A COLLECTION

In Verse and In Prose

ILLUSTRATED

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

CHICAGO :: AKRON, OHIO :: NEW YORK

MADE IN U. S. A.

COPYRIGHT 1914

BY

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING CO.

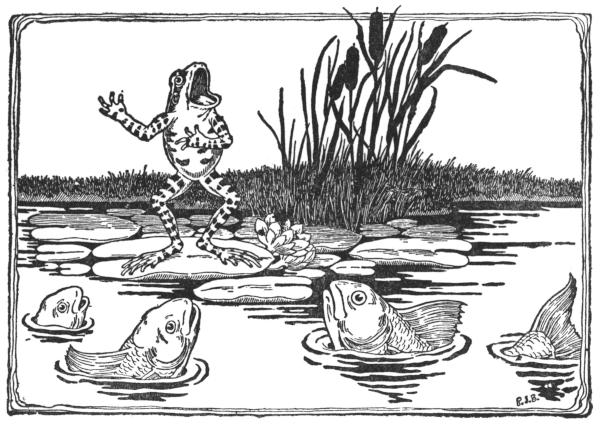

“Croak! Croak! Croak!” sang the frog one fine summer evening.

“Really,” he thought, “I have a very fine voice,” and the fishes putting their heads out of the water thought so too. But fishes have no voice at all, so perhaps that was why they thought the singing of the frog so wonderful. Then, too, he was their next-door neighbor, and the doings of next-door neighbors are sometimes thought more wonderful than the doings of persons at a distance—though at other times it may be just the other way about.

Froggie was very proud of his voice, and as he knew the fishes were proud of it too, he thought he would be sure to charm the world with his singing. So he set off across the fields and sang to the little field-mouse and the mole.

But the field-mouse thought her own shrill note far finer than Froggie’s coarse croaking, and did not pay much attention to him—in fact her attention was very much taken up with a beautiful nest she had made of grass, to keep her little ones warm and dry; while blind mole did not even put his head above the ground to hear the singing, he was so busy burrowing tunnels and making his wonderful fortress.

Froggie left them in disgust, and journeyed on till he came to a garden.

“Surely,” he thought, “in this beautiful place my singing will be welcome.”

But no one paid any attention to Froggie there; the bees were too busy gathering nectar and pollen from the flowers to make honey and bee bread, to feed the young bees at home in the hive.

The summer was going fast and they knew they had also to get in store for the winter, so they had no time to pay attention even to the finest singing; while the bumble bee was buzzing away as fast as he could to get back to his nest on some mossy bank.

The butterflies had only a little while to live; and perhaps the only thing they were thinking about, besides sipping some sweet juices from the flowers, was where to find a nice leaf on which to lay some eggs, so that when the little caterpillars were hatched they should have something to eat. The caterpillar was just spending his life eating as much as he could, so that he could turn into a beautiful moth by and by, and fly about in the evening.

The snail was going along very slowly, it is true, but as quickly as he could, only thinking of finding some safe spot where a thrush could not find him and break open his shell and eat him up. As for the spider, his one care was to catch a passing fly or daddy-long-legs and make a good meal.

Even the flowers themselves did not pay any attention to poor Froggie. Their own bright colors, they thought, were finer than any singing. Besides, they were wondering whether the sunshine would last long enough to ripen their seeds, so that they could come up again as flowers next year.

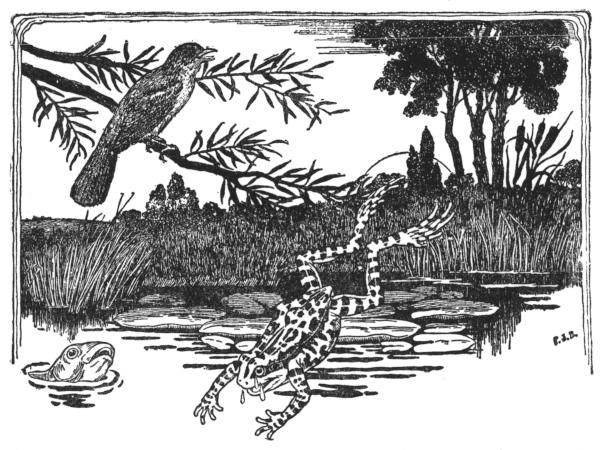

So in the evening Froggie hopped all the way back to his native pond, where he found a brown bird singing a most beautiful song. It was the nightingale.

“Really,” thought Froggie, “I am no singer after all!”

But one of the little fishes who saw his disappointment still thinks he has a wonderful voice.

The Rain Sprites Call Greetings to Me

Pip, Pop, and Pepper were three little roly-poly pups. One morning Bruno, their mother, left them fast asleep in her snug, warm kennel and went for a walk.

Presently little Maggie came tripping along all ready for fun and mischief, and when she reached the kennel she stooped down and peeped inside.

“Oh, you darlings!” she cried when she saw the puppies. “Come along with me and we’ll have some fun!”

She dragged poor Pip, Pop, and Pepper out of the kennel and put them in her apron. The puppies didn’t like it at all. They blinked their sleepy eyes and gave little frightened squeaks, and wondered wherever in the world they could be going.

“Now, I think you shall walk,” said Maggie. And she sat down, and the puppies rolled out of her apron on to the ground.

They picked themselves up, so glad to be free, and before Maggie could stop them off they ran, each a different way!

