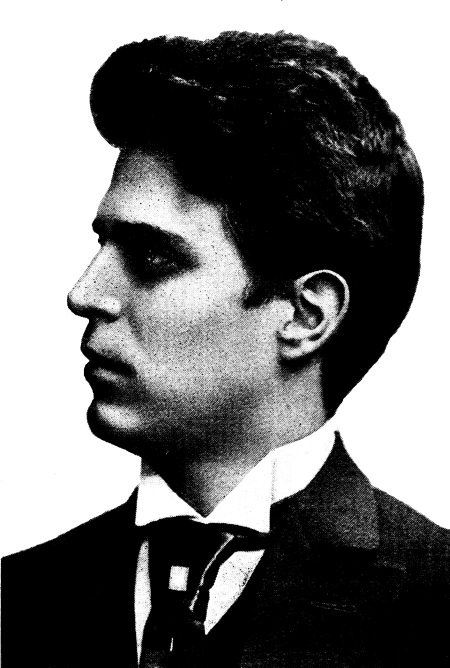

Sir Arthur Sullivan, M.V.O., Mus. Doc.

Painted by Sir John Everett Millais, Bart., P.R.A.

The Music Story Series

Edited by FREDERICK J. CROWEST.

The Story of Opera

The Music Story Series.

3/6 net per Volume.

Already published in this Series.

This Series, in superior leather bindings,

may be had on application to the Publishers.

[ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

Sir Arthur Sullivan, M.V.O., Mus. Doc.

Painted by Sir John Everett Millais, Bart., P.R.A.

MASCAGNI.

BY

E. Markham Lee

M.A.; Mus. Doc., Cantab.

London

The Walter Scott Publishing Co., Ltd.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons

1909

HistorieS of Opera are not very numerous: there have been many articles and essays in various magazines, dictionaries, and so forth which have presented more or less concise synopses of the gradual development and growth of the Operatic Art. Some of these, notably the one in Grove’s Dictionary, are excellent, but a work of such bulk is not for the everyday reader, nor, generally speaking, for the amateur. Beyond these magazine and dictionary essays the number of books—at any rate in the English language—solely on Opera is very limited, and from the nature of the case, those that exist soon get out of date.

In the present work an attempt has been made, so far as space has allowed, to give some brief account of every notable School of Opera of which anything is known. It is not claimed that the advance of the Art will not necessitate constant additions to or alterations of these pages. Even in the short space of time that has elapsed since the body of this book on Opera was written, such features as the rise in [Pg vi] popularity of Puccini’s operas, or of such modern works as Debussy’s Pelleas and Melisande, the permission of the censor to play Saint-Saëns’ Samson and Delilah on the English stage, and the slight wane in interest on the part of the English public for Wagner’s operas, have made imperative the rewriting of many paragraphs and the modification of others.

Every attempt, however, has been made to bring the book up to date, and if in the Chapters on Modern Operas and in the Appendices there may be omitted names which some may consider should have been included, it must be borne in mind that in the twentieth century opera composers spring up like mushrooms, and often disappear from public gaze with equal rapidity. Works of bygone generations can be criticized and placed as successes or failures, but in these days of strenuous output one cannot speak with any certainty as to what is ephemeral and what is enduring. Our own times are too close to us, and must be left for future historians to pronounce judgment upon. Hence only the most notable and brilliant successes amongst modern operatic works are, generally speaking, recorded.

It is hoped that the Chapters on “What is Opera?” and “How to listen to and enjoy Opera” may touch to some extent on new ground and may be [Pg vii] helpful to the amateur. Appendix A has entailed an enormous amount of work, and although it contains, of course, nothing that cannot be gathered from other sources, it is trusted that the information thus compiled and placed under one heading may be of use and of interest to the student of Opera. The tabulated State Grants in Appendix B will show, what is perhaps not generally known, how badly off England is in this matter as compared with many other countries.

The book is offered in all sincerity to those who care to read it. There are, possibly, mistakes and errors. If this be so, I will ask my good friends to point them out to me, in the hope of my having an opportunity of availing myself of such corrections in a second edition of this work.

Woodford Green,

November 1909.

