Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

THE PRODIGAL'S RETURN.

FISHER-LIFE AT THE LAND'S END.

BY

MRS. GEORGE GLADSTONE

AUTHOR OF "NORWEGIAN STORIES," "FIRESIDE STORIES," ETC.

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56, PATERNOSTER ROW; 65, ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD;

AND 164, PICCADILLY.

PREFACE.

SOME weeks have elapsed since the author of this little story was

separated by death from a dear and honoured mother, to whom she

submitted all her literary work, on whose criticism she relied, and in

whose judgment she placed implicit confidence. "Waiting for Sailing

Orders" was the last story which passed under her aged mother's review;

the title had a special charm for the latter, who knew not how soon her

summons would come, but always kept her lamp trimmed, and was prepared

to meet her Lord, at whatever hour He sent His summons.

Her children were standing round her death-bed, wondering if

consciousness yet remained, and how long the spirit would linger

ere it fled to the mansions of the blest, when she said, in such

clear and distinct tones that all in the room could hear, "I am

waiting,—waiting,—waiting, for my sailing orders to come."

Three days later her sailing orders came, and the sweet smile which

lingered in death made those who were left behind rejoice in the midst

of tears, because it seemed to speak of the joy and bliss into which

the spirit entered when the "waiting" was over and a long eternity in

view.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

WAITING FOR SAILING ORDERS.

MACKEREL FISHING.

THE fishing village of Newlyn, which stretches about a

mile along the west shore of Mount's Bay, in Cornwall, presented a busy

scene one morning in April of the year 1862. The mackerel season had

just begun, and some of the boats came in heavily laden.

"What's the take?" asked an old woman of a sailor.

"A thousand downwards," was the reply, which meant that the number of

mackerel in each boat varied from that number to one hundred, fifty,

twenty, ten, five or not one.

In Mount's Bay the boats are large, and among the safest and best craft to be found on any fishing coast. They each carry a crew of seven men, who share equally in the profits, after a certain portion has been set aside for the use of the vessel and the nets.

The "Mary Ann," which brought in the thousand mackerel, belonged to John Trevan. He was a man much respected in Newlyn, for all his dealings were fair and upright. He had for partners six other fishermen, of whom he was the captain, and who deferred to him at all times, placing the most implicit confidence in his judgment.

As the ship's boat containing John Trevan and his mates came near the shore, the agents of several London fish-dealers waded through the water to bid for the finest mackerel. The bargain was soon concluded to the satisfaction of all parties; then the fish were thrown into baskets and carried on to the sands, where they were turned into a tub of water, washed, packed neatly in the same baskets, and carried away in carts to the railway. The hake, cod, conger eels, a few soles, and some very small mackerel that remained, the crew divided with their captain.

Mrs. Trevan was awaiting the arrival of her husband with her basket. Every Cornish woman owns a basket of some sort: those carried by the fish-women are called "cowels," and are supported on the back by a band passed round the forehead.

"We've had splendid sport, Philippa," said John Trevan to his wife, "and there's a fine lot for home use. Let's have a conger pie for to-morrow. I'll be in to dinner; but we must hang our nets to dry first, and clean up a bit. The boat's off again at six. I can afford to take my holiday to-morrow cheerfully, after my good fortune of to-day."

"Yes, John, and if only we can have fine weather like this, you'll enjoy it," answered Mrs. Trevan.

"We must work hard all the afternoon, for the nets have got sadly broken. Father will have more than he can do, a boat ran clean through one of mine."

Philippa Trevan gathered up her share of fish, and placing it in her basket, walked slowly up the narrow road from the sands, towards Street-an-Nowan, or New Street, close to which she lived.

Newlyn is the principal fishing station in Mount's Bay. It is divided into two parts, which can only communicate, the one with the other, by the sands, unless you go far into the country, over the high hill which leads to the church-town of Paul. In ordinary tides the sea comes nearly up to the stepping-stones, but sometimes it dashes against the cliff, and renders the shore too dangerous to be crossed, even in a boat. The houses are irregularly built, and the streets are narrow, ill-paved, and in many parts run along the top of the sea wall, with no protection from the waves except what is afforded by a strong open iron railing.

Mrs. Trevan turned up narrow Rag-stone pathway before she reached the end of New Street, and mounted four steps which led into a comfortable sitting-room in a whitewashed cottage. The small door to the right opened into the best parlour, at the back were the kitchen and grandfather's bedroom, and overhead three more rooms.

An old man, a very old man, with snowy hair, sat in his arm-chair reading out of a large printed Bible; and in spite of the difference of years, his features were so like Mrs. Trevan's, there was no difficulty in recognising the relationship of father and daughter which existed between the two.

"You're soon home, Philippa," he said; "have you good news?"

"Very good, father; John has taken a thousand mackerel, and sold them well. He says there will be more work than you can do to mend the nets."

"I'll try my best, Philippa. We expect to mend them up every day. The Lord Jesus isn't here with his disciples. I'd just read these words when I heard your footstep: 'Simon Peter went up, and drew the net to land full of great fishes, an hundred and fifty and three: and for all there were so many, yet was not the net broken.'"

"No, He isn't walking in our midst as in those times, father," said Mrs. Trevan, "but he's just as near to us in spirit as he was then. I never see John start without commending him to God in Christ. I think as I grow older my Saviour seems to come nearer. But for his living presence in my heart, I could not go about my daily work as cheerfully as I do. Remember my boy, my first-born, and the awful uncertainty about him. Oh, father, I try hard to think of what my Saviour suffered on the cross for me, so as to get strength to endure my own sorrow with a lighter heart."

"Poor Philippa," answered the old man, tenderly. "Be of good courage. God will hear our prayers. I'm on the mountain-top of my pilgrimage, very soon I shall be running fast down the other side, entering into the dark valley and shadow of death; but I believe I shall see the lad before my sailing orders come."

"You've such strong faith, father. Mine is dimmed sometimes with waiting and longing; but only dimmed for the moment, for through all my bitterness of spirit, I remember that my Heavenly Father loves and cares for my poor misguided son. But here come the children from school."

Mrs. Trevan had just time to take up her basket and go hurriedly into the kitchen, drying her tears, when Dorothy and Judith, her twin daughters, entered, and coming up to their grandfather, kissed him affectionately. The old man returned their caresses, for he loved these girls next to, if not as well as his own daughter. He lived over past days with them, for they never wearied of hearing of the perils by land and sea, which had overtaken him during his long life.

Dorothy and Judith would complete their thirteenth year on the morrow. They closely resembled one another in features, but were unlike in disposition; for while Dorothy was high-spirited and quick-tempered, Judith was mild, tractable, and quiet. Their figures were upright and well-formed; they had bright jet black eyes, and long curling hair, fresh complexions, and frank open faces. They wore the gipsy hats made of beaver which are now out of date, short light-coloured print dresses, dark-blue knitted stockings of their own making, and strong leather boots.

"Have you done well at school this morning?" asked their grandfather.

"Yes, very well," answered Dorothy. "I did my sums so quickly that teacher said she was pleased for me to have a holiday to-morrow. She remembered that we spent our birthday at the Land's End last year with great-uncle Thomas Nance. You know Judith is always good at her lessons, grandfather."

"That's right, Dorothy," answered Captain Nance, for so the old man was called. "Do try, there's a good girl, to deserve the praise you've just bestowed on your sister. Let Judith be able to say of you, 'She is always good at her lessons.'"

"I do try, grandfather, to be attentive, but I can't always be the same. Judith hasn't such a nasty temper as I have to worry her."

"There's one cure for it; we may all go to the Great Physician, my little girl. How you will enjoy yourself, Dorothy, when to-morrow comes! I didn't think I should live to go with you again; I shall be fourscore years and ten if God spares my life until the 9th of November."

"That is a long, long time compared with our thirteen years," said Dorothy.

"It is a long time to have lived, my dear. I shan't be much more tossed on the billows, for the storm of life will soon be over, and my poor old weather-beaten bark will be safely landed on that happy shore where the wicked cease from troubling, and the weary are at rest."

"But, grandfather, what shall we do without you?" asked Judith, laying her soft cheek on the old man's. "We are so happy together."