“Come back, come back!” she cried, and raced after Pip.

But Pip didn’t mean to be caught again just yet! He scampered in amongst some bushes, and dodged Maggie in and out for a long, long time, until at last he was so tired that he allowed her to pick him up.

“And now, where are the other two?” said Maggie. Oh, where indeed!

Pop ran into a chicken coop. And when Mrs. Hen came up with her fluffy babes she found a funny little furry creature fast asleep in her house.

She was very angry. She clucked, and flapped her wings, and was just beginning to peck poor Pop when Maggie ran up and pulled him out.

Then Maggie heard a terrible noise. And looking round she saw poor Pepper surrounded by Puss and her three little kits with their backs up, hissing and miaouing with all their might.

“Bow-wow-wow-wow!” Off flew Puss and her kits, and scrambled up a tree. The next moment Bruno came bounding up, and oh, wasn’t Maggie glad to give Pip, Pop, and Pepper back into their mother’s charge!

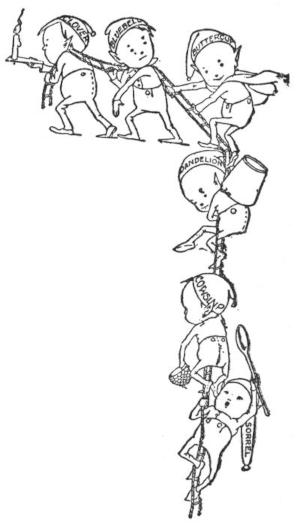

There was once a little goblin woman who had six sons. They were very ugly little boys with brown, wizened faces, and eyes as black as sloes. They had very big heads, and though they were so fat, their legs were so thin you wouldn’t believe!

Now, the little goblin woman thought the world of her six little sons, and she had given them all pretty flower names—Clover, Buttercup, Sorrel, Bluebell, Cowslip, and Dandelion.

The little goblin woman was very poor, but the way she managed was something wonderful! She and her little family lived in a hollow tree, with a little garden round it. There were three floors inside and a little string ladder connected the rooms. The first floor was a kitchen. It was ever so clean and cosy, and it was here that the family had meals, and sat in the cold winter evenings round the little twig fire, listening to the wind and rain outside.

The next floor was a bedroom, and the top floor was the drawing-room. Its walls were decorated with colored leaves, and it was here that visitors were received.

Well, one cold, rainy evening the whole family was sitting round the kitchen fire drinking broth, when the little goblin woman said, “Dandelion, it’s your turn to fetch the water to-night, dearie.”

“Yes, Mum,” said Dandelion; and taking his last drink of broth he ran to wash his acorn cup and put it away.

“You do make lovely broth, Mum,” said Clover, smacking his lips.

“Not half!” cried the other five little goblins all together.

“That’s right,” said the little goblin woman. “Good-bye, Dandelion lovie; don’t be gone all night.”

“Good-bye, Mum,” cried Dandelion, nearly hugging the little woman’s head off; and away he ran with the wooden bucket over his head.

He had not gone far through the forest when he heard a sound of crying. So he took the bucket from over his head and looked about. Then it was that he saw a great big shoe standing in a puddle, and it was from this shoe that the sound of crying came. Dandelion crept nearer, and, looking through a little hole in the heel, was just in time to see an old woman smacking a wee girl about his own size.

“Hi!” cried Dandelion, “stop that!”

In her astonishment the old woman stopped, and the little girl scuttled into the toe of the shoe.

“May I come in?” said Dandelion, and without waiting for an answer he scrambled through the hole and dropped into the shoe. The old woman looked at him for a minute very angrily, then burst into tears.

“Oh, the little wretches!” she cried; “they do lead me a life! Oh dear! Oh dear! Oh dear! I’ve got so many children I don’t know what to do!”

“How many?” asked Dandelion.

“FIVE, if you’ll believe me!” cried the little dame; “and them always getting into mischief.”

“There’s six of us,” said Dandelion.

“Oh, your poor ma!” cried the old woman with uplifted hands and upturned eyes.

“She likes it,” said Dandelion.

“Don’t tell me!” cried the old woman. “I know what children are—always disobedient. Why this very night E. and D. walked through the puddle a-purpose.”

“Who did?” asked Dandelion, thinking he had not heard aright.

“E. and D., my dear,” answered the little woman. “I calls ’em by the letters of the alphabet. It saves the trouble of thinking o’ names. I called my eldest Arabella—Aida—Alice; but when they come so quick letters was good enough.

“Now, C.,” she broke off, “back to bed at once with you or I’ll whip you again and you shan’t have any broth to-morrow.”

Dandelion turned quickly and saw five little tear-stained faces peeping at him from the toe of the shoe.

“Perhaps,” he said softly, “if you didn’t whip ’em, they’d do as they were told.”

The old dame looked at him in astonishment.

“And perhaps the broth isn’t so nice as what Mum makes,” added Dandelion. “They couldn’t cry if they had a cup of her broth.”

“Dear me!” cried the old woman; “what next!”

“You come and see my Mum,” said Dandelion, “and have a talk to her. I’ll call for you when I’ve fetched the water.”

“Well, now,” said the old dame, “it ain’t often I goes on a little visit. It’ll be a change.” And she put on her bonnet.

That night the old woman woke the children up and gave them each a kiss, which surprised them very much; but they were still more astonished when she gave them each some broth with bread.