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| WHAT IS OPERA? | ||

| PAGE | ||

| What is Opera?—Derivation of term—A musical work—An | 1 | |

| artificial product—Its justification—Emotional effect | ||

| of music—Hybrid opera—Modern taste demands one | ||

| medium of expression—A definition—Music an | ||

| accessory to opera, but an important one | ||

| CHAPTER II. |

||

| DIFFERENT SCHOOLS CORRESPONDING WITH THE GROWTH OF MUSICAL ART. |

||

| The centuries see little change in the elements of the |

7 | |

| drama—Growth of opera concurrent with the progress | ||

| of the art of music—Points of difference between | ||

| early operas (Monteverde, etc.) and those of Scarlatti | ||

| and later writers—Birth of the aria—England and | ||

| France of the same date—Opera buffa—Musical | ||

| empiricism—Gluck—His followers—Varying subjects | ||

| treated—Italian opera—Abuses by the singers—Wagner | ||

| and modern opera | ||

| CHAPTER III. |

||

| THE REFORMERS OF OPERA: MONTEVERDE, GLUCK, AND WAGNER. |

||

| Reforms, and the reasons thereof—Monteverde’s |

18 | |

| influence—Musical innovations—The stage discards music | ||

| of the ecclesiastical order—The beauty of Scarlatti’s [Pg x] | ||

| arias—Their weakness—Gluck—Gluck’s explanation of his | ||

| reforms—Triumph of his methods—Another retrogression— | ||

| Rossini—Wagner—The leit-motif—Influence on subsequent | ||

| composers—Will further reforms become necessary, and | ||

| what shape will they take? | ||

| CHAPTER IV. |

||

| THE BEGINNINGS OF OPERA. | ||

| Early commencement of opera—The Bardi enthusiasts—What |

32 | |

| they achieved—Peri and Caccini—A logical | ||

| commencement—Its imperfections | ||

| CHAPTER V. |

||

| EARLY ITALIAN, FRENCH, GERMAN, AND ENGLISH OPERA. |

||

| Monteverde—Scarlatti—Cambert—Lully—Keiser—Purcell—Handel |

39 | |

| in London—Handel’s rival, Buononcini—Handel’s operas now | ||

| obsolete by reason of their lack of dramatic truth | ||

| CHAPTER VI. |

||

| THE OPERAS OF GLUCK AND THE GREAT COMPOSERS. |

||

| Gluck and his masterpieces—Mozart—Beethoven—Weber |

48 | |

| and romantic opera—Der Freischütz—Other operas— | ||

| Schubert—Opera writing a distinct form of composition | ||

| —The small influence of the really great composers | ||

| upon opera | ||

| CHAPTER VII. |

||

| SOME LESSER STARS IN THE OPERATIC FIRMAMENT. | ||

| (a) THE ITALIAN SCHOOL (CIMAROSA TO VERDI). |

||

| The Italian school--Opera buffa--The Neapolitan school— |

63 | |

| Piccini—A notable contest—Cimarosa—Rossini: his | ||

| Barber of Seville—Recitative and its significance— | ||

| William Tell—Bellini and Donizetti— Verdi: his | ||

| early and later operas [Pg xi] | ||

| CHAPTER VIII. |

||

| SOME LESSER STARS IN THE OPERATIC FIRMAMENT. | ||

| (b) THE GERMAN SCHOOL (KEISER TO NICOLAI). |

||

| Keiser and his successors—Hiller—Real German opera— |

76 | |

| Spohr—Marschner—Operatic interest not centred | ||

| in Germany at this time | ||

| CHAPTER IX. |

||

| SOME LESSER STARS IN THE OPERATIC FIRMAMENT. | ||

| (c) THE FRENCH SCHOOL (RAMEAU TO AMBROISE THOMAS). |

||

| Rameau—Divergence of methods—The successors Piccinni— |

81 | |

| Méhul—Cherubini and of Gluck and Spontini— | ||

| Meyerbeer—Auber—Gounod—Bizet—Reasons for | ||

| the popularity of Faust and Carmen—Offenbach— | ||

| Délibes and Lalo—Thomas | ||

| CHAPTER X. |

||

| ENGLISH OPERA OF THE EIGHTEENTH AND PART OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY. |

||

| The Beggar’s Opera—Arne—Bishop—Balfe—Wallace—Goring |

91 | |

| Thomas—Sullivan—Living writers | ||

| CHAPTER XI. |

||

| WAGNER AND HIS OPERAS. | ||

| Wagner’s early days—At Würzburg—At Königsberg—At Riga—At |

98 | |

| Paris—Rienzi—Dresden—Zurich—Munich—Triebschen | ||

| —Bayreuth—Death—Wagner’s methods—The Flying Dutchman— | ||

| Tannhäuser—Lohengrin—Tristan and Isolde—Die | ||

| Meistersinger—The Ring—Parsifal—Wagner’s | ||

| continued development [Pg xii] | ||

| CHAPTER XII. |

||

| MODERN OPERA SINCE WAGNER’S REFORMS. | ||

| Wagner’s influence—No mere copying—Modern “Melos”—Use |

116 | |

| of the orchestra—His harmony—Men of a younger generation | ||

| —The Slavs | ||

| CHAPTER XIII. |

||

| SLAVONIC OPERA. | ||

| Early Russian composers—Glinka—Dargomijsky—Borodin—César-Cui |

122 | |

| —Tchaïkovsky—Polish opera—Bohemian opera—Dvôrák | ||

| —Other European countries | ||

| CHAPTER XIV. |

||

| OPERA TO-DAY IN ITALY, GERMANY, FRANCE, AND ENGLAND. |

||

| Boito—His interesting personality—Puccini—Mascagni— |

130 | |

| Leoncavallo—Cilea—German composers—Goldmark and | ||

| Humperdinck—The French school—Saint-Saëns—Massenet | ||

| —Bruneau—English composers—Stanford—Mackenzie— | ||

| Cowen—Corder—Bunning, etc. | ||

| CHAPTER XV. |

||

| OPERATIC ENTERPRISE IN ENGLAND. | ||

| Subsidized opera—Opera an educative factor—Objections to |

150 | |

| subsidies—Advantages—English opera—Opera companies | ||

| —Covent Garden—The Royal Opera Syndicate—History of | ||

| opera in this country—Travelling companies—The Carl Rosa | ||

| Company—The Moody-Manners Company—The outlook [Pg xiii] | ||

| CHAPTER XVI. |

||

| HOW TO LISTEN TO AND ENJOY OPERA. | ||

| Feelings of disappointment—Expectations—The language |

163 | |

| difficulty—Why the story is hard to follow—What we go | ||

| to the opera to hear—Some suggestions—To grasp the | ||

| story—To realize the style of the music—Re-hearing | ||

| necessary—How to begin to study opera—What is | ||

| necessary for its enjoyment | ||

| CHAPTER XVII. |

||

| THE CHIEF OPERA HOUSES OF THE WORLD. | ||

| Covent Garden—La Scala—San Carlo—Venice—Rome—Paris and |

172 | |

| the Grand Opera—Vienna—Budapest—Prague—Berlin—Dresden | ||

| —Munich—Bayreuth—Russia—Other European countries— | ||

| Egypt—America | ||

| CHAPTER XVIII. |

||

| OFFSHOOTS AND CURIOSITIES OF OPERA. | ||

| Operetta—Musical comedy—Ballad opera—Masque—Ballet— |

185 | |

| Objections thereto—Curiosities of construction— | ||

| Pasticcio—Mixed language—Stereotyped casts—Curiosities | ||

| of stage requirements—Wagner’s supernatural requirements | ||

| —Curiosities of the music—Vocal cadenzas | ||

| CHAPTER XIX. |

||

| A CHAPTER OF CHATTER. | ||

| Opera and politics—Lohengrin inParis—Opera non-lucrative to |

199 | |

| the composer—Jenny Lind’s contract—Modern fees— | ||

| Royalties—Librettists—Metastasio and Scribe— | ||

| The prima donna—Stories of singers and composers [Pg xiv] | ||

| Appendix A.—Chronological List of Composers of Opera, |

||

| Great Singers, Conductors, etc. | 215 | |

| Appendix B.—Financial Aid Granted to Operatic Schemes | ||

| from State or Municipal Funds | 248 | |

| Appendix C.—Glossary of Terms mainly used in Opera | 255 | |

| Appendix D.—List of Instruments used in the Orchestras of | ||

| Composers of Different Periods of Opera | 260 | |

| Appendix E.—Bibliography of Opera | 263 | |

| PAGE | |

| SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN | Frontispiece |

| Photogravure from the Painting | |

| by Sir John Everett Millais, P.R.A. | |

| ALESSANDRO SCARLATTI | 20 |

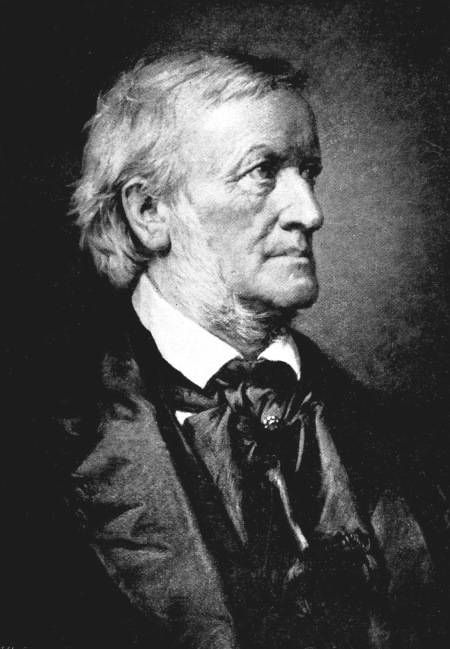

| RICHARD WAGNER | 26 |

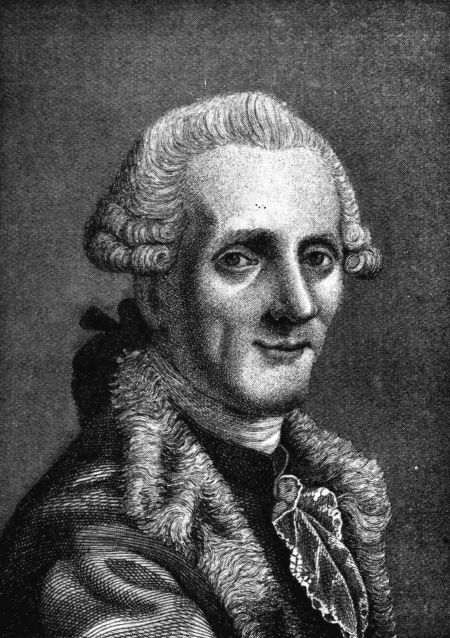

| JEAN BAPTISTE LULLY | 42 |

| DOMENICO CIMAROSA | 64 |

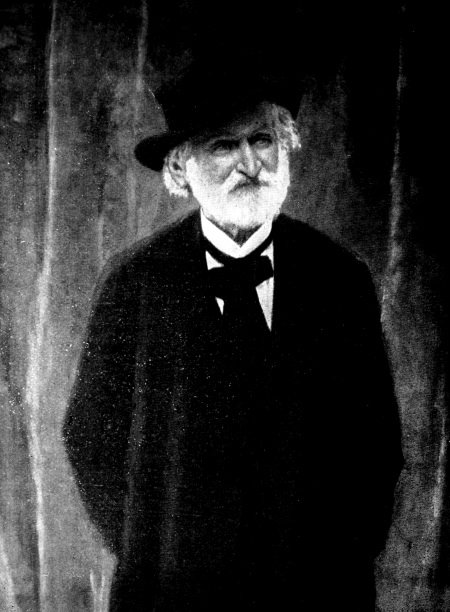

| GUISEPPE VERDI | 72 |

| JOHANN ADAM HILLER | 78 |

| NICOLA PICCINI | 82 |

| J. OFFENBACH | 88 |

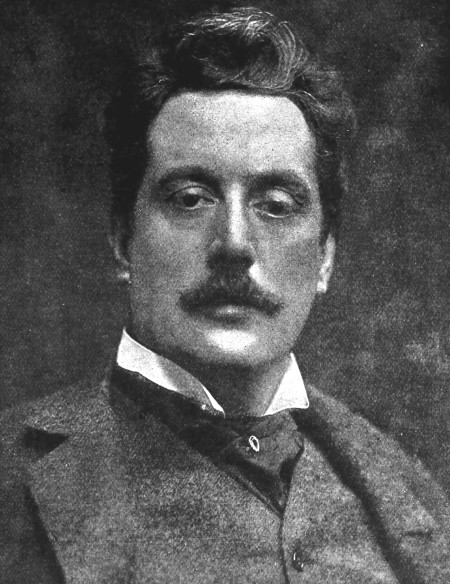

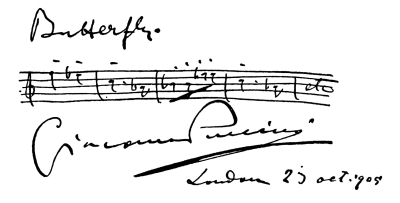

| GIACOMO PUCCINI | 130 |

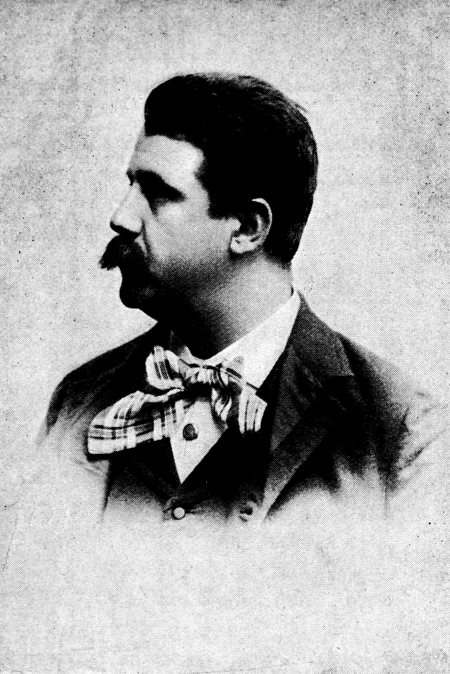

| PIETRO MASCAGNI | 132 |

| RUGGIERO LEONCAVALLO | 136 |

| SIR A. C. MACKENZIE | 146 |

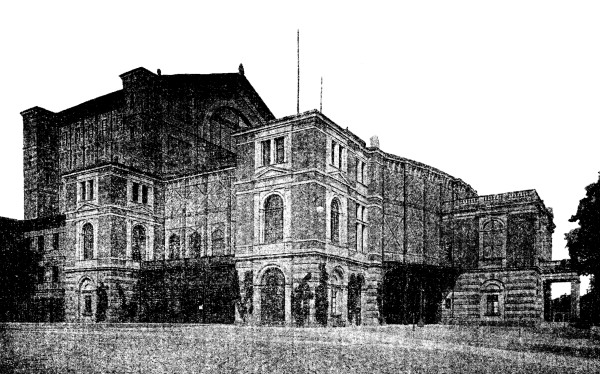

| BAYREUTH THEATRE | 181 |

| MADAME MELBA | 200 |

What is Opera?—Derivation of term—A musical work—An artificial product—Its justification—Emotional effect of music—Hybrid opera—Modern taste demands one medium of expression—A definition—Music an accessory to opera, but an important one.