"So we are, dearie, but it's not the happiness of yonder world. Don't want to keep me here, little one; you must try and be very glad when the old tar has his sailing orders."

"Come, children," called their mother, "lay the table for dinner. I have plenty to do to make ready for your birthday trip to-morrow."

Dorothy and Judith were soon busy in household matters, and we will leave them so engaged while we give a short account of the family to which we have introduced our reader.

THE GREAT SORROW.

JOHN TREVAN was among the most prosperous inhabitants of Newlyn. He was an industrious man; his wife was thrifty, and he had a small family to support. It consisted of one son, who had wandered far away from his father's house, eight years before our story commences, and the twin daughters.

John Trevan married Philippa Nance, at the age of thirty-five. He brought his wife, who was six years his junior, to the whitewashed cottage we have described, where his parents had lived before him. Her father came too, for he could not be separated from his only remaining child. When Philippa consented to marry John Trevan she stipulated that her well-beloved parent should share her future home.

"He will be no burden upon you, John, for he has enough to keep him," she said.

To which her future husband replied, "He would be welcome for your sake, Philippa, were he penniless."

A boy was born to them at the end of two years. This event brought great joy to the little circle; but as the lad grew in years, his parents had many reasons for deep anguish regarding him. He was named William, after his grandfather; and known to all in Newlyn as "mischievous Willy." He was brought up carefully, and taught to fear God; but he spurned the good, and clung to the evil; yet sometimes, when his mother took him into her room, and knelt in prayer to God, with him at her side, his tears would come, and he would say,—

"Mother, it is so hard not to be naughty."

And she answered him, "I know it, my darling boy; but do not trust to yourself, pray to God, Willy, to make you a better lad. Ask your Heavenly Father to give you His Spirit to help you, and change your heart of stone to a heart of flesh. He will not refuse to hear your prayer if you ask in Christ's name."

For one or two days after an outbreak Willy was more obedient, and then he began to be tiresome again. He had no regard for truth, and played truant so often that at last either his father or mother took him to school every morning, and gave him into his teacher's charge, before they went about their daily work.

When Willy reached his tenth year, his twin sisters were born, and for a few weeks all went smoothly with him. He loved the little baby girls, and felt very proud when his mother allowed him to hold one of them in his arms, but this novel pleasure wore off, and he was again running wild with unruly boys.

"I must send him to sea a year or two hence, under some wise captain," said John Trevan to his wife, many times. "I can't keep him at home if he does not turn over a new leaf. He'll have to think when he has to go before the mast, and be obliged to obey; and he'll be quite away from his bad companions."

But the mother clung to her prodigal; her love for him grew all the more because Willy's friends were so few, and because he was the child of so many tears and prayers.

A hundred years ago smuggling was rife in Cornwall, and contraband goods and spirits were netted instead of fish. Then Wesley and Whitfield roused the people up to better things by their preaching, and taught them to reverence God and believe in His Son. Willy had heard many wonderful stories about these smugglers, and he thought it was just the sort of life that would have suited him. He wished those old times were not over, for he disliked the hard work of a fisherman's life.

So time passed on until Willy reached his fifteenth year. On the morning of his birthday, he quarrelled with his father, and refused to help him dry his net. John Trevan grew angry, and high words passed between the two. The end of it was, that the boy packed on his clothes, and when his father went out fishing and the rest were asleep, crept to the old teapot where his mother kept her money, and having robbed her of two sovereigns, stole away from his home, and took the road towards Plymouth. He walked some miles before he ventured to get a lift in a waggon, lest he should be recognised and taken back to Newlyn. At Plymouth, he engaged himself to a captain who commanded a large ship bound to Lagos, in Africa; but a bad unprincipled man. Thus far he had been traced, and eight years had passed away without bringing him home again, or a message or letter being received from him.

Mrs. Trevan was bowed down with grief when she found her son had left his home without bidding her farewell. So soon as she discovered that her little store of money was gone too, and thought of her first-born as a common thief, she moaned out in the bitterness of her sorrow, "My heart will break. Oh, Willy, Willy! What have I done that you should treat me so cruelly?"

John Trevan was indignant. "Let him go," he said; "I do not own a thief as my son."

But when year after year ran on, he forgot Willy's faults, and only yearned to clasp him in his arms once more. No family prayer ever closed without remembering him. His mother felt she could give him up if only she knew what fate had befallen him, and that he had turned to God.

The little girls retained a vivid remembrance of their brother; they hushed their voices when his birthday came, it was so differently kept to their own; there was no holiday-making. Their mother looked sad, and always went out alone before breakfast, up the hill behind Newlyn, into the fields, to a point which commanded a view of the broad ocean. Her birthday prayer for Willy was that he might come home, not as he left her, but with a new heart and a right spirit.

The little circle at Newlyn would have known but few cares had Willy been with them, a steady well behaved boy.

"It's doing us good," John said to his wife, when they reverted to their great sorrow. "Perhaps we should have grown away from God if our boy had given us no trouble; but now He's chastening us, and teaching us the value of having a Father in heaven, to whom we can tell out all our troubles. I am like your father, Philippa, I believe God will help Willy, as He has helped us, and bring him home again."

The mother sighed when her husband spoke thus, and answered, "God grant it may be so."

————————

THE OLD TAR.

"GRANDFATHER, make haste," said Dorothy and Judith, tapping at the old man's door, next morning. "It's past seven, and breakfast is ready. We're to go away at ten o'clock. Father has ordered the cart to come punctually."

"Many happy returns of the day to both of you," answered Captain Nance, opening his door. "Come in, my dears, and let me say my birthday wishes here. I believe I was up the first in the house this morning, and see I've got on my best rigging. It's only on such gala days as these that I dress up my old weather-beaten hulk so grandly; and I've put on all my medals, too, in your honour."

"You look fine, grandfather," exclaimed the little girls. "You must tell us some old stories about them to-day."

"So I will, little ones; I'll try and make your day cheery. I've done nothing but think about you since I opened my eyes this morning. I've been talking to the Lord about you: I've asked Him to give you a good passage through life."

"Thank you, grandfather," said Dorothy, throwing her arms round the old man's neck and kissing him. "But now you must come, for father and mother will be waiting. After breakfast we will go into the best parlour, and you shall tell us all about yourself."

"Oh, yes, do, grandfather!" added Judith. "But now come with us."

Each of the little girls took possession of a hand, and led the old man into the everyday sitting-room.

Captain Nance was quite accustomed to be so escorted, and he was just as submissive after the morning meal was ended. He allowed himself to be guided into the best parlour and seated in an arm-chair, while Dorothy and Judith placed themselves at his feet to hear some passages of his eventful history. They knew it well; certain parts of it they could repeat from memory, but still they liked to listen, for their grandfather invariably added some detail which gave fresh charm to the story.

"We've a whole hour before us," said Dorothy; "so begin directly, please, grandfather. Just say off quickly what happened to you, and then let us ask questions."

Captain Nance cleared his throat, and began, in these words:

"I have borne the battle and the breezes of a life on the sea for more than fifty years. I have been in four quarters of the world, and have been four times shipwrecked. I have crossed the Atlantic thirty times; I have lost four sons at sea; I have been in four battles at sea; I have saved two men from drowning. I have been a standard-bearer in the temperance army for more than forty years, and I have belonged to the Band of Hope for nigh upon a quarter of a century. Now I have coiled up my ropes, and am safely moored in a sailor's cot with those whom I love, and am patiently waiting for my sailing orders, bound on a long, long voyage, from whence there is no return—for ever and for ever. Amen."

"Now, Dorothy, which part do you want to hear about?" asked Judith, breaking the silence which fell over the little party after the "Amen."

"I know," replied Dorothy, whispering into her sister's ear first, and then repeating the same words aloud: "Grandfather, tell me about my uncles who were lost at sea, if it won't make you very sad."

"No, no, child: I ought not to be sad, an old tar should be a brave man. Thank God, your grandmother didn't live to see those days. I buried her in the churchyard yonder, at Paul, long before the sea swallowed up my sons. They were fine young fellows, and God-fearing men; they prospered and rose rapidly in the service, until they became master mariners. Three were lost within a few weeks of one another. They were outward bound to foreign parts. I can't tell you how they died: no one on this earth knows what they suffered, for ships, captains, officers, passengers, and crews, went down. But though they didn't reach the harbour of refuge here, Christ, the great Harbour-Master, came alongside and welcomed them into glory. Ah! My children, I'm proud to think of your uncles as honest Christian men, and as now safe with Christ.