“My dears,” she said, “you’re going to have bread in your broth every night. And I’ve got a new soup recipe in my pocket. What’s more, we’ve all been asked out to tea to-morrow, so I’m going to put your hair in curl-papers.”

“Oh, no, no!” screamed the children; “you’ll pull, and then we shall cry and you’ll beat us!”

“I ain’t going to beat you no more, my dears,” said the old woman, kissing them all again. “I’ve learnt a lesson.”

“Come in, my dear, come in!” cried Mrs. Goblin. “I’ve lit a fire in the drawing-room, so we can have a little talk while the children play in the kitchen. And now, my dear,” she added, when they were alone, “now you are here what’s to hinder you from stopping?”

The old woman was crying for joy. “But so many children!” she said presently.

“The more the merrier! We’ll all live together and be as happy as the night is short!”

And so they did.

One day, little Simon Brownie said to his brothers, Joe and Sam, “I would give the world if I could grow. I wish I was a giant instead of a Brownie.”

“Ha! Ha!” laughed Joe.

“Ha! Ha!” laughed Sam. They thought it a fine joke.

“If you want to grow so much,” said Joe, “you must eat plenty of porridge.”

Next morning at breakfast, Simon, to his mother’s surprise, asked for a second helping of porridge. (As a rule he scarcely finished his first.) For a whole week he did this, but not a tiny, wee bit did he grow.

“Porridge is no use,” said Simon to Joe and Sam, “Can’t you think of something else?”

But his brothers shook their heads. Next day however they thought of “something else.”

Simon, tired out with play, had flung himself under a toad-stool for a nap.

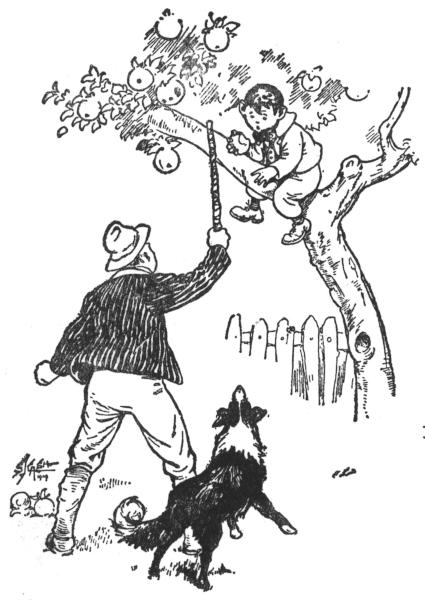

“Let’s water him,” whispered naughty Joe to Sam, “the same as mother does the flowers—that will make him grow.”

And without wasting any more words, he ran home for his watering-can. Presently Simon awoke all in a hurry, thinking that an April shower was pouring down upon him. When he found out it was Joe who was watering him with his can, he was at first quite angry.

“Don’t be cross, Simon,” laughed Joe. “I only did it to make you grow!”

And Simon who knew how to take a joke, laughed too.

Since that day he has grown, not much bigger perhaps, but certainly wiser.

“I’m going on a voyage of discovery,” said Mr. Brownie to his wife, one morning at breakfast. “You might pack me up a few sandwiches, my dear.”

Of course Mrs. Brownie, being a kind wife, said, “Yes, with pleasure.”

“Where are you going to, Daddy?” asked Bobby Brownie, who was rather a pert little fellow.

“I am going,” said his father in a very grand tone, “to discover the West Pole.”

“The West Pole!—Never heard of such a place! Where is it?” said Bobby.

“It is close to where the sun sets,” was the reply. “The exact spot is left for me to find out.”

And shortly after breakfast Mr. Brownie started forth.

He tramped a long, long distance until at last he came to a meadow near a farm-house. Here he saw—not the West Pole but a toad-stool which had sprung up in the night.

“Dear me,” said he, looking at it all round, “this seems very ancient.”

When he got on the top and was looking at it in wonder, the farmer’s geese came and had something to say to him.

“Who are you, when you’re at home?” they cried in goose language. “You think yourself a very fine fellow, no doubt!”

And there he sat, shaking like a leaf, besieged by the geese.

When at last he did reach home in safety—after the geese had been called to dinner—he had a wonderful story to tell.

“So you never discovered the West Pole, after all,” said Bobby.

“No,” replied Mr. Brownie, with great dignity, “but I discovered a toad-stool and that was better than nothing.”

And to this they all agreed.

How it happened little Evie could not quite make out, but one minute she was lying in bed with her eyes wide open, and the next, she thought she was high up in the sky, sitting in the moon, with brother Robbie by her side.

“Pleased to see you, my little dears,” said the Lady Moon, “but how did you manage to get up so high?”

“I don’t know,” replied Evie. “I expect we climbed up on a moonbeam.”

“Well, now that you are here, I hope you will enjoy yourselves,” said the Lady Moon, next.

“We mean to,” answered Evie, and so said Robbie. He always agreed with his sister.

“Would you like to know our names, Lady Moon?” Evie put the question with the sweetest little smile.

“No,” said the Moon, “it doesn’t matter in the least to me what your names are. I shall call you Moon Babies.”

The sky now began to grow darker, and presently a bright, silvery star peeped out and shone right over the little ones’ heads. It was just after this that the moon babies grew sleepy.

“Those chicks will soon be in Dreamland,” said the Moon to the Star.

“No, we shan’t,” said Evie; “we are only making believe.”

But the Lady Moon knew better.

