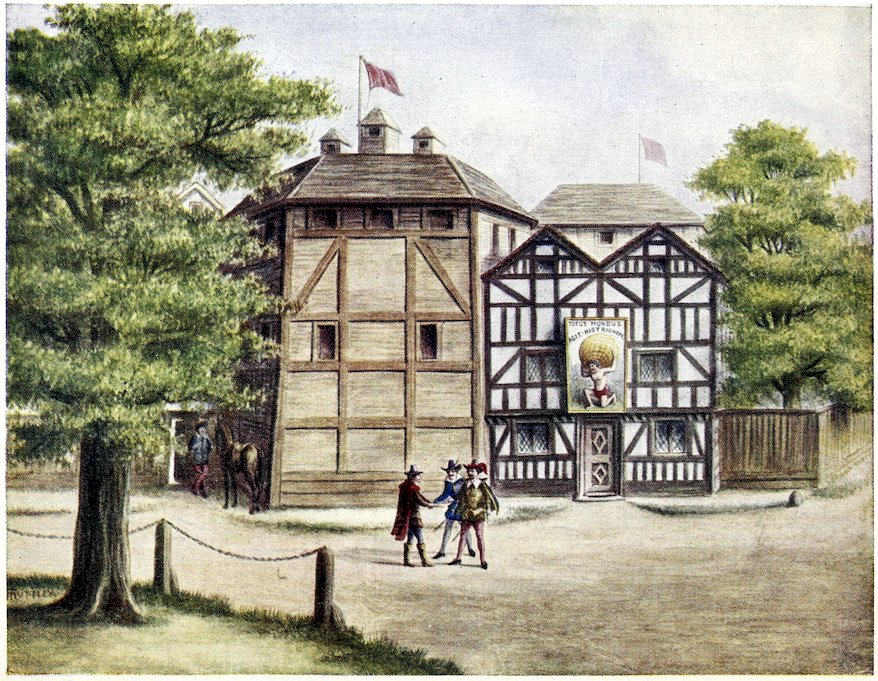

The Old Globe (or Atlas?) Theatre Bankside.

The Meeting of Shakespeare with the Burbages, Father and Son.

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

The Old Globe (or Atlas?) Theatre Bankside.

The Meeting of Shakespeare with the Burbages, Father and Son.

The idea of dramatic representation is to produce the impression of reality, and the value of such representation is in direct measure with the force of such impression. In this connection stage scenery and effects are of the utmost importance. When properly used, they add tremendously to the realism of dramatic representation. We see this clearly proved in London to-day at such theatres as Drury Lane and His Majesty’s. The success of the big productions at those theatres depends almost, if not quite, as much upon the quality of the scenery and effects as upon that of the plays performed or of the actors and actresses engaged. This is shown by the views expressed by the dramatic critics and the public generally. Perhaps the production at Drury Lane is a strong melodrama. What is most discussed in connection with that production? Almost always some big and novel effect, such as the representation of a race between aeroplanes or a battle between submarines. Again, in the case of a Shakespearean production at His Majesty’s, the talk in the green-rooms and at the dinner-tables of London is often more of the scenic beauty of the production than of the achievements of the actors and actresses, and the talk of the ‘man in the street’ follows the same lines.

2The ancient Greeks and Romans were very fond of the drama and have left us some great plays, but they did not realise the value of scenery; indeed, very often their performances were given without scenery of any sort. The drama of the Romans, like most other manifestations of their civilisation, was based on that of the Greeks. The greatest of the Greeks as playwright and producer was Æschylus, who flourished about 500 B.C. There appears to be little doubt that it was he who first introduced scenery in connection with dramatic representations. To him, too, the credit is due of having erected the first permanent theatre. Previously, the dramatic performances of the Greeks had always been given in the open air.