"I blessed the name of the Lord even when my heart was bowed down with grief," said Captain Nance, reverently, after a pause. "Learn to thank God, my dear grandchildren, when He gives and when He takes away."

"And what of my fourth uncle, grandfather?" questioned Dorothy.

"My fourth boy, my Benjamin, yet remained to gladden my life. He was in America when the news of his brothers' death reached him. I expected him to return home in a few months' time, so I wrote and told him how I longed to see him, for he was my only son. He sent me a letter filled with words of comfort, and directed me to lean on the Rock of Ages in time of storm. He said he would be homeward bound earlier than he expected, and that a few days after his letter reached me, he would probably set sail.

"I counted how long it would take him to reach Plymouth if the weather were in his favour. I made allowance for contrary winds, and decided when I might expect him here. A week before it was possible for him to come, a great storm arose, and the Master was not in the ship to say, 'Peace, be still.' But He was watching; he hadn't forgotten my brave boy; he had prepared a mansion for him, and his Heavenly Father wanted him to fill it. The ship went down, and only two of the crew were saved; my boy, and all on board besides, perished; they told me he was praying when they last saw him. I could only murmur in the first days of this new sorrow: 'If I be bereaved of my children I am bereaved.'

"My fifth child was spared to me. Your mother, my dear Philippa, yet lives to cheer my last days, and God has given me your love. I thank him for these mercies."

The old man's tears were falling fast as he said these words. He did not often weep, but on this birthday morning, the past came up before him, and while thinking of his grandchildren, he had pictured to himself what his sons would have been to him in his old age had they lived.

"Grandfather, I'm so sorry: I ought not to have asked you to tell me about my dead uncles. Please forgive me," said Dorothy.

"I've nothing to forgive, dearie. Though my tears fall I do not fret, for I know my Heavenly Father has ordered all things for the best. I shall soon be with my lost ones. I'll not start sheet nor anchor until I get a clear meridian observation of Canaan, then I will furl sails and 'lay to' until my Saviour calls me to himself, and allows my old weather-beaten barque to enter the harbour."

There was a pause of some minutes, and then Judith said, "It's my turn now, grand father, and I'm going to ask you how you won your medals."

"And I'm going to ask you to get ready," called out John Trevan, opening the door. "Fetch your cloaks and hats, children, while I wrap your grandfather up in his warm coat, for the wind is cold, and we can't afford to let him run any risks."

All was now busy preparation; and in less than half an hour, the party were on their way to the Land's End. Captain Nance, Dorothy, and her father, sat on the front seat, and Philippa, with her daughter Judith, and a large basket of provisions between them, were packed in behind.

————————

THE LAND'S END.

THE first part of the road from Newlyn to the Land's End runs through charming scenery. The hedges are rich in ferns, foxglove, and wild flowers, and the trees are well-grown. But as you near the most westerly point of England, the few trees that rise up here and there are stunted and poor, while the hedges disappear and are replaced by fences formed of blocks of granite standing on end.

It took John Trevan two full hours to drive to the cottage where great-uncle Thomas and his wife lived during the spring, summer, and autumn. In winter they were glad to go and stay with their daughter, who resided at Sennen, a little village one mile distant.

The cart was left at the Land's End Inn, and its occupants walked towards the cottage which was a few hundred yards off. It was a simple building, and stood quite alone on a grassy slope facing the sea, no habitation but the small hotel being in sight. A board nailed on the outside wall announced "the first and last refreshment-room in England," kept by Thomas and Molly Nance. The old couple gathered many shillings during the season by providing accommodation for those visitors who preferred bringing their own provisions and being supplied with crockery, or who required boiling water for a tea-drinking. A case of minerals stood outside the door, and the sale of them was another source of income.

They were awaiting the arrival of their relations. Dorothy and Judith bounded on in front for the first kisses: Captain Nance, with his son-in-law and daughter, came more slowly.

Seldom have two finer old men been seen than were William Nance and his brother Thomas. The latter was in his eighty-eighth year.

"Welcome here once more, William," said Thomas Nance. "Thank God for sparing us to meet again."

"Yes, brother, I do thank God with you, for his tender mercies. He's upheld us through the battles and breezes of life for the greater part of a century."

They entered the cottage, which only consisted of two rooms. One of them was usually kept for visitors, but no strangers were to be admitted that day, and it being early in the season, there was little fear of any excursionist wishing to disturb the family gathering.

The morning was exquisitely fine and clear, but the wind was high, and the waves were scattering their white foam over the cliffs.

"Shall we go on to the Land's End at once to sing our hymn?" asked Thomas Nance.

"Yes," replied his brother, "we must keep to the old rule."

THE LAND'S END.

It is said that when Wesley stood on the Land's End for the first time, he was deeply impressed with the sublimity of the scene, and exclaimed:

"Lo! on a narrow neck of land,

'Twixt two unbounded seas I stand,

Secure, insensible:

A point of time, a moment's space,

Removes me to that heavenly place,

Or shuts me up in hell."

It was the hymn which contains these words the brothers sang at their annual meeting.

"Come, children, we will go first," said John Trevan.

They took the narrow path leading over the cliff to the granite rocks that form the Land's End promontory, and rise up out of the sea some sixty feet high; and standing close together on the point known as "Wesley's spot," sang the beautiful hymn which commences thus: "Thou God of glorious majesty."

When the last notes died away, the brothers walked together in silence towards the cottage; Mrs. Trevan followed with Aunt Molly, but John and his children lingered behind to admire and enjoy the magnificent scene. Judith clung close to her father, she was afraid of looking down into the deep sea or scrambling over the rocks without holding him firmly by the hand. Dorothy had no such fear, but watched the dashing waves with delight, and made her way alone through the narrow opening which leads to the extreme point of the Land's End.

They found a seat on a flat stone sheltered from the wind by a high rock; here they sat down and looked out on the broad Atlantic. The line of coast ends with Cape Cornwall, Longship's Lighthouse rises from a cluster of rocks about a mile from the shore, while about eight miles distant a dangerous rock of green-stone, called the Wolf, stands boldly up. A lighthouse has been built upon it within the last few years; but in the days of which we write, it had no such beacon to mark it, yet it was viewed with such alarm by mariners that many contrivances were thought of. One of them was to fix the figure of an enormous wolf on the rock, which was to be hollow inside, ad that the wind would make a loud noise in passing through, and ring the bells that were attached to it; but the tides were so strong, and the waves dashed over the rock with such violence, that this proposal was never carried out.

The rock on which Longship's Lighthouse is built is called Carn-Brâs. Including the rock, it is about one hundred and twenty-seven feet high. The walls are four feet thick at the base, and two feet seven inches at the top. During winter, when the weather is stormy, the tide rushes furiously against the rock, and renders landing so difficult, that the men in charge have to keep a large stock of provisions by them in case of a gale blowing for some days.

"How many people are there at Longship's, father, to take care of it?" asked Dorothy.

"Three, my dear. For a long time there were only two; but once a poor fellow in charge was cleaning some fish and fell over a rock. He was dead before his companion discovered him, probably he was killed on the spot. The living man managed to drag the body within shelter of the lighthouse, and then he showed a signal of distress; but though the people at St. Just saw it, they couldn't send help, for a sudden wind sprang up and a heavy storm raged for several days. Since this terrible event the change has been made."

"How dreadful for the poor man to be shut away from everybody, with only his dead friend near," said Judith, drawing closer to her father. "I hope he loved God, so that he could talk to him. How glad I am you don't take care of a lighthouse! I shouldn't like you to live nearly alone on a rock, and only come home sometimes."

"If we might be with father, I should like it very much," exclaimed Dorothy, "I'm so fond of seeing the waves beat up high; and if we lived at Longship's, Judith, we should see the seals asleep on the rocks."