What is Opera? A question easy to ask, but one that by no means finds so ready an answer; the definitions, “A drama set to music,” “A musical play,” and so forth, being but loose and inaccurate, and not conveying any real idea as to that which they seek to define.

The term “Opera,” derived, or rather abbreviated from the words “Opera in Musica” (Works in music—i.e., a musical work), may be at once seen to be only a convenient title that has found favour by its brevity and through lack of a better: translate it and read “works,” and we may see that it is a meaningless term in all else than that it is something created. [Pg 2]

And what is this “something” that has been created, that is in people’s mouths so often, and that we designate by the word “Opera”? The least cultured will be able to answer that it is a work for the stage, in which music plays a prominent part: that it is this, and something more, must be shown as we study its rise and development.

Let us go a little deeper in our search for a definition. In studying real opera we shall find that not only is it a dramatic production, and that music plays an important part in it, but that any spoken dialogue is foreign to its nature. It is therefore a continuous musical work, uninterrupted by speeches or sentences spoken by the natural voice—sung throughout, the music being illustrative of the story that is being unfolded, and accompanied by appropriate gesture and action. Evidently, then, Opera is a very artificial production; for although under some circumstances one may indeed burst forth into spontaneous song, it is difficult to imagine any considerable number of connected incidents or episodes in one’s life which would naturally suggest music, to which music would be a fitting accompaniment, or which would demand vocalized words for the adequate expression of the sentiments aroused by them. [Pg 3]

Fierce rage, passion, death agonies, jealousy, quarrelling on the one hand, and wit, humour, ordinary dialogue on the other—instances of these are more or less commonly met with in our ordinary experiences, and as such they are frequently and naturally reproduced on the stage. But feelings or emotions called up by such events are by no means naturally expressed by musical sounds; and yet in opera we find such emotions, such conditions frequently constituting some considerable portion of the subject-matter of the piece; and since all is sung, it follows that musical expression of these emotions must necessarily be rendered.

Opera, then, must be admitted to be a thing of artificiality. Some will say, “Since the introduction of music into a dramatic work admits an unreal element into that which might otherwise receive a natural interpretation, how can its existence be justified?”

The answer to this is, that whatever may be the feelings or actions to be expressed by the stage characters, proper and suitable music will express them with far greater intensity and far greater power than will spoken words or mere gesture. Such are the emotional qualities of the art of music that a phrase of quite ordinary significance in words may [Pg 4] become, if wedded to expressive music, a thing of beauty and life; an emotional feeling may be roused in the auditor that the mere spoken word could never have touched. In the case of words that may themselves contain beautiful ideas, their loveliness can be greatly enhanced by the addition of music, their meaning intensified, their impressiveness doubled.

Artificial, then, as Opera is, and must be, it can justify its artificiality: a drama is put upon the stage, and in order that its situations, its sentiments, and its meaning may be more fully expounded, music is called in to elucidate, to express, and to beautify. Admitting the possibility of this—which no one who has the least feeling for music, or who is at all moved emotionally by the art of sweet sounds, can deny—we find that Opera justifies its existence, despite its unreality and its unlikeness to life.

But all Opera is not sung throughout: there is a large number of musical works under this name having spoken dialogue. Justification for these is more difficult, for it may be readily understood that one form of expression should be used throughout, and that this modified form of Opera (known as Singspiel), being neither one thing nor the other, is a hybrid form, which really has no right of admission to the title of [Pg 5] Opera at all. The fact that it is often effective and highly popular hardly excuses its violation of art form. Of this more anon, for so many plays of this kind with musical numbers were written at a certain period of the history of the art and were classed as operas, that their claims cannot be overlooked. But modern taste in opera demands that one medium of expression be made use of throughout, and thus a return has been made to the early and more artistic form of “Opera in Musica”—the true form, of which the Singspiel is only an offshoot.

We may answer our question, then, “What is opera?” in some such manner as this: An opera is a play designed for the stage, with scenery, costumes, and action used as accessories as in all stage plays, but with the additional use of music to intensify the meanings of the lines which are uttered by the characters, to generally heighten the effect produced by the other combined arts, and to add an emotional element that might otherwise be lacking.

Let us notice that music is only an accessory to the play: an important one, it may be granted, but yet only an accessory. It has been through failure to recognize this limited position of music in opera that [Pg 6] accounts for thousands of operas never being heard now. The exaltation of the music at the expense of plot, action, and dramatic fitness has caused the downfall of many a promising operatic composer. Public taste has been to blame, but in the long run it has always veered round to a proper appreciation of the truly artistic; it has made many mistakes, but sooner or later, guided by some master mind, it has discarded the false and taken to the true and real form of opera, with the result that most operas written to-day are consistent wholes, dominated by one general idea, and written upon one fixed governing principle.

Opera, then, generally speaking, is an Art form, in which a stage play is presented with all usual accessories, but with the important addition of continuous music: this is a general definition, but one of which there are so many modifications that we must turn aside for a moment to trace how it happens that so many forms and varieties of opera as there seem to be have sprung into existence.

The centuries see little change in the elements of the drama—Growth of opera concurrent with the progress of the art of music—Points of difference between early operas (Monteverde, etc.) and those of Scarlatti and later writers—Birth of the aria—England and France of the same date—Opera buffa—Musical empiricism—Gluck—His followers—Varying subjects treated—Italian opera —Abuses by the singers—Wagner and modern opera.

The changes that have taken place in opera during the short three hundred years which constitute the life of modern music are far more prominent and important than those that have been undergone by the ordinary dramatic work: the arts of elocution, gesture, and stage action are very old ones, and have seen little radical change for many centuries. Great progress has been made through the use of modern mechanical devices and inventions in the mounting of all stage pieces—i.e., in the scenery employed, the lighting, and stage [Pg 8] effects generally: these all appeal to the eye; but the appeal to the ear is not, in an ordinary dramatic work, more powerfully made than it was in the days of the Greek dramatist. But when music is added, then appeal to the ear of a most powerful kind takes place, and during the whole life of the youngest of the Arts the improvements and growth in musical technique and expression have been grafted upon opera with continuously progressive power and effect.

Now, since opera has demanded for its representation an art that has been in a state of continuous growth, it will follow that the different classes of opera will closely correspond with the different styles and schools of music: we shall find therefore that the earliest operas were only able to employ crude and undeveloped music, none better being available; that as musical skill and knowledge grew, as additional instruments were added to the orchestra, as knowledge of forms developed, so all these improvements found their way into operatic music, with the result that the difference between say a seventeenth and an eighteenth century opera is a very wide one, while a vaster difference still may be seen between one of the eighteenth and one of the late nineteenth century. [Pg 9]

We may briefly examine the causes of these differences, taking the dawn of all modern music (about 1600 A.D.) as the starting-point.

If we take the operas of the first few years of the seventeenth century, what do we find? That the form of tonality in use was the mode and not the scale; that time (i.e., measured music), as we now know it, did not exist; that harmony, as we now know it, did not exist; and that the instruments of the orchestra (although some have survived), were in the main instruments which have fallen into disuse, many of them having no modern counterparts. It needs little pointing out that this form of opera must have sounded very different to its successors.

The next important innovations, generally accredited to Monteverde, include the dramatic effects of pizzicato and tremolo passages for the stringed instruments—devices which have been used with the happiest results by all composers of subsequent date. Such devices, unknown in church music anterior to this time, or even in the music written for instruments only without voices in the church style, are most effectively employed for the illustration of certain situations on the stage: the mere introduction of these alone is sufficient to separate this school of opera from that which preceded it. [Pg 10]

But Monteverde’s inventions or adoptions did not stop here, for it was he who first added many instruments to the orchestra; not only did he employ additional instruments, but he used them in such a way as to wed certain characters or situations to music in which certain sets of instruments were employed, thus anticipating the much later Wagnerian device of accompanying certain ideas by a fixed theme, or by particular combinations in the orchestra.