The scenery used by Æschylus was stationary scenery; indeed, it was not until more than 2000 years after his period that movable scenery was first introduced. There has been much discussion as to the actual date when this took place. Some students of the Elizabethan drama have asserted that movable scenery was used by Shakespeare and his contemporaries; but the proofs of this are not at all definite. The general consensus of opinion is to the effect that Davenant, the English playwright, was the first to apply this novelty. At any rate, there is convincing evidence that in or about the year 1662 he produced a play with the accompaniment of movable scenery. Probably this scenery was very clumsily contrived, but it embodied the principle on which the cleverest effects of the present day are based.

And how clever some of those effects are! It is worth the while of anybody at all interested in 3theatrical matters to inspect the scenery arrangements at an up-to-date theatre. At every turn he will find something to wonder at and admire. Quite recently at one of the London theatres there has been installed a new electrically driven equipment for raising and lowering cloths, sky borders, curtains, and for setting ceilings, etc. It has proved a great success. Wire is used instead of the old hempen ropes, and this is an enormous advantage from the fire-risk point of view. Further, it has enabled the number of stage hands to be reduced. The equipment works with far less noise than the ordinary hand system, and much more quickly and certainly. It seems quite likely that before long this electric-power system will be the one adopted at all the big theatres, but for the smaller theatres, and certainly for the halls at which amateur companies usually give their performances, the old system will continue to be used.

There have been a number of books issued during recent years on the subject of Scene Painting and Stage Effects. I have read all of them, but have come to the conclusion that none effectively covers the ground. Some of these books are evidently produced as advertisements of dealers in paint for scenic purposes. Those dealers doubtless know much about the making and mixing of paints, but it does not follow that they are acquainted with the art of placing the paint on canvas, any more than it follows that a maker of pens or paper is a literary man. Others of these books are far too technical, both as regards matter and style. The perusal of them cannot possibly be of much assistance 4to the amateur in scenic painting, however intelligent he may be. It almost seems as if the authors did not really wish to impart information, but only to publish a book showing their own intimate knowledge of abstruse terms and definitions.

I think the present book will be found to be free from the faults to which I have just referred. It is not an advertisement of any man’s goods; it has been kept as free as possible from technical difficulties; and it is an honest endeavour to cover the ground with which it deals. The book includes within its scope the whole art of scene painting. It deals with the problem of perspective in as clear and simple a way as possible. It gives designs of typical scenes and of the furniture appropriate to such scenes. Further, it contains much useful information as to stage building—from a platform for a drawing-room entertainment or a fit-up tour to an elaborate permanent structure. In addition to all this it describes in detail the working of scenery, including curtains, full scene sets, a chamber set, etc.

The need for such a book is evident. Every town of any size has its amateur dramatic society, and in the big towns and cities those societies are to be counted by the dozen. Amateurs quite rightly pride themselves on doing as much as possible in connection with the performances they give; they make their own costumes and even sometimes write their own plays. Now they will be able to paint their own scenery. In the case of almost every amateur dramatic society, there is at least one member who has some knowledge of the art of painting. With the aid of the advice and information given in 5this book he will be able to apply that knowledge for scenic purposes. Without such advice and information, however clever a painter he may be, he could not so apply it. There is a world of difference between painting a picture to hang on the wall of a gallery or a drawing-room and to be inspected at short range, and in painting a scene to form the background of a stage and to convey a bold and definite effect to hundreds or thousands of people inspecting it from all parts of a big hall or theatre.

In this connection I may mention a performance which I witnessed in the provinces recently. It was given by a local amateur society. The play was a good one, and the acting was good, but the scenery was lamentably poor! It had been painted by two talented artists, both of whom have several times exhibited at the Royal Academy, but they had failed entirely to get the effects at which they had aimed. Looked at from a few yards’ distance, the scenes were simply a blur of paint; yet, when I went round after the performance and inspected them closely, I found that as ‘pictures’ they were admirable productions. That is the difference in a nutshell—a scene may be and should be picturesque, but it is not a ‘picture’ in the Royal Academy sense of the word. At other amateur performances I have seen various shifts resorted to. The background of the stage has been covered by ordinary wall-paper and hung with ordinary pictures. The effect has never been what was intended. The play produced may have been a comic one, but, in my case at any rate, quite as much laughter was excited by the faulty scenic effects as by the jokes uttered by the actors.