"Not many of them, my dear," said John Trevan, laughing. "You must have picked that up in a school-book. It's a rare thing to see even one seal in our day. I remember coming across one on this coast, it was about six feet long, and had short bristly hair. It used to be said that seals defended themselves by throwing stones backwards at any one who came near them."

"That isn't true, father," said Dorothy.

"No, my dear, I never heard of seals having hands, though they have five toes on each paw. It's a Cornish story. We deal in all kinds of wonders here. Remember Jack the Giant-killer was born near to the Land's End."

"Oh, do let us hear about him, father. We are in the very best place to listen to stories of giants and fairies," pleaded Dorothy.

"Not to-day, for it's time to go in to dinner; but I will promise to take you to St. Michael's Mount soon, And then young Dick Nelson will amuse you, for he knows the history of every giant in Cornwall."

"That will be better than your telling us, father, for we shall get another holiday," cried Dorothy, clapping her hands with delight. "I do so like to go in a boat. We shall row across to the Mount, Judith."

"But you'll be sure to choose a fine day, father," said Judith; "I like being on the water very well if it's smooth, but I'm so frightened if the boat is tossed about."

"You may trust me, little one. But a fisherman's daughter should not fear even if the wind blows and the waves beat high. Now let us be moving, for I do not wish your mother or either of the old folks to have the trouble of coming to call us in."

Dinner was just ready when Mr. Trevan and his daughters entered the cottage, and the little party were very soon cosily sitting at the round table eating heartily, for the long drive and cold wind had given them good appetites. The conger pie was pronounced excellent, so were the pasties and other delicacies provided by Mrs. Trevan.

Some time after dinner was spent in talking over old times. Each of the elders of the party had much to say of God's merciful kindness. Then Aunt Molly proposed a walk to the Armed Knight and the Giant's Rock. The children were glad to accompany Aunt Molly, and their father and mother joined them, but the brothers remained in the cottage.

The Armed Knight is a fine rock which resembles a man in armour. The face is seen in profile, and the granite is joined so regularly as to look like a coat of mail. The Giant's Rock is a little farther inland, and consists of enormous stone boulders eighteen feet long. On the top of it are three rock basins. One is said to have been the giant's chair; a smaller stone near goes by the name of his ladle; and another is called his bed. Fable says that a gigantic race of men once inhabited Cornwall, who were supposed to amuse themselves by playing with great boulders of granite. They were said to laugh so loud as to shake the cliffs asunder; and, if they quarrelled, they fought so fiercely that the ground was strewn with the rocks they hurled at one another.

Of course these old stories and legends gave Dorothy and Judith great pleasure, and Aunt Molly was so full of anecdote about the giants that Mr. Trevan was obliged to remind his children that his day's work was only beginning when he reached home.

The farewell between the brothers was a touching one. Uncle Thomas never journeyed so far as Newlyn, and Captain Nance only visited the Land's End once a year; so that when they took leave of each other, they felt it might be the last parting on earth.

"Good-bye," said Thomas Nance; "may God keep you, brother William."

————————

GRANDFATHER'S TALES.

NOTWITHSTANDING Dorothy's efforts to be good-tempered and industrious, she did not always succeed. Sometimes she grieved her mother by her idleness and misbehaviour. The day after the delightful trip, described in our last chapter, was one of her bad times. Everything seemed to go wrong at school: her copy was smeared, her sums wouldn't come right, and after being kept in for some hours by the teacher as a punishment, she returned home in disgrace.

When she had been led to see and confess her fault, she said in a pitiful tone, "Oh, dear! How hard it is to be good. I mean to do better, but I often get tired of trying, and then I give it up. What shall I do?"

"Pray to God," replied her mother, "He will help you."

"Yes," added Captain Nance, "but you must set yourself to work to overcome your difficulty as well. You must both pray and strive. No one knows what they can do till they set about it with all their heart. Did you ever hear of Daniel Gumb, whom the Cornish people call the Mountain Philosopher?"

The children said that they had heard something about him, but begged their grandfather to tell them his history. This he proceeded to do.

GRANDFATHER'S TALES.

"In the church-town of Lezant, during the early part of the last century, there lived a poor stone-cutter, of the name of Gumb. He was a married man, with a large family of children. The eldest, a boy, was named Daniel, who from a very early age showed great fondness for study; and though he followed his father's trade, he was delighted when the day's work was done, so that he might eagerly study such books as came within his reach. As he grew older, he directed his studies to mathematics and astronomy. When Daniel Gumb grew into man's estate, he married, and settled in a little cottage not far from his father; and now it was necessary for him to work diligently in order to maintain his wife. He was very industrious, only sometimes mapping stars on the granite which he was cutting, instead of hewing the big blocks into shape for building.

"He made but little progress in his studies, as his family cares increased, for he had several young ones to feed and clothe, thus he had no spare time to devote to working out problems. He began stone-cutting early in the morning, and did not leave off until late at night; but yet he earned barely enough to keep his wife and children in the same degree of comfort that his fellow-workmen kept their wives and children. One thought oppressed him, which may be stated in these words:

"'I am wasting my time and energies on stone-cutting, when I am desirous to learn. How can I alter this state of things, and make more leisure to pursue my studies?'

"At last he devised a plan. It cost money to maintain his present position, why should he not seek for some cave where he might live rent free, and have no taxes to pay?

"Not very far from Lezant stands Cheesewring, so called, it is supposed, because it resembles a cheese-press."

"Do you mean that it's small at the bottom and large at the top, like a wring they use when they make cider?" interrupted Dorothy.

"Yes, my dear. The rocks which form Cheesewring are seven in number, and stand one on the top the other. The lowest three are only six feet in diameter, while the upper four vary from ten to twelve feet; and they look so carelessly heaped up, that when I walked underneath them, I had a sort of fear lest the top boulders would fall and crush me."

"Please, before you go on, tell me what is the meaning of the word diameter," said Judith.

"The width of anything, right through its centre. You will better understand the shape of Cheesewring if you think of the enormous top-heavy toadstool we found in the fields a few mornings ago. It had a slender stalk, and such a large thick umbrella-shaped top, that we wondered how it was held up by what appeared a thread in proportion. I was quite a boy when I first saw Cheesewring, and I thought the great rocks at the top could be pushed over easily. But children, they've stood for hundreds of years; those heavy boulders, which look ready to fall, are so evenly balanced on the small ones below, that many sticks, nay, iron crowbars, and an army of men would be needed to turn over the tons and tons of stone."

"How came they to be so queerly put up?" asked Judith.

"Some say the old Druids had a hand in it, and that they used to worship them. I don't know how far this is true; but one thing is certain, Cornwall has no more remarkable objects than Cheesewring and the Hurlers, which lie near to the former. But to continue my story: Daniel Gumb decided that the hill on which Cheesewring stands, was the place where he was most likely to find his future home. Masses of granite were heaped up irregularly in every direction, and he felt sure he would soon be able to fix on a spot which would serve his purpose. At last he found several rocks which were clustered so close together as to form a rough kind of cavern, and this he determined to make fit for habitation. First, he widened the opening, then he enlarged the inside, and propped up an enormous slab, which formed the roof. When this was completed, he made a bedroom for himself out of a rock that was situated a little above; it was by no means a large room, in fact, only sufficiently spacious for him to squeeze his body into. On this rock he scratched the date of the year 1735.

"So soon as he had completed his work, he returned to Lezant to bring his wife and family to their new home. We have but little record of Mrs. Gumb, beyond knowing that she followed her husband's fortunes, and removed to the cave with her family, where she remained until her death.

"Daniel became a much happier man after this, for he had no longer to keep pace with his fellow-workmen. He only wanted just money enough to maintain his wife and children from actual want. The roughest clothes sufficed; the furniture might wear out and break, it would need no replacing; the landlord would not come for his rent, nor the tax-gatherer for his taxes; there were no glass windows to smash; there was nothing in this half-savage rough life which required him to devote every hour of the day to stone-cutting, in order to make money. He could shorten his hours of work, and lengthen his hours of study.