So far the music of the opera was confined to recitative: that is, to the musical rendering of the dialogue without regular rhythm or melody. Another period of opera opened out altogether, when composers began to adapt portions of the dialogue to regular formal melody of a rhythmic nature, and in the diatonic scale, much as we now know it.

Credit for this is generally given to Cavalli, and his example was followed by a well-known early opera writer, Alessandro Scarlatti. The recitative of the latter took, too, a richer shape and form, inasmuch as it was now often accompanied by the whole of the orchestra, instead of merely by the continuous bass, completed by harpsichord harmonies.

Scarlatti, however, may claim a more still important innovation, the [Pg 11] adoption of set forms: his ideas were often cast into lyrical shapes, his solos were often arias of definite mould, and above all, he deliberately adopted the Da Capo Aria in the majority of his works. This Da Capo Aria would be described by a student of modern form as a “Ternary” movement, in so far as its first part was entirely repeated after the performance of a contrasted middle section. That Scarlatti’s invention killed itself by its own popularity is a matter to be spoken of elsewhere: suffice it to notice that the introduction of the “Da Capo” Aria brought into existence a new form of opera, different to all that had gone before.

Meanwhile opera was progressing in Germany, France, and England, each school having certain distinguishing characteristics. Purcell’s work in England was unlike that of any Continental opera composer, and his melodies have a boldness, freedom, and ring about them quite their own: English music of the period was a reflex of the national character, straightforward, honest, and vigorous. At the same time, Lully in France was developing quite another side of opera, by the introduction of the ballet, a form that has been retained till within quite recent times by the French.

Handel, although the success of his operas killed, for the time being, [Pg 12] all English-born ideas, added little or nothing to the forms of Scarlatti; he practically left opera where he found it, nor were his works as widely known on the Continent as in England. More importance may be attached to the rise, on the Continent, of a lighter form of opera, entitled “Opera Buffa,” in contradistinction to which opera proper received the title of “Opera Seria.” This delightful type had its rise in the intermezzo played between the acts of a dramatic piece, and only gradually obtained a separate existence: from the early attempts of Pergolesi and others there sprung an entirely new class of work, which had great influence on the history of opera generally.

Another step towards the now universally known form of opera was made when Logroscino invented the Concerted Finale, bringing several of his characters on to the stage at the same time, and giving them a simultaneous share in the music.

Let us notice that all these improvements effected in the music gradually led composers away from the true object of its use in opera, namely, that of enhancing the general effect produced; the music began to be looked upon as so important and so interesting on its own account that all dramatic considerations were allowed to lapse. Meanwhile the [Pg 13] personalities of the singers, as opposed to that of the characters they were personating, and their vocal abilities were thrust forward to the exclusion of almost all else.

This brought about an entire change of method, the dramatic and far-seeing composer Gluck remodelling opera entirely, and endeavouring to bring it, with the added resources made possible by the improvements in musical technique, into line with the consistent ideas of the Florentine amateurs, who endeavoured to reproduce opera on the model of the ancient Greeks.

Gluck’s reforms had a very wide influence upon the history of opera, which will be more fully dwelt upon in another place; an influence that may be traced in the magnificent efforts of the group of German masters that followed in the general lines laid down by him in their adherence to dramatic truth and fitness. Moreover, these composers, the greatest that the world has ever known, were developing the resources of music of all kinds, and their achievements in the field of composition generally were reflected in their writings for the stage. Consequently, we find in the operas of Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, and Schubert an advance in musical technique corresponding with the rapid strides which the art of music as a whole was then making. [Pg 14]

And again, their varied and diverse temperaments led them into widely different directions in their search for libretti, a point in which they were followed by Spohr, Marschner, Cherubini, Spontini, and others. The whole range of the field of opera was widening out, and the subjects selected for treatment were no longer solely classical or cast into classic mould, but included the romantic, the chivalrous, the supernatural, the plebeian, and other types of plot and character; these wide differences were of course reflected in the music.

Another point to be noticed about this period of opera is that the orchestra employed began to settle down into definite shape, the constituent instruments being those which form what we now call the classical orchestra. These instruments are such as are to be found (with one or two exceptions) in the orchestra of to-day, and such operas therefore admit of reproduction at the present time, because, although other instruments have been added to those which form the ordinary classical orchestra, no radical changes in methods of scoring have taken place since the time of Mozart, Beethoven, and Weber.

Opera had now become so many-sided an art form that it will be impossible in this brief resumé of its history to follow it [Pg 15] through all its varieties; the principal of these were the “Opera Comique” of the French, the Ballad Opera of the English, and the melodic and tuneful form of Italian opera, which claims Rossini as its shining light, and which, by its other sons, Donizetti and Bellini, attracted and riveted public attention in Europe for so long.

In the Italian form of opera, the aggressive and encroaching qualities of the prime donne threw certain portions of the music (i.e., their own arias and songs) into such prominence as to dwarf all else. Abuses were again to the fore; the solo singers, male as well as female, made the opera; plot, action, suitability, dramatic fitness—all mattered little so long as there were plenty of flourishes, vocal cadenzas, and roulades.

As in the days of Gluck, a strong man arose to revolutionize the whole trend of things, to turn the music back into its proper channel, to stop its overwhelmingly preponderant importance, and to restore harmony among the arts employed for the proper rendering of musical drama. This man was Wagner, beyond whose achievements opera has as yet moved no step. His methods of orchestration, his additions to the ordinary orchestra, his devices of guiding themes, and of the continual [Pg 16] employment of song-like (although unrhythmic) melody, known as Melos, constitute so many new features in the history of opera.

Modern opera, since his time, has presented us with nothing sufficiently fresh to justify for itself the claim to have had any radical influence in operatic development. The resources of the technique of the art, the increased freedom with which remote discords and far-fetched modulations are attacked, the greater facility exhibited by composers in welding various themes together, and in their use of the orchestra, are only a following of the principles and practices of Wagner. Since his mighty operas were produced there is no epoch-making event to chronicle.

Thus, side by side with the development and progress of the composition and practice of music, opera has developed and progressed, from the days of the simple monodic school, to the complex polyphony of the twentieth century. This has been briefly, and without detail, demonstrated above; and we now turn to a more analytical examination of the various phases of opera. Before doing this, however, it will be as well to examine a little more deeply into the causes of the somewhat frequent checks in its history, which we have cursorily mentioned, and of the reforms and uprootings of the abuses which have constantly [Pg 17] hindered its growth: a brief enquiry into those abuses will help us more clearly to understand what opera really should be, and also how much is due to those stalwart heroes of opera who have defied the whole of the civilized world in their efforts to establish, or to re-establish, it upon a proper basis.

Reforms, and the reasons thereof—Monteverde’s influence—Musical innovations—The stage discards music of the ecclesiastical order—The beauty of Scarlatti’s arias—Their weakness—Gluck—Gluck’s explanation of his reforms—Triumph of his methods—Another retrogression—Rossini—Wagner—The leit-motif—Influence on subsequent composers—Will further reforms become necessary, and what shape will they take?

The word reformer is here used in its original sense, for each of the composers named in the heading to this chapter had very considerable influence in the reconstitution and re-casting of the structure of opera in his day.

These were the men who, perhaps more than all others, were not content to leave opera in the groove in which they found it: for at the respective periods in which they lived opera had drifted into grooves, and it was the influence of these composers that arrested its progress [Pg 19] in the various wrong directions in which they found it drifting; they set themselves first of all to stem the currents that were carrying opera astray, and then constructed new works as examples of what could and should be done.

Hence we call them the reformers, and may now examine into the achievements of each of them in turn, noticing the condition of things that prevailed when they first entered the field, their influence upon it, and the result of their work.

First of all, Monteverde. So many innovations are connected with his name, that he would appear to have been a reformer of music in general; it is not certain, however, that all that history credits him with is really his due. But this is certain, that opera before his time was a very different thing to opera subsequent to that period.

The efforts of the early Florentine amateurs, the Palazzo Bardi enthusiasts, of whom more anon, had been towards the production of opera on the lines of the ancient Greek play. This was opera as Monteverde found it. He, original thinker and worker that he was, applied the same daring innovations to his operatic music which he had employed in his compositions for the church. These consisted mainly in an utter disregard for the principles of strict counterpoint, and a free use of unprepared discords. [Pg 20]

Now these discords, harsh and ill-sounding, when performed by a number of voices without accompaniment in the church, made a very different effect in the opera-house: the effect of a solo voice, accompanied by instruments, was very different to that of a chorus; and discordant passages, which violated both the spirit and the meaning of sacred words, were quite in their place—nay, more, they frequently heightened the dramatic intensity of the situation when used in opera. So great was Monteverde’s success, so dramatic and expressive his music, that all composers since his day have followed in his footsteps, and have composed operas on the model of free and unfettered writing originated by him.

His novelties of orchestration; his use of instruments, grouped quite in the modern manner for accompanying certain characters, or for defining particular situations, have already been touched upon; and these characteristic features continue to give him a very prominent position as a reformer of early opera. By him the complexion of matters was utterly changed, and the groove of writing in the church style for the stage, prevalent until his day, was left for ever.