6As a matter of fact, there are very few working scenic artists; the profession may quite fairly be termed a close corporation. The artists realise that so long as their number is few, their individual receipts will be high. Instead of welcoming any addition to their ranks, they do their best to keep others out. To go to one of these scenic artists for information as to his profession is simply to waste time. I heard a story the other day of a man who knew something about the business, and who wanted to learn the more intimate secrets. He obtained the acquaintanceship of a skilled scenic artist and did his best to extract those secrets from him. He failed utterly. He even went to the extent one night of deliberately making the artist drunk, or nearly so, in the hope that then the man would talk. The man did talk, but none of his talk was about his art. Although not master of his faculties, he still had the sense to know that he must not impart any information about his art. He talked about his wife, his mother-in-law, and many other interesting subjects, but not a word fell from his lips as to scene painting or stage effects.

Some dealers sell paper scenes, which to some extent supply the need felt by amateur societies—but only to some extent. The scenes are usually of miniature size and are inadequate for large stages; besides, the mounting of them on canvas is a difficult and expensive task, and even when it is performed the result is often imperfect, for paper soon crumples up on a canvas background. The best thing is for the amateur to do his own work if possible. This book will make it possible. 7All the various points are dealt with. The reader will learn as to the right sort of canvas, the right sort of glue, and the right sort of brushes. Valuable hints will also be found as to scenic artists’ frames, the stretching of canvas, the use of pulleys to pull up canvas, stencilling, and many more necessary matters. Exact diagrams as to all these are given. The pages dealing with the construction of a platform will be found very useful. On how many occasions is not such a platform wanted! There is the need for one, not only for the purpose of dramatic representations but also for concerts and various social functions.

The book deals very fully with stage effects. The reader will learn the best and simplest ways of producing the effects of rain, snow, hail, thunder, galloping of horses, etc. Occasions for the use of these occur in very many plays performed by amateurs. The realism of such effects is very great if they are produced properly. The truth of this may be proved at any of the cinematograph theatres; the impression of the pictures is again and again intensified by some effect worked behind the curtains. Stage lighting is also adequately dealt with in the book. This section will be useful to many amateur societies. It is not sufficient to have the right sort of limes—there must also be a full knowledge of the best way of working those limes. That knowledge will be obtained from a careful study of the section in question.

Every endeavour has been made to illustrate the book in the best possible manner. The plates showing typical scenes will assist the amateur 8scenic artist very considerably. The diagrams as to perspective have been made as simple as possible, with due regard to the necessity of their illustrating the accompanying letterpress adequately. Indeed, the whole note of the book is the coupling of simplicity and efficiency.