"Society fled from him. His former friends deemed him mad, and his relations avoided him. Strangers only visited the recluse and his family, in order to assure themselves that the story their landlady had told them about Daniel Gumb was no fiction. But what cared the mountain philosopher for the world's opinion, or his relations, or his friends. He could map out the stars, and solve difficult problems at will; he was his own master, and beyond the pale of society. Just try and realise the facts of this strange history for yourselves, my dears. Here was the love of study absorbing every other thought, and making a man throw up an honest position among his fellow-countrymen, in order to store his mind with knowledge."

"But it was not quite right," exclaimed Judith. "I think it was selfish of him to take his poor wife and children away from their home, and make them live in a cave."

Captain Nance looked up and smiled at his little granddaughter. "You've hit the right nail in that remark of yours, Judith," he said. "I agree with you; there is something very selfish in Daniel Gumb's conduct. Only picture his poor wife exposed to the storm and cold of winter, with her young children, and only granite blocks to screen them. I remember that when I was young I thought him quite a hero and martyr, but not now. I've lived beyond that. He would have fulfilled God's purpose in creating him, so far as I can judge, if he had conquered his longing for study, because he had dear ones who depended on him for support. He need not have given up all his learning, but he might have carried it on as recreation. I think he must have had many sad thoughts and many misgivings, when his children fell ill and had so few comforts around them. What availed his problems, or his star-mapping then? Could they furnish meat and drink for his sick and suffering little ones?"

"Did any of his children die in the cave?" asked Dorothy.

"Yes," replied the old man. "Some were born, and two died there. Don't mistake my meaning, children, when I speak thus. I honour Daniel Gumb in one sense; I condemn him in another."

"You said something about Hurlers," remarked Dorothy, "I can't think what they are, and yet I've a sort of remembrance you told us a story about them. Please tell it again."

"Dorothy, Dorothy, you're always after old traditions," said John Trevan. "Certainly that which relates to the Hurlers is as strange as any in our county. They are said to have been Cornish men who came out one Sunday, and amused themselves by hurling balls about, and because they broke God's day they were changed into pillars of stone."

"That tradition teaches us a good lesson," replied Captain Nance. "We all need to value our Sabbath privileges more than we do; but, alas, how many people there are in our world who are not thankful for the rest to the body and refreshment to the soul that the one day in seven brings."

"Very true," answered John Trevan, rising from his chair. "I must be off now, for my spare time is gone. I've just a few more words to say to Dorothy. You will not easily forget the sorrow you've brought on yourself, and all of us to-day, my darling, by your naughtiness; and now I am going to prove how entirely I forgive you, by taking my little girl and her sister to St. Michael's Mount to-morrow, if the sun shines. The day after to-morrow you can show you are in earnest about wishing to do better, by being very attentive at school."

"Oh, thank you, thank you, father, I will, indeed, I will try hard to have my lesson right the first time."

"Very well, I believe you. Now, children, you may come with me down to the boat if you like."

Dorothy and Judith gladly accompanied their father, and waited on the shore until he rowed out to the "Mary Ann," which was anchored in the bay. They left the sands then, and walked into New Street, where they watched him until the sails were set, and he was some distance off.

"Judith, how happy I am," said Dorothy, as they returned home; "I will pray to be good if you will help me."

"Yes, indeed I will, Dorothy," answered her sister, affectionately, "we will help one another, for I want help from you just as much as you want help from me; and we both need to be helped by our Father in Heaven."

Captain Nance had just lighted his pipe when his grandchildren entered the room.

"Grandfather," said Dorothy, "let us talk together; there is some time before we go to bed."

"What shall we talk about?" asked the old man.

"Anything you like. Or will you tell us of something that happened when you were a boy; or about any of your friends; or what is the very best of all, a grand story of a shipwreck, that you saw?"

"Then you can bear a sad one, for I'm not much inclined to make you laugh this evening. It's curious that I've been thinking while you have been away of that shipwreck which happened off the Brisons nine years ago. You can't understand, now, my little girls, how an old man lives in the past; young folks dream of the future, and build their castles; old folks build no castles, but turn over and over again in their mind the events which befell them long ago, perhaps in the prime of youth, or it may be in early manhood. Yet I'm wrong when I say old folks build no castles, for I dream of one; a beautiful and stately mansion which hath a sure foundation, its builder and maker is God. I am not afraid that it will crumble and decay, for—

"'I know whom I have believed, and am persuaded that He is able to keep

that which I have committed unto Him against that day.'

"It's plain sailing, Dorothy, to that mansion. Yes, plain sailing so far as God has revealed His will to us in His holy word, and by the teaching of His Spirit. It's we who are to blame when we think we know better than our Almighty Friend, Father, and King."

Captain Nance continued to puff the smoke from his pipe, but he made no further remark, and some minutes elapsed before Dorothy ventured to say,—

"Please, grandfather, tell us about the shipwreck."

"Yes, that I will. I'm glad you brought me back again, for my thoughts were far away. When I was captain, I steered as directly as I could to the harbour I had to reach; and now I'm steering just as straight for Heaven; that's my point, the harbour of refuge in the land of Canaan. But I mustn't ramble from one thing to another, I'll try and keep to my subject and tell you about the shipwreck:—

"In the second week of January, 1851, business took me to your great-uncle Thomas at Sennen. On the following day he accompanied me to St. Just on the same business. Eleven years ago I could manage the journey to the Land's End without much difficulty, but now, as you know, I soon get weary, and when I bid farewell to my brother, I think sailing orders will come for him or for me before we meet again. You have seen Cape Cornwall from the Land's End, and know that it is only one mile from St. Just. To the left of the Cape lie the Great and Little Brisons, or Sisters: they are very dangerous rocks, some sixty or seventy feet high.

"It was on the morning of the 11th of January that brother Thomas and I went to St. Just; it had been blowing a strong sou'wester all night, and the waves dashed on to the shore mountains high. At daybreak a brig from Liverpool, which was bound to the Spanish Main, struck upon a reef of rocks between the Great and Little Brisons, and was dashed in pieces. The crew, which consisted of nine men, and one woman, succeeded in scrambling on to a ledge, where they would have probably been in safety had the tide been going out; but it was coming in, and every moment their position was more terrible. Ah! Children, we on land, and clear of danger, talk about being prepared; but face to face with eternity, words are tested, and we are proved as to whether our faith be firmly anchored in Christ.

"They stood huddled closely together, trembling and waiting, knowing the tide came nearer every moment, and that the first strong wave would cover them. It came only too soon, and ten living people were swept into deep water. Seven sank to rise no more, and three were brought to land. But how? First, I will tell you of the one whose life I had no hand in preserving, and then pass on to the two whom I helped to save. He was a mulatto, a dark skinned man, who was a good swimmer, and he managed to grasp a part of the floating wreck on which he scrambled, and by using a bit of canvas for a sail, and a plank as a paddle, kept himself floating on the water until he was rescued by fishermen from Sennen.

"Brother Thomas and I reached it just when the excitement was at its highest. The people were standing about in knots talking. We soon learned the reason.

"I at once said to my brother, 'I am off to the coast-guard station; it is an old tar's proper place.'

"By the aid of the glass I saw a man and woman, who turned out to be the master mariner and his wife, standing on the Little Brison. They had been washed on to this rock and managed to keep their footing, for they had crawled high enough to be out of the reach of the waves.

"'Can we save them?' 'Can a boat live in such a storm as this?' 'Who will venture out?' 'It's madness to try!' were some of the remarks we exchanged, as we stood with the crowd which gathered to watch the two figures on the Little Brison.

"We had just decided to man a boat, when we saw the 'Sylvia,' one of Her Majesty's cutters, ploughing her way round the Land's End. At last she lowered her boat, and made a desperate attempt to reach the husband and wife. Again, and again, and yet again, the brave fellows tried to near the Little Brison, but they failed, the sea was too tremendous for their efforts to be successful.

"Thus the afternoon closed, and as daylight faded, we saw the outline of the two forms standing motionless—for so they appeared to us—on the rock. It was a terrible picture. Brother Thomas had gone home. As soon as he had transacted his business, he came to me to ask what I intended to do.

"'I cannot leave this spot,' I answered.

"So I remained at the coast-guard station, for the men there were not strangers to me, and even if they had been, we were drawn together by a common sympathy. I should have been untrue to my sailor's colours had I returned without trying to help these poor creatures.

"'I am ready to go in the first boat that is sent off,' I said to the superintendent.