SCARLATTI.

A century and more later we find a new reformer in Gluck. What had happened in the meanwhile? Opera had fallen under the great and commanding influence of Alessandro Scarlatti, whose methods, if not amounting to reform, had certainly led to abuse. It has been mentioned that he invented the Da Capo Aria; this was at first a welcome feature, because it gave point and meaning to the music, more definiteness of idea, and greater unanimity of design. Compare it with what had gone before, an endlessly dreamy musical recitation without form, without symmetry or rhythm, without set melody; the only attributes of the older style were its dramatic intensity and truth. And then Scarlatti appeared upon the scene; invented beautiful melodies, and cast them into regular mould, so that an audience knew that it only had to wait while a second part was gone through, to hear again a first part that had perhaps given much pleasure: it was a kind of encore, granted without trouble or uncertainty. We can imagine the melody-loving Italians of the day welcoming this beautiful and artistic innovation.

But the beauty and charm of the idea compassed its own ruin; for, being but a formal procedure, it did not equally suit every situation; indeed, it may readily be understood that there must have been very many occasions when it was little short of absurd, for stage purposes, [Pg 22] to go twice through the same emotional aspects and crises. In the operas, and in many of the oratorios of our own master, Handel, we may hear, and perhaps it may be confessed, be wearied by this inevitable repetition; for the sense of appreciation in music is readier than it used to be, and the more truthfully dramatic music of later generations tends to render almost intolerable a long, unchanged recapitulation of something already heard.

But apart from its dramatic unfitness, the real mischief of the Da Capo Aria lay in the fact that it attracted too much attention from the plot. Each of the principal singers in the caste demanded that he or she should have at least one example to sing, whether it suited the exigencies of the situation or no. The audience went to the opera house, not to hear an opera performed, but rather to delight in a series of bravura airs, and exercises in vocal agility, performed by popular singers. The real origin of opera was lost sight of, dramatic considerations were practically ignored, and the performance became of a lyrical, rather than of a dramatic, nature.

Now Gluck, curiously enough, had written many operas on this plan before it occurred to him to try to reform it; but his artistic nature at last revolted against the absurdities of works of this type, [Pg 23] successful though he had been in the production of such. After much thought and labour he set himself the task of remodelling the music, in a manner which can best be explained by quoting his own words, written in the prefix to the score of Alceste:—

“When I undertook to set the opera of Alceste to music, I resolved to avoid all those abuses which had crept into Italian opera through the mistaken vanity of singers and the unwise compliance of composers, and which had rendered it wearisome and ridiculous, instead of being, as it once was, the grandest and most imposing stage of modern times. I endeavoured to reduce music to its proper function, that of seconding poetry, by enforcing the expression of the sentiment, and the interest of the situations, without interrupting the action, or weakening it by superfluous ornament.... I have been very careful never to interrupt a singer in the heat of a dialogue, not to stop him in the middle of a piece, either for the purpose of displaying the flexibility of his voice on some favourable vowel, or that the orchestra might give him time to take breath before a long sustained note.... My object has been to put an end to abuses against which good taste and good sense have long protested in vain.... There was no rule which I did not consider myself bound to sacrifice for the sake of effect.” [Pg 24]

From these quotations we may form some idea both of the serious errors that had crept into opera and of the thorough nature of the reforms which Gluck contemplated. He had many, and severe, battles to fight before he gained public opinion to his side; but eventually he brought the artistic world round to his point of view, with the result that a complete change of method was again adopted by composers: the progress of opera, which had drifted into a wrong channel, was again headed in the right direction by a masterly hand, and for some time a more real and genuine school of opera held the boards.

But history repeats itself. Years passed away and operas were written both good and bad: Mozart, with his beautiful and delicate pen; Beethoven, with his imperishable picture of the faithful wife; Weber, the composer par excellence of Romantic opera; Spohr, and others all left their influences—and in the main thoroughly artistic and beautiful ones—upon music drama. To this chain of great classics there succeeded, however, a group of lesser luminaries whose tendencies were less truthfully artistic, whose leanings were popular rather than æsthetic, and whose influence was to a great extent mischievous. [Pg 25]

Most grievous of such offenders was Rossini, whose gifts of ready and spontaneous melody led him sadly astray. His knowledge of effect was wonderful, but his methods were of the clap-trap order, and although there are admirable points in his work, its appeal was made to popular taste rather than to the musician, and popular taste is a fickle thing. For a while, Rossini, with his sensuous melodies, his whirling crescendi, his tricky orchestration, carried Europe with him—into wrong paths; for the taste for such things is not a healthy one, nor can the appetite always be satisfied by a glut of sweetmeats.

Besides Rossini there was, as always, a host of imitators who follow their hero at more or less respectful distances, producing works which were pleasant enough but had little or none of the material that makes for endurance, even though the whims, fancies, and tastes of some of our prime donne are responsible for their production, now and again, even in the twentieth century.

Opera, indeed, during all this period was again straying from the right lines: again the singers, with their executive abilities, were distracting attention from the equally important dramatic meaning of the works performed. Again the aria and duet were usurping the place of [Pg 26] music which should have been defining the stage situation, and conveying to the ear of the auditor a tone-picture to match the scenic representation, and to help to carry on the action of the piece, which, indeed, during these vocal performances suffered much from stagnation.

It needed a strong hand to stem the tide on this occasion, and a strong hand was available in the person of Richard Wagner, whose efforts have revolutionized opera to so great an extent that it is unlikely that any great work for the stage will ever be conceived in the future which will not show traces of his influence. For he took no half-measures, but went to the root of the matter, and that in so thorough a way that he really invented an utterly new phase of expression. Until his employment of the kind of music which we call Melos (a continuous stream of melody without definite rhythm, tune, or cadence) music in general, and more especially operatic music, had always, from the time of the early composers of the Monodic School, paid some little regard to form and shape. But Wagner, whose great idea it was that in the rendering of opera the arts of Music, Action, Poetry, and Scenery should stand on an equal footing, was unable to allow attention to be devoted to the music in the very special way in which it was drawn when set forms of song or air were admitted. It overturned the balance which he deemed so desirable, and threw into prominence one art at the expense of the others.

WAGNER.

Consequently, with wondrous energy, skill, and in the face of the usual relentless opposition, he gradually worked his way to the construction of what was, until his time, an absolutely unknown form of dramatic accompaniment. In so far as it was continuous, and expressive of the stage situation, it resembled the music of the Italian composers who preceded Scarlatti. But the great and original innovation of Wagner was his use of melody (a feature non-existent in the works of the Monodic writers); not melody of the stereotyped nature which we designate as tune, nor even the rhythmic, square-cut, and often beautifully appropriate melody of a Mozart or a Beethoven. Wagner’s melodies were so constructed that they had, generally speaking, definite signification: every subject (or leit-motif, as it was called) was intended to suggest to the mind of the hearer some definite idea connected with something occurring upon, or suggested by the stage. Not that the entrance of a certain character was always accompanied by certain music; rather, a deeper psychological problem was offered, the [Pg 28] words sung calling up definite ideas, or such suggestions being left to the music alone on occasion.

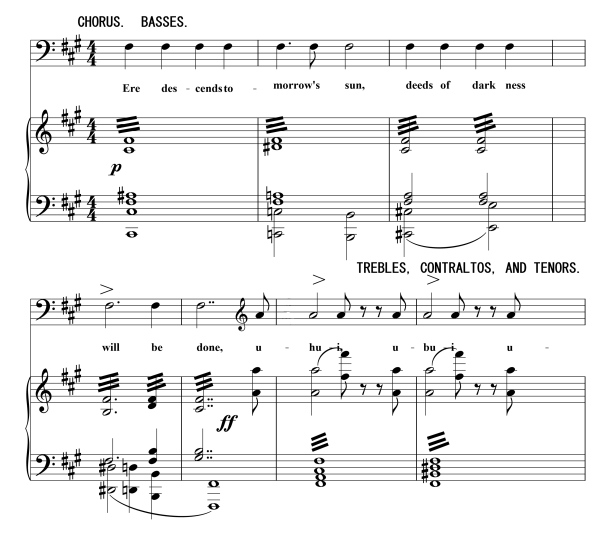

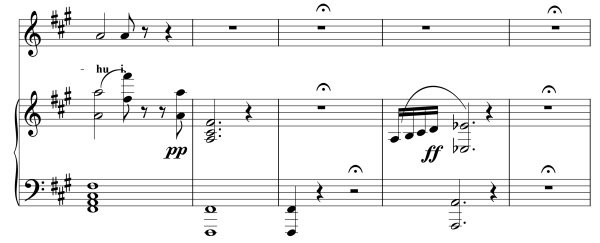

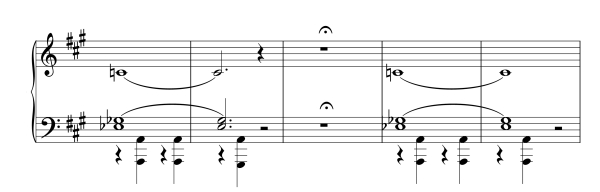

And for this type of theme Wagner chose either certain definite passages or fragments of melody, such as the opening phrase of “Parsifal”—

Melodic Leit-motif. (Wagner’s “Parsifal.”)

or certain chord progressions, such as the following:—

Harmonic Leit-Motif. (Grail Theme, “Lohengrin.”)