The next voice that little Evie heard in her ears was not that of either the Moon or the Star. It was Nursie’s good-morning as she drew up the blind to let in the sunshine.

Once upon a time a little girl was standing at the window of a large and beautiful room. She was a Princess; she had a crown on her head, and she was dressed in the grandest clothes that could be bought, but she looked very cross.

Presently a Fairy flew in at the window, and sat down on the ledge. The Princess was not at all surprised, as there were a good many fairies about in those days, and she had seen several before.

“A penny for your thoughts,” said the Fairy.

“If you mean that you will give me a penny if I tell you what I am thinking about,” said the Princess, “I don’t want it. I have a purse full of sovereigns in the ivory cabinet where I keep my toys.”

“Oh, that must be nice,” said the Fairy; “how glad that child would be who lives in the cottage over the road if she had some of your money.”

The Princess looked quite interested at this. “How funny that you should say that,” she said; “I was just thinking about her when you came in. I do so wish that I were she.”

“Indeed!” said the Fairy.

“Yes,” said the Princess, “I watch her every day, and you can’t think what a fine time she has. She can run out to play in the street whenever she likes, and there is a dear baby for her to have games with. I mayn’t run about out of doors for fear of spoiling my clothes, and I have no one but grown-up people to keep me company. Then she sits on the door-step to eat her dinner, while I have to sit on a chair covered with red velvet, and have to be so careful not to spill anything, because the tablecloth is made of the finest damask. And nobody scolds her when she gets dirty, and she may kiss her mother whenever she likes. My mother says, ‘Don’t touch me now, Josephine; can’t you see that I have just been powdered?’ And there are lots and lots of other things that make me wish that I were that little girl. Couldn’t you make us change places?”

The Fairy looked rather grave, and said:

“Yes, my little Princess, I could make you change places, but I am not going to do so. I quite see that your life is not so pleasant as it might be, but I happen to know that little girl very well, and I am afraid that you would be no happier if you were in her place.”

“Why?” asked the Princess.

“Well,” said the Fairy, “for one thing, she hardly ever gets enough to eat, and even the little she does have, is nothing like the dainty food that is given you every day. In the winter the wind blows right through her poor thin clothes; she has no bed, but has to lie on the bare floor with a few old shawls and rags to cover her, and it is very cold and damp, as there are holes in the roof through which the rain comes. Her only toys are those that she picked up in the gutter. I could tell you more things about her, but I mustn’t stop any longer, as I have to go and amuse a child who has hurt its back and has to lie still all day. Good-bye!”

And then the Fairy spread her wings and flew away over the roofs and chimney-pots.

Though at first the Princess was disappointed that the Fairy would not let her change places with the poor child whom she had envied so much, she was very interested in what she had heard. As she grew older she found out more about the poor folk who lived in that country, and when she became Queen she did many things to help them. She never painted or powdered her face, so that her own children could kiss her whenever they liked. They only wore crowns on state occasions, and the clothes in which they played, were ones which would not spoil easily. They had a garden where they could dig and romp without being scolded; and when they in turn grew up, they brought up their children in the same way.

And perhaps that is why, now-a-days, the children of Kings and Queens look just like ordinary boys and girls, and not like the ones in picture-books.

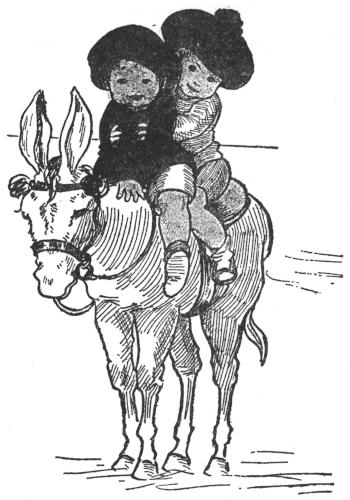

When Bob and Tommy went to the sea-side last year they had a very happy time.

Perhaps the thing that they enjoyed most of all was a ride on Neddy’s back. Dear old Neddy—he was most patient. He would carry Bob and Tommy together all along the sands and think himself well paid if a carrot was given him at the end of the journey.

One day Bob and Tommy had a fright. They were playing on a little island when the tide was coming in. Soon there was water all around them.

When their big sister, who was reading a book on the sea-shore, saw what had happened, she gave a loud cry of alarm.

At this moment up came Neddy’s master, holding the donkey by the bridle.

“I think I can help you, Miss,” said the man, quick to see what was wrong. “I’ll lead Neddy through the water, and he’ll soon bring the young masters safe to shore.”

And true enough he did.

Dear good Neddy! He was given that day a splendid feast of carrots, and I think he deserved them, do not you?

Father has promised that he will buy Bob and Tommy a donkey for their very own, and they are more pleased than ever.

Some children were building castles on the sands. Amongst the number was a little boy called Jack, and his voice could almost always be heard above the rest.

“Oh, look!” he cried, “look, Mabel, you are doing it badly! Why, it’s all crooked; you’ll have to begin again,” and leaving poor Mabel, whose face clouded with disappointment, he turned to a boy called Cedric.

“My word, Ceddie,” he said, “you don’t know how to build castles! why, yours looks like a church with a spire—you ought to make a round tower. And just look at stupid Ella! She’s hardly begun yet, and doesn’t know a bit how to do it.” And all this time Jack’s castle was getting bigger and bigger, and though he thought he was doing it very cleverly, really it was not like a castle at all. He was so busy finding fault with his playmates that he had no time to think how to do his own work properly. At last the other children grew so tired of his grumbling that they took no more notice of him, and he had to play alone until his nurse took him in to dinner. As soon as he had gone they all ran to look at his castle.