"I spent the hours of the night in prayer. I cried to my Lord to interpose and save them. My heart went out in supplication on their behalf. The Apostle Peter did not cry out more earnestly, 'Save, Lord, or I perish,' than I did for the lives of those two strangers.

"When daylight broke, I strained my eyes through the glass, and by degrees recognised the two forms; but no longer standing upright. They had cowered down, and but for an uplifted hand every now and then they gave no signs of life.

"'Help us to save them, Lord,' I cried, when I caught sight of them first. 'We cannot stem the fierceness of the storm; we cannot make the waves obey by saying, "Peace, be still!" but Thou canst be merciful to us all, and come and save.'

"The violence of the sea was gradually abating; and I thought it grew even quieter after my prayer. Directly it was sufficiently light for us to dare to venture, the superintendent of the station ordered a boat to be manned, and carrying several rockets with him, he was rowed out, accompanied by two other boats. I suppose you know that rockets are used to throw a line, and that they are generally sent off from the shore; but this was a peculiar case. I went in the second boat. We could not get within a hundred yards of the Little Brison, and from this point the first rocket was fired; it failed to reach the rock-bound prisoners. A second was fired with the same result, but the third brought the cord close to the man.

"We watched him breathlessly as he tied the cord round the woman's waist, but just as she plunged into the water, a terrific swell obliged us to look to ourselves. The line was secure, and in a few minutes the poor woman was drawn into the superintendent's boat. She still breathed, though only for a little while. Whilst in the boat, her spirit fled to another world. Yes, ere the second line was drawn in, which guided her husband to the boat in which I was, her sailing orders had come.

"It was a dreadful moment for all of us; it has left a deep mark behind. Come what will, that scene will never pass from my memory; but it will ever stand out vividly. Even now, as I talk, my pulse almost stands still, and I grow quite cold.

"We reached the shore with the living and the dead. The poor man was tended carefully, and gradually returned to consciousness and life; he mourned deeply for his wife; they had not been separated since their wedding day. She had borne the trials of a sailor's life, with her husband, and he felt so lonely without his dear one at his side to cheer him. For twenty years she had been his faithful partner."

"Did she love Jesus, grandfather?"

"Yes, Judith, she had served her Saviour from childhood; and what made the tie so strong between the husband and wife was that he owed his conversion, under God, to her. He told me that he was a scoffer when he married, but that her example had taught him to pray.

"The captain told us that as they stood in those terrible hours on the rock, she encouraged and comforted him by repeating these words many times:

"'Fear not, for I have redeemed thee; I have called thee by thy name;

thou art Mine . . . I am the Lord thy God, the Holy One of Israel, thy

Saviour . . . Since thou wast precious in My sight, thou hast been

honourable, and I have loved thee.'

"'These promises stand as fast now as when they were written,' she cried; 'He loves us as we stand here helpless and defenceless. Do not let us forget that, but believe that though He appears to hold out no hand to save, He does not leave us nor forsake us.'

"It was astonishing, he said, to see the calm manner in which she spoke. Both grew quiet and trustful at last, and seemed to hear a still small voice speaking out of the storm, and saying, 'Peace, be still!'

"I could have told him that I, too, had heard that voice when I was passing through deep waters; but it wasn't the right time for me to speak of my sorrows; it would have been selfish, children, to intrude them on him when he was smarting so bitterly under his own heavy cross."

Dorothy and Judith had listened to this story which was filled with so much sadness several times before: their grandfather had not told it to them so often as many others, for their mother was too pained to hear it; it seemed in her own mind to be connected with Willy; he might have been shipwrecked with no one near to save! But Mrs. Trevan had walked to Penzance directly after her husband left home, and now returned with a well-filled basket.

"What is the matter?" she asked, noticing the serious faces of the three.

"It's nothing of consequence, Philippa," answered Captain Nance. "I've been telling them something of the past, that's all, and I'm in a serious mood to-night, so I've been speaking of sad things. Let us forget them and hear what you've been doing; if I may judge from the number of parcels in your basket, you have been spending your money freely, and marketing for the week."

"You are right, father," answered Mrs. Trevan. "Tea, sugar, pepper, salt, and many other small articles were wanted. Come, children, and help me to put them away in their proper places."

————————

ST. MICHAEL'S MOUNT.

EARLY next morning Dorothy and Judith were down on the sands awaiting the arrival of their father. The boats were coming in fast, and before long the "Mary Ann" anchored in the bay, and the crew rowed to land with a large supply of mackerel.

"I shall be ready to start for St. Michael's directly I've looked to the nets," said John Trevan to his little girls.

It is curious to see with what method the Newlyn fishermen put their nets out to dry. They pile them upon one of their comrades' shoulders until the wonder is he can walk at all under such a heavy load. The burden being taken off with the same precision as it is put on, the nets come off in perfect order and hang over the iron railing, or lie along the sands and shingle.

"Dorothy," said Judith, as they stood watching the process, "I'm glad we live by the sea, and that father is a fisherman."

"Why?" asked Dorothy.

"Because I seem to feel the life that the Lord Jesus lived with his disciples so real. We read in the New Testament so much about nets and fishermen, and they did just the same in those days as now."

"So they did. I never thought of that before."

"I have many times. I like to picture to myself the Lord Jesus standing on the shore, or sitting in a boat preaching; and how surprised Simon, and Andrew, and James, and John must have been when they were called by him and told they must be fishers of men. They were doing exactly what father does; two were casting their nets into the sea, and two were mending their nets."

"I'm just ready, children," called John Trevan. "Run to the boat. I shall follow you in a moment."

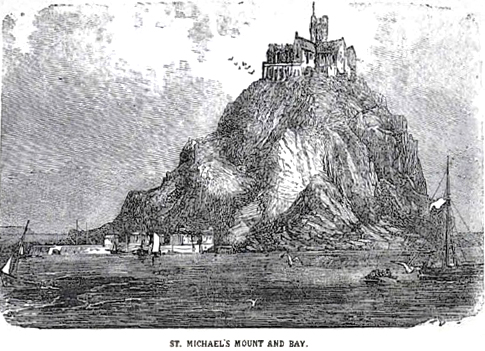

St. Michael's is the principal feature of Mount's Bay. As seen from the shore it appears like a lofty island rock rising up out of the sea, with a large castle on its summit. When the tide is at its lowest, the island is connected with the mainland by a causeway of rocks four hundred yards long, by which means you reach the old town of Marazion; the rest of the day it can only be approached by boat.

It boasts great antiquity. Here it is said the Phoenicians came to buy tin three thousand years ago, when it was inhabited by traders who were glad to give this metal in exchange for salt, bronze vessels, earthenware, and other commodities. In the beginning of the Christian era, the dwellers on St. Michael's Mount are described by Roman historians as being civilised people who traded largely with foreign countries. In later times a Benedictine monastery was reared on the Mount, and the fame of St. Michael the Archangel, who is described in an old legend as appearing to some hermits upon one of its crags, drew many pilgrims from all parts of Britain. Nuns, monks, and soldiers, occupied the island at intervals until the seventeenth century, when the monastery was turned into a castle, and Charles I. sojourned there for a brief space to encourage the sturdy miners of Cornwall to aid him in the fight against Cromwell. About the year 1660 the island was sold to the St. Aubyns, and remains in the possession of that family to the present day.

ST. MICHAEL'S MOUNT AND BAY.

The bay was calm enough to satisfy even Judith. There was not a cloud to be seen in the blue sky, and the bright sunlight lit up the pretty town of Penzance with its curving shore and background of hills, the old town of Marazion, Cuddan Point, and far away to the Lizard.

There is a little fishing village at the foot of the Mount, and thither John Trevan was bound, for he was anxious to consult his friend Richard Nelson about some matter connected with herring fishing, which begins after the mackerel season is over. He pulled straight to the stone steps in the harbour, and saw to his satisfaction that the very man he wanted was standing on the pier talking to a comrade.

After the bustle of landing was over, and the first greetings had been exchanged, Mr. Trevan asked: "Is Dick at home? My girls want a run with him over the Mount."

"He is here to answer for himself," said his father as a handsome boy of fifteen joined them, and shook hands warmly with Dorothy and Judith, who were old friends of his.