[Pg 29] or sometimes characteristic methods of orchestration. Moreover, since the stage action or words would very often describe or suggest many ideas at the same time, these themes would be often superimposed; with the result that the music of Wagner’s operas—at any rate the later ones—is not so much a stream of melody as a flow of many combined melodies, working together in contrapuntal richness and fertility into a harmonious whole, which can be listened to either casually (in which case it may or may not please the auditor) or after considerable study, when it will undoubtedly awake interest and admiration.

Now, between this kind of opera and that of the Rossini school it is very evident that a very vast amount of difference exists. Whereas in the latter the hearer had his ear delighted and tickled, without any trouble to himself, to his immediate satisfaction, the Wagner operas demand careful attention, study, and oft-rehearing for intelligent appreciation.

The lazy, pleasure-loving portion of mankind was immediately up in arms against such startling methods as these, and even to-day, although the Wagner-cult is a very considerable one, it is to be doubted whether the real tastes of the majority of operatic listeners are not rather for something demanding less careful and close attention. Whether this be [Pg 30] so or no, the point remains that Wagner’s innovations, when once understood and grasped, were seen to be so dramatically true and fitting that all composers of operas, since his works became widely known, have come under his influence, and have in large measure framed their dramatic music on the lines laid down by him.

Here, then, was another revolution, and an important one. Formal melody still exists on the stage, but the continuous inter-connecting links of melos are derived from Wagner, while the wondrous harmonies and chord combinations which he was the first to introduce into the realm of opera, have been so many additions to the material which the modern composer has for manipulation.

Since Wagner there have been no reformers; we do not yet see in what direction reform is to come. If we are to rely on history, which certainly seems to repeat itself with regard to opera, we are probably slowly trending in some wrong direction or other. What that wrong direction is we shall only know when some mighty master mind has turned us out of it. It may be that the Wagner operas, which seem at the present time to be the height of dramatic perfection, may yet contain many serious flaws, either in workmanship or in method; this much is certain, that no imitator of Wagner has achieved permanent success: the [Pg 31] Colossus stands alone, and none can vie with him on his own ground.

But opera must go on: if the Wagner reforms cannot be successfully adopted and used by others, operas will be written (as they are being written) on other lines. Some of these new works will be good and some bad, but the present seems to be a period of interregnum such as succeeded the times of Monteverde and of Gluck. We are experiencing a spell of more or less unimportant operatic production which will, in all probability, go on slowly in some wrong direction until the brain of some clear-sighted and gifted genius has discovered that we are all astray, and will alter the whole course of things. Until his advent we have no name to add to our list of reformers of opera.

Early commencement of opera—The Bardi enthusiasts—What they achieved—Peri and Caccini—A logical commencement—Its imperfections.

It is a curious and interesting fact that the birth of opera should be due more or less to accident, and should owe its origin to a group of amateurs: but so it is, and to the blind gropings in the dark after a something (they knew not what) of a small circle of polished scholars, we owe the form of opera as we have it to-day.

It is impossible to trace back to the earliest times the addition of music to a stage play; from the constant references to the use of the art made by the Greek poets, we know that it was a handmaid to the drama from very early times. In the Middle Ages, too, there is plenty of [Pg 33] evidence to show that, at certain stated intervals in the course of the drama, music was introduced; but such music as this was always written in the church style of the period, and had no significance of its own.

It was the annoying and incongruous presentation of polyphonic music (written in strict contrapuntal style, and in the church manner) with the performance of dramas, in which such music was utterly out of place, that led the band of amateurs mentioned above to search for a more suitable means of clothing the dramatic ideas and stage situations.

This band of dilletanti is generally known by the name of the “Palazzo Bardi” coterie, from the fact that their chief representative was a certain Count Bardi, and that their meetings were usually held at his palace in Florence. This city was, at the period of which we write (the last part of the sixteenth century), highly interested in the masterpieces of literary antiquity, more especially in the magnificent dramas of the older Greek poets. Although the Florentines knew that these tragedies had some form of musical accompaniment, they were quite in the dark as to what that music was; they felt, however, that the one and only prevalent kind of music of their day—i.e., sacred [Pg 34] music, was by no means adequate for the expression of the ideas to be represented. The Bardi amateurs therefore turned the steps of their native musicians towards other paths, and induced them to write music of a kind which they believed to be dramatically fit and suitable. That this music was a failure does not matter in the least, for although it was unable to give any genuine idea of what these enthusiasts sought—namely, a reproduction of Greek tragedy consistent with its original form—it invented a new medium and method of expression, of which composers soon availed themselves in setting to music the dramatic productions of the day. The first of these early composers to achieve success in this field was Peri, who produced in 1594 (or 1597) Daphne, and a few years later, in 1600, Euridice. Daphne was semi-privately performed, but Euridice was put before the world, and achieved such success that its method and style of composition were soon taken as models for stage music. Hence the date 1600 is assigned as that of the birth of real opera; the same year seeing the production of the first real oratorio, as we now understand the term. We quote the whole of the short prologue to the earliest known opera: [Pg 35]

Prologue to “Euridice.” (Peri, A.D. 1600.)

[Pg 36] while for an example of early operatic dance-music the final “Ritornello” from the same opera may serve as illustration.

Final Ritornello in Peri’s “Euridice.”

Questo Ritornello va riplicato più volte, e ballato da due Soli del Coro.

Peri led the way; others followed. In a short decade the North of Italy produced a whole school of writers who had grafted their ideas on those of the composer of Euridice, chief among them being Caccini, who won great fame in the new style. But the chief merit must be accorded to Peri, for it was to him that we owe the invention of the dramatic recitative; that is to say, instead of coupling the dialogue to music that might have been designed for the church, as his predecessors had been content to do, he endeavoured in his operas to allow the singing voice to depict the ideas expressed by inflections such as would be made by the speaking voice under similar circumstances. As he himself tells us in his preface to Euridice, he watched the various modifications in sound made by the speaker in ordinary conversational dialogue, and sought to reproduce these in music: “Soft, gentle speech by half-spoken, half-sung notes on an instrumental bass; more emotional feelings by melody of more disjunct character, and at a quicker rate,” etc.

Thus was opera, in our modern meaning of the term, begun, and this, too, on a proper, logical, æsthetic basis. It was in 1600 a new form, an untried and questionable innovation; but it contained the elements [Pg 38] of strength and endurance, and by rapid steps grew and developed, until within a few short years all other methods of accompanying stage plays by music were obsolete, and the new “Monodic” style held unquestioned sway.

Crude it certainly was, for modern tonality, as we understand it, was still undeveloped; harsh and ugly much of its music must have been, for melody was unknown, time was practically non-existent, and of form there was none. And yet, in so far as it sought in its music to faithfully reproduce the dramatic situation, such work was more truly of the essence of opera than many another of more recent date and of greater success. Unlike the polyphonic choral music of its date, it will not bear performance in our own day, yet for it must be claimed truth, strength, and clearness of aim; as pioneer work it has been invaluable.

Monteverde—Scarlatti—Cambert—Lully—Keiser—Purcell—Handel in London—Handel’s rival, Buononcini—Handel’s operas now obsolete by reason of their lack of dramatic truth.

Opera in Italy, after its initial stages, as represented by the works of Peri and Caccini, fell under the commanding sway of Monteverde, of whose influence we have already said much in the chapter upon the “Reformers of Opera.” An example of his melodious, although, of course, somewhat crude style, may be seen in the “Moresca” which we append:— [Pg 40]

Fragment of a “Moresca” (Dance) from Monteverde’s “Orfeo” (1609).]

[Pg 41] Monteverde was followed by his pupil Cavalli, who worked in Venice, and who improved the recitative; in his operas, male sopranos (Castrati) were first employed on the stage, a practice in vogue for many years subsequently. Cavalli also foreshadowed the aria, or set melody, soon to become so prominent a feature of Italian opera. Among other prominent composers of this period are Cesti and Legrenzi, Caldara and Vivaldi.

These men, however, stand completely overshadowed by that Colossus of early opera, Alessandro Scarlatti. Naples was the scene of his activity, and here he wrote, amongst countless other compositions, over one hundred operas, most of which made their mark. In Scarlatti we have the turning-point between antiquity and modernity in stage music. Of course his operas sound old-fashioned to us, but it would be quite possible to listen to them, whereas those of a former date could only have antiquarian interest if produced now. His great genius for melody caused him to modify very considerably the stiff, though dramatically correct, recitative of earlier composers, and to substitute beautiful, and sometimes inappropriate, airs in its place. [Pg 42]

In this dangerous method of exalting the music at the expense of the other arts employed in music drama he was followed by almost all composers for very many years—until, in fact, the recognition by Gluck of the falseness of the situation. Opera writers there were by the hundred: the names of most of these are now forgotten—many remembered; Rossi, Caldara, Lotti, Buononcini, all had their successes, and contributed in various degrees to the development of early Italian opera.