“Why, it isn’t any more right than ours,” they cried, and in two minutes they knocked it all down.

When Jack came out to play in the afternoon he cried because his castle had been spoiled.

“Children,” said Mother, one morning, “I want you to take a basket of eggs to Mrs. Brown at Rose Cottage, with my love.”

Tom and Effie were quite willing, for they were very fond of Mrs. Brown. The walk there was lovely—the skies were blue and the birds were singing their sweetest songs.

At last they reached the garden gate. “Oh,” cried little Effie, who was carrying the basket of eggs, “just look, Tom! There’s a Billy goat in the garden! Let us go and make friends with him.”

“So we will,” said Tom.

They had a goat at home and so were not in the least afraid.

But Billy looked very fierce as the children drew near, as much as to say, “Who are you?”

Then he made a sudden rush at them. Effie in her fright, nearly flew towards the gate, dropping her eggs on the way. Poor Tom, however, did not escape so easily. The goat butted him into the air and soon the poor little fellow lay sprawling on the ground.

Mrs. Brown, hearing their cries, quickly came to their help, and soothed away their fears.

“How dare you be so rude, naughty Billy?” she said to the goat.

And Billy looked quite ashamed of himself, as well he might.

Since that day, he has learnt better manners, and now he is very pleased to see the little pair when they come to pay a visit to Rose Cottage.

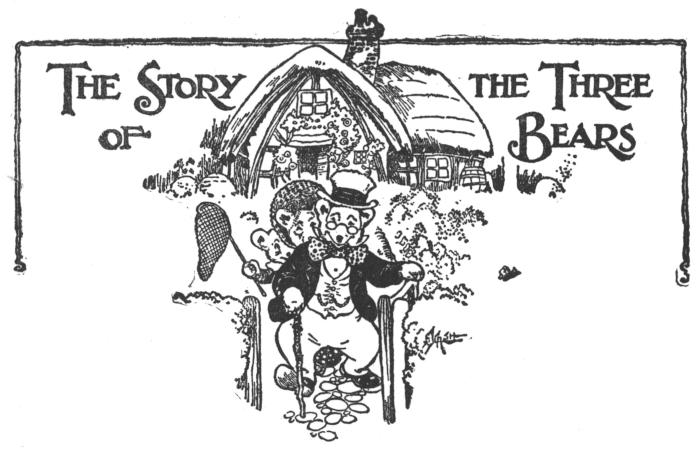

Once upon a time there were three bears. They lived in a cottage by the wood.

First you saw a little green gate opening on to a garden path with a box-border on either side. Behind the box-border were all sorts of sweet flowers—pinks, gilly-flowers, and pansies, boy’s-love, rosemary, and sweet lavender. Behind the flowers grew gooseberry and currant-bushes, and behind the currant bushes cabbages, carrots and onions for dinner.

The straight path led to the cottage door all covered with roses and honeysuckle. Such pink roses and such sweet honeysuckle, just the sort the bees love best, for bears like honey, and the bee-hives were behind.

The door stood open to let in the air and the sunshine, and because doors were made, in those days, to let people in, and not keep them out.

Inside was the nicest, cleanest kitchen you ever saw, with a table in the middle, as white as soap and scrubbing could make it. Against the wall stood a tall dresser covered with bright pewter plates, hanging cups and jugs, and all things such as bears might use. A pepper-pot, you may be sure, and a tureen with string and odd things in it.

The three chairs just suited, for there was a great, huge arm-chair for Mr. Bear, who was big and heavy; a middling-sized chair for Mrs. Bear, who was middling-sized; and a small, wee chair for little Master Bear, who was small and wee.

The fireplace, with its open chimney (it had a green frill on a string under the mantle-shelf) was the cosiest in all the land, as Mr. Bear very well knew when he smoked his pipe there on a winter night.

In one corner of the kitchen was a door that opened on to the stairs, and up the stairs they went to bed every night. The bedroom had three beds in it that any one might like to see. A great, huge one for Mr. Bear, a middling-sized one for Mrs. Bear, and a small, wee one for little Master Bear. All was sweet and airy, and the window looked out into the garden, and the roses looked in at the window, and the wind whispered in the trees outside.

Now it happened one summer morning that Mrs. Bear got up earlier than usual to make the porridge for breakfast, and it happened, too, that when she put it out to cool in three willow-pattern bowls on the table (a great, huge bowl for Mr. Bear, who was so big; a middling-sized bowl for Mrs. Bear, who was middling-sized; and a small, wee bowl for little Master Bear, who was small and wee) that she went to the foot of the stairs, and called aloud to Mr. Bear: “Make haste down, and we will go for a walk in the wood while the porridge is cooling.”

“Very well, my dear,” said Mr. Bear, in his great rough voice; and then down he came, with little Master Bear scrambling down behind him.

Now when great, huge Mr. Bear came down the stairs, you can be sure that he caused every board in the cottage to creak, and the thud of each tread was so very heavy that all the cups on the dresser shook. That tells you how huge and big he was.