"How jolly to see you," he exclaimed. "You couldn't have come a better day. I'm going to be at home."

"Take the lassies to your mother," said Mr. Nelson, "and ask her to have some dinner ready for us at one o'clock."

The village at the base of St. Michael's Mount is surrounded on the land side by a wall of granite; a gate at one end admits its inhabitants and visitors to the Mount. The fishermen lay their nets out to dry on, the sloping turf just without the wall, and a little farther up is the well which supplies the villagers with fresh water. Most of the cottages look over the bay, but a few face the Mount, and it was to one of these Dick led the way. He stopped at a pretty little house, with a tiny garden at its side, and a fine old myrtle tree climbing up its walls and peeping into the gabled windows. A good-looking woman was standing outside-washing clothes in a large tub. She was delighted to see the little girls, and dried her hands hastily before she kissed them.

"How did you come, my dears?" she asked.

"Father brought us," said Dorothy. "He wanted to see Mr. Nelson, and gave us the treat."

"You must stay and have some dinner," said Mrs. Nelson.

"Yes, mother, they're going to stay," replied Dick. "Father says he'll be in at one. We're going up the Mount now."

"That suits me exactly, for in a couple of hours I shall have cleared up and be quite ready for you."

The ascent to the old castle is an easy one. The rock on which it is built is about two hundred feet high, and on the east and west sides of the cliff terminates abruptly, and the shore can only be reached by a flight of steps cut in the stone.

"Can we go inside the castle to-day?" asked Dorothy. "We've never seen the rooms, though we've been up here so many times. Mother said we might go in, if you can manage for us; she's given me some money for the housekeeper."

"All right," answered Dick.

They mounted the stone steps and rang the bell, which was answered by a respectable woman who permitted them to enter, and pointed out the various objects of interest.

The hall, which was the refectory of the monks, and the Benedictine chapel, claims the most notice; but that which had the greatest charm for the children, was a vault discovered some years ago when the chapel was undergoing repairs, in which the bones of a full-grown man were discovered. It is supposed that he was bricked up there and left to die. Dick and Dorothy entered the vault, but Judith was too timid to accompany them. Dorothy would also have liked to go to the top of the church tower and sit in what is popularly called St. Michael's chair, but the wind was so high the housekeeper would not permit it.

"There's plenty of time before you," she said good-humouredly to Dorothy. "You may have another ten years on your shoulders before you need climb to St. Michael's chair; it's not for such as you, but young brides, or old ones for that matter, who are disappointed if they don't sit in the chair before their husbands."

"But why?" asked Judith.

"You surely know," said Dick. "Every one in Cornwall has heard of St. Michael's chair."

"Indeed, we never have," replied Dorothy; "do tell us about it. I only know that St. Michael's chair is in the church tower, but not why it is called so."

"Because the wife is said to be the master if she sits in the chair before her husband; so you see, my dear, you may wait many years before you need to mount into the tower," said the housekeeper.

"I learnt the story about St. Michael's chair at school in a piece of poetry," said Dick. "I can't think how it is you've never heard of it. It begins like this:—

"'Merrily, merrily rung the bells,

The bells of St. Michael's tower,

When Richard Penlake, and Rebecca his wife,

Arrived at St. Michael's door.

"'Up to the tower Rebecca ran,

Round, and round, and round;

'Twas a giddy sight to stand a-top,

And look upon the ground.'"

"And did she sit in the chair?" asked Judith.

"Yes, but the bells rang so loudly, that the chair rocked, and out she fell."

"Is it a real chair?" questioned Dorothy.

"No, my dear; only a stone, and by no means a comfortable one to sit on; and why it is supposed to be endowed with such gifts it is hard to say," replied the housekeeper.

The young people thanked her for her kindness, as they left the castle. They rambled about for some time and gathered flowers, then they watched the rabbits skipping and running hither and thither among the furze. At last Dick suggested that they should go down the steps to a sheltered place, where they could sit and talk.

"Yes, do," said Dorothy; "for we want to hear from you the story of 'Jack the Giant-killer.'"

"Who told you that I knew it?"

"Father. Now begin at once, Dick."

"I will directly we've found a comfortable rock. I think I'd better take you to my summer-house."

They had to scramble over many, large boulders, until they reached one which was sheltered by a higher rock behind it; this Dick called his summer-house. It was close to the shore, and a warm snug place to sit in.

"Before I begin my story I must ask you one question, and I wish Judith to answer it," said Dick. "Do you believe that Jack the Giant-killer was a real man?"

"No, of course, not," she answered. "It's only one of the old Cornish tales with no truth in it."

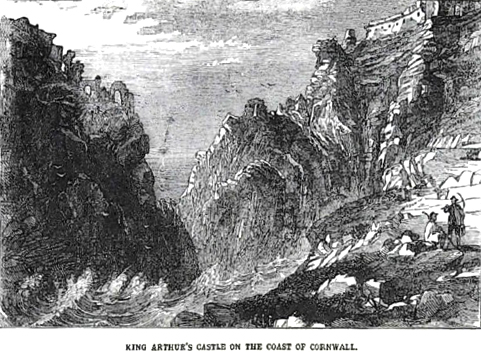

KING ARTHUR'S CASTLE ON THE COAST OF CORNWALL.

"Very well, as that's settled, I'm ready to tell you all I know about him. Many years ago a giant inhabited the Mount, who was named Cormoran. He was eighteen feet high, three yards round, and a very fierce-looking fellow. He lived quite alone, and allowed no one to come near him. When he felt hungry, he waded through the water on to the shore, and went to one of the villages to steal cattle. He was so strong that he could carry six cows on his back at once, and a large sheep between his finger and thumb. Of course, all the people round very much disliked this giant, and felt it was hard to lose their cattle; but yet they were too much frightened of him to venture to show fight when he appeared.

"Near to the Land's End lived a rich farmer, who had one son, called Jack, and he determined to win a name for himself by getting rid of Cormoran. He thought for many days and weeks before he could make up his mind what to do, and in that time he tried his hand on Thunderbore, a huge fellow, with flaming eyes and long hair, that hung over his shoulders like curled snakes. He succeeded in killing this giant, who lived very near to his father's farm, though the books don't say how he managed it, but perhaps in the same way that he killed Cormoran.

"At any rate, soon after the death of Thunderbore, Master Jack determined to dig a pit on the spot where the giant always set his foot when he landed. He covered it with a stone, which he poised so cleverly that it only required a little touch to make it fall into the deep hole. The plan succeeded perfectly. Cormoran came out of his cave one day to seek for provisions. He waded through the sea, and set his foot on the stone: it gave way, and he fell in, and was so hurt that he lay moaning until he died. Of course Jack became a great man, and he killed a good many more Cornish giants. So ends my story. Now, Judith, tell me what you have been thinking about, for you've been looking a deal too grave."

"Just this, Dick," answered the little girl. "You know the Bible contains a story about a giant, and a boy who killed him, and I thought how grand it was compared to yours; and it's all true, too, every word of it."

"Tell it to me, and then I'll give you my opinion," said Dick.

Judith hesitated for a moment, and whispered to her sister.

"Oh, yes, do," answered Dorothy aloud. "Dick," she added, "Judith wrote a history of David and Goliath for teacher, only last Sunday, and she's got it with her."

JUDITH READS HER STORY OF THE GIANT.

"That's capital; let me hear it."

"It isn't quite all my own," said truthful Judith; "teacher altered one or two things—not many. I wasn't allowed to look at my Bible after I began to write, but I read the history over a great many times so that I might remember it."

"And she had a prize because it was done the best in the class," exclaimed Dorothy.

"That's first-rate," cried Dick. "Don't lose any time, Judith."

The little girl took a roll of paper out of her pocket, and read thus:

"In the days of King Saul, the Israelites fought against the Philistines, and both armies drew up ready for battle one day. The Philistines had a great giant on their side, called Goliath of Gath, who was about eleven feet high, and wore a helmet of brass on his head. He was armed with a coat of mail; the staff of his spear was like a weaver's beam; and he had a man going before him to carry his shield.