But before this, Opera had found its way to France; the world-renowned Euridice had been performed in Paris as early as 1647, and its influence was quickly felt. Masques and ballets had been staged before this time, but Robert Cambert was the first French writer to produce opera. At first successful, Cambert was ousted from his deservedly high position as the founder of French opera by the unscrupulous and brilliant Lully.

For Lully “came, saw, and conquered.” Although an Italian,[1] his name is one of the most prominent in the history of opera in France. Coming from Florence to Paris at an early age, he quickly saw his way to improving on the popular operas of Cambert, and his inventive and fertile talent soon put the older writer into the background. Lully’s great gift lay less in aptitude for the conception of melody, or even in his skill with the orchestra, than in the powers he possessed of writing truly dramatic and suitably expressive recitative. Moreover, he employed his chorus as an integral factor in the situation, not as a mere collection of puppets encumbering the stage; he is credited, too, with the invention of the “French” overture, a form in which an introductory slow movement is followed by another in quick fugal style, with a third short dance movement to conclude. Like Scarlatti in Italy, Lully in France towers high above all opera composers of that period, and his mark upon French Grand Opera exists till this day.

LULLY

Germany at the same period can boast of no name of like importance, but operatic development was taking place in this country also, the chief agent in its progress here being Keiser, who produced a great number of operas in Hamburg. Although not the first to write such works in Germany, he is important as being an early factor in the popularization of opera during the forty years in which he laboured in this direction: he had also many followers, among whom must be named Handel, who wrote a few operas for Hamburg at an early period of his career. German opera at this time, however, gave but little promise of the grand future before it: the operas of Keiser and Hasse contain but few indications of [Pg 44] the glories of a school of composers that includes Mozart, Beethoven, and Weber.

And what was England doing at this period? One genius of the highest rank, some would say the greatest child of music that England has ever produced, was at work in the form of Henry Purcell, whose too short life was in part occupied by the composition of opera. Spontaneity of melody, freshness and boldness of thought, and rare dramatic conception are the chief characteristics of the works of our early English master. Many of these are operas by courtesy only, for in only one of them, Dido and Æneas, is the music continuous throughout; this, however, may claim for itself the title of the first English opera. Before this time (about 1675) masques and plays had employed music incidentally, but Dido is the earliest known instance of its continuous use. Purcell did not follow up his early operatic success, most of the other stage works, such as King Arthur, containing spoken dialogue. It is unfortunate for England and her musical sons that the dominating personality of Handel so soon overshadowed all other musical life in this country: the wholly sound and æsthetically true national influence of Purcell would undoubtedly have been large, and it is not too much to say that an early school of genuine English [Pg 45] opera might have flourished, had it not been that the great Saxon composer was, within a few years of Purcell’s death, turning his attention to the production of opera in London.

For although Handel produced operas in Germany, in Italy, and in England, it was in London that the very large majority of his pieces first saw the light, and that he achieved the greatest success. Between the date of the first performance of Rinaldo at the Haymarket, February 24th, 1711, and that of his last opera, Deidamia in 1741, Handel composed no less than forty-two grand operas. With indomitable energy, and in face of very frequent misfortune, he poured forth these works, many of which contain powerful music. Undeterred by failure, he took one theatre after another in London, sometimes making much money, at other times becoming bankrupt. The final stage in Handel’s operatic career was brought about by a lengthy and expensive rivalry between him and a clever Italian composer, Buononcini, who had been brought to England by an influential body of nobles and politicians whom the fiery Handel, and his supporters, had offended. The dispute became more than a musical one, and developed social and political sides: an amusing epigram by one John Byrom neatly sums up the situation:—

The sentiment of the two last lines was probably voiced by many, especially as both composers were men of great talent and capable of producing excellent work. In the end, the genius of Handel triumphed, but at the expense of both his pocket and his health; bankruptcy and paralysis came upon him, and he in future turned his attention to the more lucrative and less expensive art form, Oratorio.

That we have been the gainers thereby is undoubted, for whereas many of his oratorios are constantly performed, and are of commanding interest, few would care to sit through a performance of any of his operas, or indeed those of any of the composers mentioned in this chapter. It is not so much that the music is expressed in the idiom of a bygone era, for the style of Handel’s oratorio and opera music is, especially in the arias, very similar; and we are frequently able to listen with pleasure to old works, written for the clavier and for stringed [Pg 47] instruments by the Continental contemporaries of the men of this period. It is rather that the dramatic situation is so absurdly poor, that the stereotyped method of procedure in the distribution of the airs, the concessions to the solo singers and the character of the music given to them, and the stiff, unnatural use of the chorus in these operas, combine to make their presentation to-day a matter of artistic impossibility.

Gluck and his masterpieces—Mozart—Beethoven—Weber and romantic opera—Der Freischütz—Other operas—Schubert—Opera writing a distinct form of composition—The small influence of the really great composers upon opera.

The methods of Christoph Willibald Gluck, and his influence upon all that came after him, have already been touched upon. Unlike the operas of Monteverde, the works of the later reformer still hold the boards, and therefore a little consideration to these may now be given, seeing that they influenced the composers of all schools and of every nationality.

We may safely ignore the many works written on old methods and produced during the first forty years of the composer’s life; they are practically as obsolete as those of Monteverde. But those written under [Pg 49] the strong convictions forced upon him by comparative failure in England are of great importance, and are interesting, not only for the models they set to others, but also for the beauty and worth of the musical ideas which they contain.

Those that have the greatest claim to notice have the following titles:—

Of these works, the famous story of Orpheus and Euridice has perhaps the most dramatically beautiful musical setting, and is more often heard than are the other operas; be it borne in mind, however, that even in this masterpiece there is much that sounds antique both in method and in form; this is of necessity the case, when one considers the date at which Gluck wrote and the comparatively backward state of the art of music in the mid-eighteenth century. [Pg 50]

Gluck’s type of melody may be discerned from the following quotation:—

The commencement of the famous Aria, “Che faro,” from Gluck’s “Orfeo.”

Gluck, even in his later works, never reached the height of musical technique that was attained to by a young and glorious composer who was his contemporary for thirty years—almost the whole of his short life. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart had other models to guide him, for the works of Grétry, Piccini, Sacchini, Benda, Cimarosa, and others were known to him, and in his scores we find a summing up of, and an improvement upon, all operatic music previously penned.

Mozart handles the orchestra in a more modern and a vastly more masterly way than any of his predecessors; his operas, too, deal with such a variety of subject that they show infinitely more resource and diversity of treatment than those of Gluck, which were all written on [Pg 52] the “grand” model. We feel that we have to do with men and women, creatures of flesh and blood, and not with far-away, shadowy classic shapes, whose appeals to our sympathies must naturally be less vivid. His melodies, too, of round, full outline, possess a richness of expression and a warmth that is not always discernible in the older master; and in addition we have vivacity, charm, and piquancy in the lighter scenes which had no place in the products of the more severe school. Two examples of Mozart will serve to illustrate his style. The first shows him in a lyrical mood,

A fragment of a Mozart “Canzone,” “Voi Che Sapete” (The Marriage of Figaro).

[Pg 53] while the second gives us the composer in more dramatic guise.

The famous passage from Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” when the Commandant appears.

[Pg 54] Mozart’s most successful operas are:—

These, the most popular of which are The Marriage of Figaro and Don Juan, are written, for the most part, in the then prevalent Italian style. German opera, as a distinct national product, was not yet born, and although Mozart’s Magic Flute was a step in this direction, it is his Italian works that raise his name to so high a pinnacle in the temple of operatic fame. The bright and sparkling [Pg 55] Figaro is to be heard in every country and in many languages, while its more sombre companion, Don Juan, with its highly dramatic and noble music, is even more widely performed.

Beethoven, with his solitary opera, Fidelio, produced in Vienna, 1805, is a landmark. Although Italian in form to a great extent, this work shows tendencies towards that school of romantic thought which was so soon to become the characteristic feature of the best period of German opera; the music, carefully wrought and intrinsically beautiful, makes large appeal to the emotions; although in reality only a “Singspiel,” there being spoken dialogue, it is generally classed with grand opera, its music being so noble and dignified. An example of the greater modernity of Beethoven’s style may be seen in the subjoined passage.

Adagio opening of Beethoven’s “Leonora,” Overture No. 3,

introducing the theme of Florestan’s Air in Act III.

Romantic opera (i.e., opera in which the influence of the romance school of literature, as opposed to the classic, is felt) owes its prominence in the first place to Carl Maria von Weber. The music of such operas differs from that of the more classical models in its greater richness of harmony, its more remote and poignant use of discords, its sudden and unexpected turns of modulation, and its more picturesque orchestration. Although there are many suggestions of romantic opera before his day, it is to Weber that the credit of the foundation of this school of composition is, as a rule, usually ascribed. With his wonderfully beautiful work, Der Freischütz, he [Pg 57] led the way into a vast, and as yet comparatively unexplored field; other composers were ready enough to follow him, but his leadership is unquestionable.

