, knowing well her own self-poise and general success in those unremunerative employments.

“Or, there is my other little stock-in-trade,” she continued with disconsolate amusement—“writing letters! I do think I can write a letter.”

And she could, because she always wrote with the keen mental enjoyment of exercising her own fluent powers of expression. “But,” she reflected, “who is going to pay my dress-maker for the intense pleasure of being allowed to receive my epistles? No, letter-writing hasn’t any market value—But—but hasn’t it?”

Ah, now she was really thinking! For she sat motionless, with raised eyebrows and parted lips; then she started to her feet, walked excitedly up and down her room a few times, surveyed herself in the glass, and laughed and chuckled in a mysterious way as she put on her overshoes and hoisted her umbrella.

Mr. Mitchell was a very busy man—too busy to know his daughter very well; and, as is far too common with busy men, he regarded a girl as an entirely useless, rather expensive but withal pleasant factor of his establishment. So, as may be imagined, he was somewhat surprised as he sat in his private office on that particular drizzly day, hurriedly writing a business letter, when Bert, bright and emphatic, suddenly appeared.

Her father, without stopping his rapid pen, looked up, between sentences, long enough to say with good-natured bewilderment, “Why, Bert, what has brought you here? Do you need some more money?”

Bert flushed at that question. Some thoughts with which she had been exercising her mind had made it a trifle sore; and in the mood occasioned by those thoughts, her father’s evident surprise at her appearance, his slight emphasis on “here,” and his seemingly natural conclusion as to the cause of the phenomenon, rather hurt her feelings.

“Money?” she said, with some heat, “No, sir! Do you regard me as only a creature with an all-devouring greed for gold?”

Then, laughing pleasantly as she deposited her umbrella in the rack, she added, “No, Papa dear, not just now. I thought you would be going home soon and I’d like to walk up with you.”

Mr. Mitchell paused a moment, in the act of clapping on another stamp, to survey his tall daughter through his eye-glasses.

“Eh! That’s good. I can’t go for half an hour though—six or seven more letters to write.”

He said this a little wearily, and proceeded to date another sheet of paper, running his left hand through his thin hair, as though he had already forgotten his daughter’s presence in the absorbing nature of his relations with “Messrs. Hutton, Wells & Co.”

Bert sat down in an office chair and looked about her. Not that she had never been in her father’s office before, but never before had she looked at it with the same mental vision that now surveyed the dingy windows, dusty writing-desk, and generally unkempt and dismal aspect of the place where her father spent so much of his life.

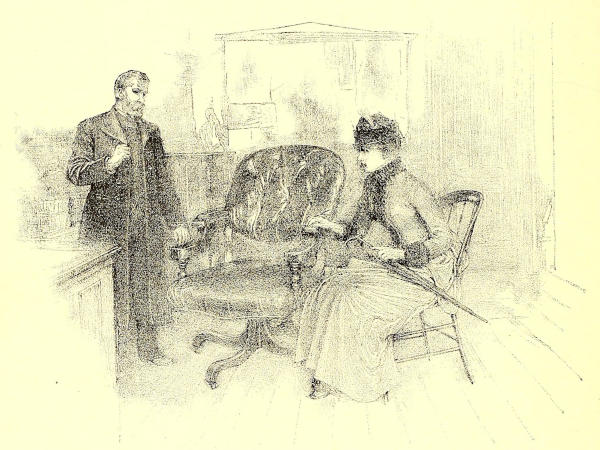

BERT AND HER FATHER HAVE A BUSINESS INTERVIEW.

“Dear me,” she thought, “how soon I could brighten up things! I wonder if he would like it if I should try?”

Presently Mr. Mitchell collected a heap of letters, shut up his inkstand, and wheeled his chair slowly about, as he carefully counted them over.

Bert, who had been contemplating in her mind’s eye the effect of a rug on the floor, looked up and remarked, “What a lot of letters!”

“Yes,” answered her father with a sigh, “since Nelson went I have had my hands full. It is hard to fill his place.”

“Why?” asked Bert, with interest.

“Because,” said Mr. Mitchell slowly, “good stenographers do not grow on every bush; and it is difficult to find any one to whom I can intrust my private correspondence.”

He took his coat from the hook and slowly put it on his shoulders, while Bert sat still, looking very lugubrious.

“Oh,” she said slowly, “would your amanuensis have to know short-hand?”

“Of course,” her father replied, looking somewhat surprised at the unusual interest in such affairs exhibited by his brilliant daughter, of whom he had perhaps been rather more proud than fond.

“You see,” he continued, “I might as well write them myself as wait for him to write out my dictation in long hand.”

Mr. Mitchell stepped into the general office to[751] give a direction to one of the many clerks, all of whom were getting their hats with great promptness as the minute-hand neared six.