Mrs. Bear heard him coming and took her bonnet from its peg, and when the strings were tied beneath her chin, and Mr. Bear had taken his thorn stick from the corner, and little Master Bear had found his butterfly net, they all set off in the wood for a walk, clicking the gate behind them.

Such a lovely June morning for an early walk. The birds sang, the breeze fluttered Mrs. Bear’s skirts and Master Bear’s butterfly net, and the dew was on the grass and hung all shimmering in the cobwebs.

As to the wood, it was cool and shady, and the three bears were soon out of sight.

Then there came to the gate a little girl named Silverhair. She was hot and tired, and said to herself: “Here is a sweet cottage; perhaps the good woman who lives here will give me some milk and a rest. I’ll knock at the door and see.”

So up the straight path she walked, with the box-border on either side.

“Rat-a-tat,” she knocked.

But nobody said “come in.”

“Rat-a-tat-a-tat” once more, but nobody said “come in.”

Then again louder than before, but all was still. So, being very hungry, and not so shy as she ought to have been before such a sweet, open door, in she peeped, and then in she went, and the very next minute she was tasting Mr. Bear’s porridge. But it was too hot, and she let the spoon fall with a clatter on the table. Then she tried Mrs. Bear’s porridge, but that was too cold, and then she went to little Master Bear’s porridge, and that was so nice, neither too hot nor too cold, that she ate it all up till she could see the blue pattern at the bottom of the bowl quite plain.

That was sad, for it was not her porridge! Little Silverhair was quite naughty now!

After her breakfast she felt how tired she was, so she sat down in Mr. Bear’s arm-chair, but that was too hard. Then she sat down in Mrs. Bear’s chair, but that was too soft; she thought it quite stuffy for so warm a morning, and she was now hard to please, for Mrs. Bear’s chair was covered with pretty white chintz with rose-buds on it, and what more could she want?

But she was very naughty now! She sat down quite roughly in little Master Bear’s chair, and sat the bottom out, and was not dismayed! No, up she jumped, and looked about till she saw the door in the corner. Then she tripped upstairs, and threw herself down on Mr. Bear’s bed. But that was too hard. Then on Mrs. Bear’s bed, but that was too soft. And last of all she tried little Master Bear’s little wee bed, and that was neither too hard nor too soft, but just right.

In two minutes she was fast asleep, with the breeze from the window blowing on her soft silver hair.

Now between conversation and butterflies the three Bears had let the time pass, till suddenly Mrs. Bear saw by the shadows of the trees on the grass that the porridge must be cool.

“We must turn, and walk faster home,” she said.

“Very well, my dear,” said Mr. Bear in his great, huge voice. But the birds in the wood did not flutter, for they knew quite well what a kind heart he had, and how he kept crumbs on his window-sill.

When they got to the gate that they had clicked behind them, it was open, and Mr. Bear hurried on to see who had come. He hurried on till, when Mrs. Bear and the little one came in, he was standing before his porridge bowl with a sad face, and his spectacles pushed on his forehead.

“Someone has been at my porridge,” he said, very loud indeed.

Poor Mrs. Bear! She looked at her own bowl, threw up her hands, and said in her middling-sized way, “Oh, deary me, someone has been at my porridge!”

Then little Master Bear tossed his butterfly net into the corner and ran to the table, but though he tipped up his bowl till the pattern was plain to see on the bottom, not so much as one drop of milk could he get from out of it, and he cried in his shrill little voice, “Someone has been at my porridge, and has eaten it all up!”

Then there was great uneasiness in the mind of Mr. Bear, and he turned to his chair and saw how it was pulled from the wall in a very unusual way. “Someone has been sitting in my chair,” he said.

Mrs. Bear turned to hers, and saw that the cushions were all in disorder. “Oh, deary me!” she said, “someone has been sitting in my chair.”

Then Master Bear, leaving his empty bowl, hustled up to see; and now it was “Oh, deary me,” and no mistake, for when he saw his little chair all broken and spoiled he cried out at the top of his wee voice, “Someone has been sitting in my chair, and has sat the bottom out!”

No time was to be lost in such sad straits, and Mr. Bear had his foot on the stairs before Mrs. Bear had so much as decided how the little chair could be mended. She felt sorely puzzled, but, picking up her gown in front, she followed Mr. Bear up the stairs, while little Master Bear clambered, heavy-hearted, up behind her, holding on very tight to the back breadth of her skirt, for who could tell what would happen next!

Once in the room, they all went to the big bedstead that had been made so strong for Mr. Bear by the village carpenter, who knew how to please his customers.

When they saw the clothes so tumbled, it was no wonder that Mr. Bear should thunder out, “Someone has been sleeping on my bed!”

Poor Mrs. Bear! she turned round to look at her own white bed, with its pretty dimity curtains, and she called out in her middling-sized way, “Oh, deary, deary, deary me, someone has been sleeping on my bed!” Her feelings and the counterpane were sadly ruffled.

Master Bear then left go of her gown, and crept away to his own little corner.

And what did he find? Fast asleep, with her hand tucked under her cheek, and her hair all tossed about on the pillow, lay little Silverhair, dreaming of porridge and broken chairs. How pleased the wee Bear was! He piped out in his small, wee voice, “Someone has been sleeping on my bed, and here she is fast asleep!”

But the last word sounded so loud in Silverhair’s ear, that it woke her with a start, and before the three Bears could tell what to do next, she had jumped out of bed and then out through the window, brushing the dew off the roses as she went; and those three Bears never, never, never saw her any more.