"He stood and cried to the armies of Israel, and said, 'Why are ye come out to set your battle in array. Am not I a Philistine, and ye servants of Israel? Choose you a man for you, and let him come down to me. If he be able to fight with me, then we will be your servants; but if I kill him, then shall ye be our servants, and serve us. I defy the armies of Israel this day.'

"King Saul and all Israel were frightened when they heard these words, for they had no one who dare meet this giant in single combat. For forty days he came and presented himself before them, and they grew more and more afraid.

"In Bethlehem Judah there lived a man named Jesse, who had eight sons. The three eldest followed King Saul to battle, and the youngest fed his father's sheep. He was called David, and had a beautiful countenance; and God loved him, and was with him. One morning his father sent him to the camp with some corn for his brethren, and ten cheeses for the captain of their thousand.

"David found the two armies drawn up ready for battle, so he ran into the midst of the Israelites and talked to his brothers. While he was hearing how they fared, the great giant came out and spoke the same words, which frightened the men of Israel so much that they fled away from him.

"David saw all this, and asked the men who stood near him, what should be done to the one who killed the Philistine, and took away the reproach from Israel?

"'The king will make him very rich,' they replied, 'and give him his daughter, and make his father's house free in Israel.'

"When Eliab, David's eldest brother, heard him ask this question he was very angry, and said, 'Why didst thou come here? who has charge of thy sheep? Thou hast only come to see the battle.'

"But David answered, 'There is a reason for my coming.' So he turned from his brother and asked another, 'Who is this Philistine, that he should defy the armies of the living God?' Again he received the same answer; and the people went and told Saul his words.

"The king sent immediately for David. The young man entered into his presence, and said boldly, 'Let no man's heart fail because of this giant; thy servant will go and fight with this Philistine.'

"To this the king answered, 'Thou art not able to fight with him, for thou art a youth.'

"Then David told Saul that a lion and bear had come one day and taken away a lamb out of his flock, and that he went after them, and slew them. And he said that he was not afraid of the great giant, who had defied the armies of the living God, for the Lord would deliver him into his hand.

"When Saul heard these words, he answered, 'Go, and the Lord be with thee.' The king clothed David in armour, but the latter said, 'I cannot go with these, for I have not proved them.' So he put them off, and took his staff in his hand, and went to the brook, where he chose five smooth stones, which he put into his shepherd's bag; and with his sling in his hand, he drew near the Philistine.

"As soon as Goliath looked on David, he scorned him, and asked, 'Am I a dog, that thou comest to me with stones? I will give thy flesh to the fowls of the air and the beast of the field.'

"David answered, Thou comest to me with a sword, and a spear, and a shield; but I come to thee in the name of the Lord of hosts, the God of the armies of Israel, whom thou hast defied. This day the Lord will deliver thee into my hand, and all the earth will know there is a God in Israel.' So Goliath came nearer, and David ran to meet him, and put his hand in his bag and took out a stone, and slung it, and smote the Philistine in his forehead, and he fell upon his face to the earth."

"Well done, Judith," said Dick. "I declare I couldn't do it so well, and I am two years older than you are."

"Which story do you like best, yours or mine?" asked Judith.

"Why, yours to be sure, because I know it's true. Besides, just think of the beautiful way in which it's written in the Bible. I never get tired of reading about David, and often envy him."

"Now let's settle why we should like to be David," said Dorothy. "Supposing you say first, Dick, as you are the oldest."

"Because," answered the boy, thinking for a moment, "because I should like to have been the one to kill the giant, when the whole army was afraid of him."

"And I," said Dorothy, "because I should like to have been as much thought of as David was, and get into the king's favour."

"And I," said Judith, speaking in a low voice, "because God was with him, and helped him to kill the giant."

"You've hit on the right reason, Judith," exclaimed Dick. "You always were good. I don't believe you've half the temptations to be naughty that Dorothy and I have."

"Oh! Don't say that. Nobody knows exactly what the other is like," replied Judith.

"That's true," answered Dick. "Still I can't help thinking you are very good, Judith. Now let us go back; I have to fetch mother some water before dinner."

John Trevan and his daughters returned to Newlyn early in the afternoon, for the former was too busy to be longer absent. The sea was a good deal rougher than when they were going, but not enough to make Judith nervous. She and Dorothy chattered to their father all the way home. They told him of their morning's conversation.

He agreed with Judith that a fisherman's life often reminded him of the Lord Jesus and His disciples.

"I think," he said, "that the time when the Master stood by the lake of Gennesaret, and the people pressed upon Him to hear, so that He was obliged to enter into a boat, is my favourite scene. If you remember, our Lord commanded Simon to thrust out a little from the land, and sat down and taught the people in the ship. And after He had done speaking, He ordered Simon to launch out into the deep, and let down his nets; and the disciples answered,—

"'Master, we have toiled all the night and have taken nothing:

nevertheless at Thy word I will let down the net.'

"And when they had done this, they enclosed a great multitude, and the net broke. How often I have pictured this to myself when we have been hauling in a great draught, or have toiled for hours and caught nothing."

Just as John Trevan finished speaking they came near enough to the shore for the rope to be thrown out. It was caught by one of the crew belonging to the "Mary Ann."

"We want your opinion, captain," he said.

"I'm here," answered John. "Go home, children, and do not wait for me."

Dorothy and Judith were soon sitting at their grandfather's side, giving him and their mother a full account of the day's proceedings. Among other things they spoke of St. Michael's chair, and said they wondered they had never heard it was so famous.

"Just as well not, little ones," said Captain Nance. "We've no bickering for mastery here. Your father and mother have each their own place to fill, and they seek help from One who is able to uphold their footsteps, and teach them how to govern themselves. That's the secret of true happiness in married life: After all, St. Michael's chair and the charm it is said to possess, is only one of the old Cornish traditions."

————————

WILLY'S BIRTHDAY.

DOROTHY won golden opinions from her parents and teacher next day. Her lessons were so well said, and her sums so correctly done, that Miss White sent a message home by Judith, expressing how satisfied she was with her pupil.

"You're very happy to-day, Dorothy," said her father; "I can see it in all your movement, and your face is beaming."

"Yes, father, I am very happy. I tried hard not to be idle this morning. I was just a tiny bit sorry that I had to go to school, but I asked God to help me to act properly, and Judith was so kind; and now I'm so glad to think that Miss White is satisfied to-day."

"You can't have a better helper than your Heavenly Father," said Captain Nance. "He'll bring you to the port at last. Don't forget what I told you about His being our guide. I've borne the battles and the breezes of life long enough to know where to find safe anchorage."

Dorothy not only merited her teacher's praise on that day, but on other days that followed. She tried to conquer herself, and succeeded as she had never done before, because she endeavoured to think of these words at all times,—

"Thou God seest me."

She told Judith she meant that verse to be her birthday text.

"And it shall be mine too," answered her sister.

The month of April wore away, and May set in. The hedges round Newlyn grew greener every day; the trees came out in full leaf, the ferns waved in wild luxuriance, and the banks were blue with hyacinths.

The mackerel season ends in the middle of May, and the fishermen employ the weeks that intervene before the pilchard season commences, by fishing for herrings off the coast of Ireland.

The "Mary Ann" left Newlyn late one afternoon in the third week of May.

"I shall think of you on Willy's birthday," John said to his wife, just before starting; "you'll bear up for my sake, Philippa?"

"I will try to," she answered; "but I must remember my boy as of old. Nine years, John, on the 8th of next month, since he left us. I think of him as a boy still, but if he's living he's a young man of twenty-four. How happy he would have made us had he turned out well; he would have helped you in so many ways."

"So he would, wife, and God only knows how gladly I should welcome him home. I'm always changing my opinion about him; sometimes I doubt much if we ever see him again in this world, and then again I feel sure he will return. God grant that we shall meet him in heaven, if we never see him here."

"Father is the only one who seems clear about his being alive, and coming home; and I find myself dwelling on the old man's words."

"Try not to, Philippa, it makes the uncertainty harder to bear. Leave the matter in the Lord's hands; and now let us join grandfather and the children."

When all was in readiness for departure, John bade adieu to his wife and daughters, who, with Captain Nance, accompanied him to the harbour. He shook hands with his father-in-law, and said, "God bless and keep you."