The opera Der Freischütz lent itself particularly to the new mode of treatment: its story deals with the weird and the supernatural, and thus seems to demand a form of treatment distinct and different from that accorded to the calm and stately libretti of the older schools of opera. In his setting of this story, Weber made slight use of the conventional Italian methods; it is a German opera, pure and simple, with constant reference to the Volkslieder, and a noticeable absence of the stereotyped conventionalities of Aria and Ensemble.

Here is a short illustration from the famous “Incantation Scene”:—

Fragment from the Incantation Scene of “Der Freischütz.”

(The clock strikes twelve in the distance.)

Caspar (speaking

through the music):

“Zamiel, by the wizard’s skill appear! Zamiel, hear me, hear!”

Der Freischütz was produced in Berlin in 1821. Like so many other of the finer old operas, it is a “Singspiel,” but for all that it still holds the boards, although modern taste in serious opera now prefers the continuous use of one means of expression—namely, music. It is almost the only opera of Weber’s that is ever heard, for Euryanthe, produced in Vienna in 1823, and Oberon, produced in London in 1826, in spite of their beautiful music, are unfortunately so poor from the dramatic point of view as to be almost intolerable, while the earlier operas previous to Der Freischütz do not show the composer at his best.

In Weber, whose one great work has had an untold influence upon operatic composers, we meet the last of the great masters (from an operatic point of view) until Wagner. Schubert, Schumann, and Mendelssohn were all so versatile that they achieved some success in opera; but it must be confessed that for any abiding result their work [Pg 60] has had, they might not have composed such works at all. Lesser stars in the musical firmament, such as Spontini, Marschner, and Meyerbeer, have had greater and wider reaching influence in this particular branch of musical art.

This is partly owing to the fact that these three mighty men of music were of a non-dramatic nature: Schubert more often turned to the stage than did Schumann or Mendelssohn, and his beautiful melodies and skilled knowledge of effect helped on his operas towards success in their day; but even his most popular examples, Fierabras and Alfonso and Estrella, very rarely obtained a hearing. Mendelssohn’s early works, The Wedding of Camacho and his fragment of Lorelei, are also comparatively unimportant, while Schumann’s Genoveva cannot be classed among the list of works in the ordinary repertoire.

It is curious and interesting to notice how small a share those who have reached the topmost pinnacle in the musical temple have had in the development of opera; while the influence of the great classical and romantic composers has been exerted with immense sway over almost every other form of the art, and while that influence has elevated and exalted such art forms to dignified and poetic heights, they have, with [Pg 61] the single exception of Mozart, left opera almost unaffected.

The heroes of opera, Gluck and Weber, were of far less importance as all-round composers than many of the masters whose operatic efforts they completely eclipse. Whereas without Gluck and Weber it would be difficult to conceive the position of opera to-day, we must admit that they have had little influence over other branches of composition.

On the other hand, the names of those most honoured in the art of composition appear seldom or never upon the operatic play-bill. The great contrapuntist, Bach, wrote no music for the stage; Haydn, the so-called “father” of the sonata, the string quartet, and the symphony, only composed a number of unimportant light operas; Beethoven, the perfecter of form and design, one solitary, though notable, example; Schubert, the unrivalled composer of songs, a few early works; Mendelssohn, the calm and classic writer of the oratorio, and of the beautiful orchestral overtures, a few boyish pieces; Schumann, the daring inventor of so many harmonic and rhythmic designs, and the composer of many a masterpiece of pianoforte and chamber music, again a [Pg 62] solitary and little known specimen. Brahms, the great apostle of absolute music, and of the classical school, followed Bach in leaving the stage severely alone.

Mozart stands out as the one great composer who rose to the highest point of eminence, not only as a creator of sonata, quartet, symphony, and choral work, but also as a consistently great and successful master of opera. All honour to the great versatility of his immeasurable genius!

(a) THE ITALIAN SCHOOL (CIMAROSA TO VERDI).

The Italian school—Opera Buffa—The Neapolitan school—Piccini—A notable contest—Cimarosa—Rossini: his Barber of Seville—Recitative and its significance—William Tell—Bellini and Donizetti—Verdi: his early and later operas.

Italy was the birthplace of modern opera, and for generations the language of opera was Italian, irrespective of the nationality of the composer. Thus a large number of the operatic works of Gluck and of Mozart, both of whom rank as German masters, were to libretti in Italian. On the contrary, many Italian-born musicians, such as Cherubini and Spontini, devoted their best efforts to Grand Opera in France. When speaking of the Italian school, therefore, it must be understood that the language of the libretto and the class of opera are taken into account, rather than the nationality of the composer. [Pg 64]

Side by side with Grand Opera, as typified by Gluck, there grew up a lighter and less serious form of musical play known as “Opera Buffa.” At first designed as an interlude or intermezzo between the acts of a serious drama, this new and bright art form was so fascinating as to quickly justify for itself a separate existence. It was mostly harmonious in character, and the music was, appropriately, of slighter texture. It flourished most luxuriantly in Naples, from which fact the composers of these charming little operas are generally classed as the “Neapolitan school.”

Logroscino (born about 1700), who invented the connected series of separate movements known as the Concerted Finale, and Pergolesi (1710-36), who wrote a famous example of this kind of opera under the title La Serva Padrona, are two notable members of this little band of composers. In addition to these may be named Jomelli, Sacchini, Galuppi, Paisiello, and Piccini, the last-named being specially famous through his contest with Gluck, a musical duel yet more notorious than that between Handel and Buononcini already mentioned. For Piccini, a man of great talent though not of genius, was brought to Paris in 1776 and pitted against the reformer Gluck, whose revolutionary methods of [Pg 65] procedure met with anything but favour in certain quarters. The rival composers, strongly backed by their respective supporters, fought bitterly for pre-eminence, with results only too disastrous to the poor Italian maestro, who was very unfortunately handicapped. For we read that on the night of the first production of the work, which was seriously intended to beat Gluck on his own ground (the same subject for a libretto—viz., Iphigenia in Tauride—having been chosen), his music was almost wrecked by the prima donna of the occasion, that good lady being hopelessly intoxicated; whereupon men exclaimed, “Not Iphigenia in Tauride, but Iphigenia in Champagne!” In spite of his merits, this composer of eighty operas is now hardly known, except in connection with this famous controversy.

CIMAROSA.

A more famous Neapolitan is Cimarosa, whose sparkling work, The Secret Marriage, is still played to-day. On the occasion of its first performance at Vienna in 1792, the Emperor was so delighted with it that he ordered its repetition on the same evening, thoughtfully providing the artistes with supper between the performances. Cimarosa’s other works, although charming and sometimes of great beauty, are now practically dead: his fame was soon eclipsed by that of the young and rising Mozart. [Pg 66]

With the success of Mozart and Weber in German opera, and the desertion of the Italian methods in favour of the French by Cherubini and Spontini, Italian opera lay for a while under a cloud. This was dispersed by the furore created by the operatic creations of Rossini, who, although by no means a very skilled or capable musician, had a rare knowledge both of effect and also of the kind of thing to which the general public loves to listen. Melodic gifts were his, and when one adds a certain clever and tricky use of the orchestra and an evident desire to give the singers the most vocal and effective music that he could possibly invent, we can readily understand how successful was this facile composer.

The earliest of his operas to win him fame was Tancredi, a grand opera produced in 1813. This was followed after an interval of two years by the production of one of his best known works, The Barber of Seville, an excellent example of Opera Buffa. Its overture is well known, and introduces samples of that effective device, cheap and yet wondrously convincing, known as the “Rossinian Crescendo.” This is attained, as will be seen, by the use of a simple figure of [Pg 67] melody begun very softly and continued with greater and greater degrees of power and more and more instruments. In spite of its simplicity and obviousness, its effect is an intoxicating one, and is an example of the simple and yet unfailing means by which Rossini attracted his public. [Pg 68]

Example of a Rossini “Crescendo,” from the Overture to “Il Barbiere.”

[Pg 69] The whole opera, with its brilliant bravura voice passages, its grandiose effects of double thirds, and its periods of climax, is particularly characteristic of its composer. Rossini produced a vast number of operas, both serious and comic; in the former he made a great innovation when he wrote Otello in 1816. We have already frequently mentioned that in Grand Opera the music must be always continuous; this, however, does not imply a continuous series of airs, duets, and choruses. These were divided by passages of blank verse or dialogue, which correspond to the passages of dialogue with which we in England are so familiar in the productions of Gilbert and Sullivan. [Pg 70] When these passages were spoken, as in Beethoven’s Fidelio or Weber’s Der Freischütz, the work, however tragic in subject, was not termed “Grand Opera” at all, but rather “Comic Opera” or “Singspiel.” When, however, all was sung, then the term “Grand Opera” was applied.

But a difference was given to the musical setting of such passages to that allotted to the more lyrical portions. At first, when there were no lyrics, as in the early Monteverde operas, the musical setting was of the same character throughout; after the introduction of the Aria into opera by Scarlatti, the intermediary dialogue was often set to music of a parlante (or speaking) nature, generally without time divisions or musical accent: this portion of the music was termed the Recitative.