One night when the moon was big and round, Baby Blue-eyes was lost. Dear, oh, dear, there was a terrible upset in Babyland!

Said Chubby-face, the Infant Queen, “I’m not going to rest till Blue-eyes is found.”

And starting forth with Rosy-cheeks, her little maid-of-honor, she began her search.

At last—oh, what joy filled her heart!—she found little Blue-eyes fast asleep near a toad-stool!

“We won’t waken her, she is sleeping so sweetly,” she said.

And so the pair of them, (Chubby-face perching herself on the roof of the toad-stool,) kept guard till Blue-eyes awoke with a smile.

My name is Kitty. If you ask, “Who gave you that name?” I am sure I could not tell you.

I hardly know where I was born, but they told me that I first saw the light in a wood-shed. I never remember my father, but I have very happy memories of my kind, gentle, gracious, good mother. Her name was Fluffy. There were four of us altogether—I mean four kitten-babies—and I was the youngest—at least, so I was told.

I was only about three weeks old when a great sorrow came into my life. One morning a big, burly, but ever so kind gentleman came to the wood-shed and said something about his pretty daughter, who had recently “gone to housekeeping,” and that, being alone all day, she would dearly love to have a bright little kitten for company. And I was chosen, so off I had to go.

I was taken gently by the neck and lifted into what looked like an egg-basket, and in a few minutes I was brought to a sweet little home. I fell in love with my new mistress at first sight, and as for my new master, he treated me ever so kindly, and I learned to love him very sincerely.

I had never tasted milk—in fact, I didn’t know what it was, whether it was blue, grey, white, brown, or red.

Soon after my arrival my new mistress (who bore the sweet name of Lily) brought me some white liquid in a saucer. I wondered what it was. As she watched and waited, I did the same. At last she took my wee little head in her long, thin, white hand and dipped it in the white liquid. I thought it was rude. My mouth, nose, and lips being covered with the white stuff, I quickly licked it off. What else could I do?

When I tasted the fluid I found out how nice it was, and began to lap it up at a great rate. Then it was I found out it was milk she had given me. I got quite fond of it, and had a regular supply night and morning. And I always said “Thank you, ma’am,” by giving a gentle purr.

Then at dinner-time my young master, Mr. Fred, gave me some choice, dainty bits off his plate, which I greatly enjoyed.

When I arrived at this pretty cottage, I was so small, I looked just like a bundle of grey worsted; but day by day I was getting bigger, fatter, and nicer-looking—I was indeed. Don’t think I’m vain—I’m not; but when a sweet young mistress says “Pretty Kitty” twenty-seven times every day, what can I think but that I am a fascinating, good-looking little puss?

Soon after my home-coming, another big sorrow came into my kitten life. My dear young mistress was taken seriously ill, and had to go to bed—and stay there. The doctor was called, and came nearly every day. I was nearly broken-hearted, and every chance I got I rushed upstairs, so as to tell, in my simple, loving way, how sorry I was for all the trouble that had come to my dearest earthly friend. I sprang on to the bed, walked over the counterpane, and reached the white pillow on which lay the head of my sweet young mistress. I purred very gently, rubbed my nose against her cheek, and said, in the best possible way (to a kitten), “How sorry I am! Do make haste and get well again; I do miss you so!”

Once or twice I’m afraid I woke her out of a sweet sleep, but how should I know she was asleep? Nobody told me. So I was seized by my neck, and put out of the room a good many times. But every time the kind nurse opened the door, I rushed in again, sprang on the bed, and said, “I’m so sorry,” ever so many times. And sometimes, in the dark night, or early hours of the morning, I would creep up to the bedroom door, and cry as loudly as I could.

At last a crisis came, and to me it was a big crisis—my third trouble, and I was only six weeks old! I was to be sent away, because I was so troublesome. I thought it was very, very hard, and I cried about it for three and three-quarter minutes, and thirteen long seconds after that. Wherever was I to be sent?

One evening a tall, kindly-looking gentleman came to our house, and my young master said to him, “Father, can you take charge of Kitty for a few days, until Lily gets better?”

“All right, my boy,” was the cheery reply. I liked his voice and manner. My fears were soon set at rest, for I felt sure he would make my short visit as cosy and comfortable as he possibly could. A few minutes later he took me up by my neck, laid me gently on his arm, and took me out into the dark and stormy night. But I wasn’t afraid, not one little bit, for all the way my new master kept saying, “Poor little Kitty.” But it was the way he said it that made such an impression on me.

We had not far to go—only about three minutes’ walk. My new home was, if possible, even better than the one I’d left—so cosy-comfy like. Having had my supper, I lay down on the hearthrug before a big fire, and was soon fast asleep. But I got a rude awakening, and nine times as big a fright!

I had only been asleep about a quarter of an hour when I felt something cold touching my nose. I wondered what on earth it was. Looking up, I saw a big Tom-cat staring at me wildly and jealously. He seemed to say, “What are you doing here? Don’t you know you’re sleeping in my place? This is my home, not yours!”

I sprang to my feet and faced Impy. He was a big, black fellow, eight or ten times as big as I was, with eyes flashing like automobile lights. And yet, strange to say, I wasn’t a bit afraid, that is, not after the first startling. I stared at him, put my little back up, and spat at him—real hard! Yes, and I frightened him too, for after a low growl he turned away, scowling at me, and went off to the kitchen to tell Nellie, the maid, all about me. So I lay down to sleep again, and enjoyed a good night’s rest.

The next day I had another fright. At my new home lived a big collie dog, called Bunty, and the next morning I had to be introduced. Bunty and I were soon fast friends. Instead of scowling at me as Impy had done, he came and looked at me ever so kindly, and kissed me, as if to say, “I like the looks of you; let’s be friends.” And we were, all the time I stayed there. He often gave me warm kiss-licks, and loved to have me play with his long, shaggy tail, climb over his back, and lie by his side and purr.

It was very nice, and I shall love Bunty all the days of my life. If ever I get married—and I don’t see why I shouldn’t—I shall dearly love to have Bunty come and stay with us, and make his visit as long as he possibly can. He will always be a welcome guest.

But one day I nearly lost his love and affection. It came about in this way. Wandering in the kitchen one day, early after dinner, I saw Bunty busy enjoying a mutton-bone feast. I did long for a bit. So I made a dash for Bunty’s bone, yes, and I got it, too! Off I ran into the dining-room with the bone in my mouth, the big collie chasing me. How I managed to carry it I don’t know, for the bone was nearly as big as I was. I hid, but Bunty found me, and got his bone; the wonder is, he didn’t bite me for being so greedy. As it was, he only growled, and was ever so kind and forgiving—later on.

I soon found out that my new master was a big tease. He used to tumble me over on my back and tickle me so earnestly, I had to scratch and bite him real hard, so as to defend myself. But he did not seem to mind—not he!

One night I got lost. When the front door was opened I ran out into the road and had a merry scamper. I tried to find my way back, but couldn’t. What was I to do? It was a cold, bitter night, and I was a stranger in those parts. Still, I felt I ought to do my best. So I ran up to what I thought was my new master’s front door and cried. A kind little girl let me in, and I soon found I was in the wrong house. I did not mind that so much, so long as I had got in somewhere. They were very kind to me, gave me some milk, and said “Pretty Pussy” a good many times.

The next morning Nellie, the maid, called over the garden wall, “Has a stray kitten come to your house?”

“Yes,” replied the little girl, Kathleen. “Do you want her?”

Of course they did, and soon I was safely lodged at Jasmine Villa. But when my dear young mistress got well, I joyfully went back, and said how grateful I was to get home again.

There is a little Dutch village called Volendam. Most of the men are fishermen, and wear tight blouses of crimson or blue, and large, baggy trousers coming down to their ankles.

The little boys, even the tiniest ones, are dressed just like their fathers and their big brothers. Sometimes they are to be seen walking up and down the narrow streets of the village with their hands in their pockets, trying to look like the men.

The women and girls wear white lace caps and a great many woolen skirts—sometimes as many as eight or ten; and the more they wear the more they are admired by their neighbors. Even the tiny girls of two or three years old are dressed just like their mothers.

All the people wear wooden shoes, and as most of the streets are paved with tiles the people make a great noise as they clatter up and down. These wooden shoes look very big and clumsy, but the children manage to run about in them just as easily as you do in yours.

Nearly every woman and girl in Volendam wears a necklace of coral beads. And nearly every man and boy wears two big silver buttons; the richer a man is, the larger are his silver buttons.

The Dutch people keep their houses and streets very clean. They are always scrubbing their houses inside or out, and the little girls have to help in this as well as their big sisters.

Eveline, Arabella, and Peg were having a great discussion, seated on a large cushion where their mistress had left them when she went to bed.

“It isn’t fair!” exclaimed Arabella, shaking herself. “Here I can scarcely bend because she has stuck a pin right through me. It goes in at my waist and out at my back, and the bit that sticks out at my back, she hung my sash on and thought it wonderful!”

“Yes, she treats our nice, soft bodies just like pin-cushions,” agreed Eveline. “And her mother has given her a nice work-basket with needles, scissors, and a thimble in, and plenty of tapes and buttons, and she is always trying to make her sew neatly, yet just look at us!”

“But what about me?” chimed in wooden Peg. “My master hasn’t a work-basket, and when he wanted to stick this piece of cloth on my head for a cap, he just got a tack and hammered it in! And there it will remain until he wants a tack again, and then he’ll know where to find it.”

“Well, of course your feelings are not so keen as ours,” sniffed Eveline. “I am not very big, but I have five pins in me, and one is to keep my stocking up, and she has tied a piece of cotton so tightly round the other that it’s cutting into my leg.”

“Well,” said Arabella, “I’ll tell you what we’ll do. To-morrow when she picks us up we will make all these pins scratch her; we will scratch her so much that she will be glad to take them all out and put buttons on.”

The next day when Doris picked up Eveline she suddenly screamed, “Oh, mother, see how I have pricked myself on this nasty pin! Oh, it does hurt!”

Mother looked grave.

“If my little girl would try to sew as mother wants her to, there would be no nasty pins, dear.”

Doris thought a moment and then picked up Arabella. There was another cry, and a scratch on her wrist. “Oh, mother,” sobbed Doris, “they have hurt me all over. Now I won’t put any more pins in, I won’t really! I’ll start now and learn to sew, mother.”

So Doris put tapes on all her dollies’ clothes. Indeed, she even put tapes on Peg’s hat and tied it under her chin for her, and Jim was very glad, because he was wanting the tack.

Isabel Rayfield.

BILLY’S GOT A DRUM