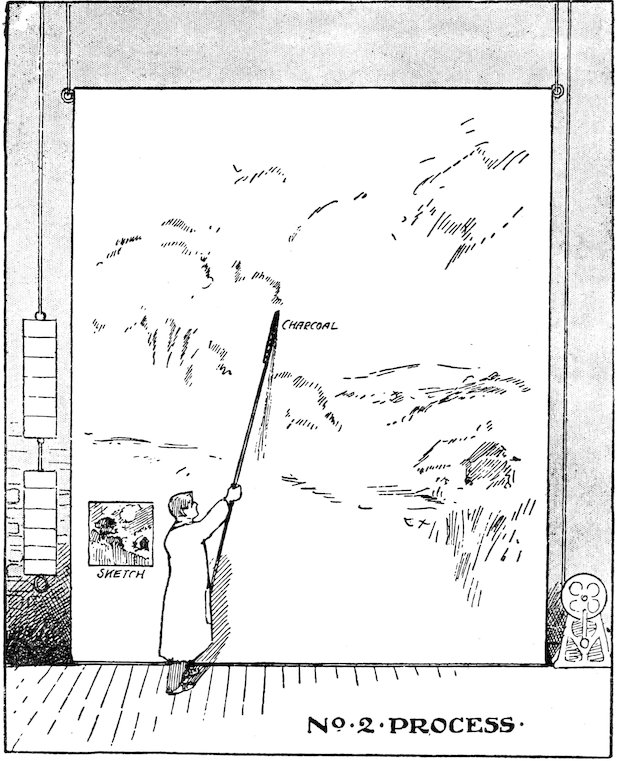

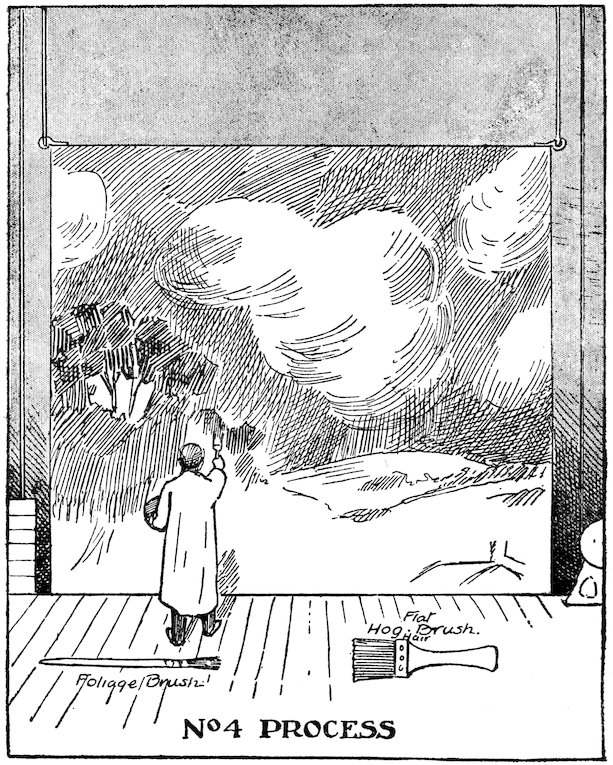

The professional scene painter requires a very large room for his work, and it must be so situated that there is a large space below the room and an equal amount of space above it. This arrangement is necessary because, with one exception—to which I will presently refer—the scenery is painted from the top downwards, and as the scene painter finds it convenient to stand on the floor of the room while he is at work, it follows that the canvas must first be dropped through a slit in the floor. It is then hauled up to a convenient height, and when all the part which the painter can reach is covered, it is drawn upwards, so that another blank piece of canvas faces the painter. By the time the lowest part of the canvas is in place, the top is therefore well out of the painter’s reach.

If the amateur scene painter can arrange an outhouse in this way, he will facilitate his work, but if the scenery is not very large, he can work fairly well on the canvas if he spreads it out on the floor. In that case he will first roll up the canvas and then unroll a portion of it. After he has covered that he will unroll some more, and will continue the process until he has covered all the canvas. In some cases, however, the scene painter will find 9that the more convenient method is to suspend the canvas in some way with ropes and pulleys.

![[Stage]](images/i_p09.jpg)

The exception to this customary plan of working to which I have alluded, is when the painter has to produce a street scene on a back cloth or some scene in which the artist’s knowledge of perspective comes into play. For a scene of that description it is best to begin in the middle of the canvas. The necessity for this plan will be appreciated when the chapter on perspective has been studied. A street scene is, perhaps, the most 10difficult of all scene painting to do well, because if the perspective is not right the effect will be not at all what is required; the houses depicted in the scene will appear to be in danger of toppling over, and the whole effect will be grotesque.

All scenery is painted on ordinary flax canvas which, in the first case, is only a yard wide. Strips of the canvas are sewn together to make a large sheet. The amount of preliminary work required may be judged from the fact that a full-sized ‘frame’ for a theatre measures 60 feet across by 45 feet in height.

The canvas is joined together in a special way, so that the joins may not be seen and a perfectly flat surface may be presented. The simplest way to learn this process is to take two sheets of paper and set to work in the following way:—

Lay half a sheet of note-paper on the top of another, so that the under one projects about an inch beyond the upper; paste along both edges of the papers and then fold the top paper over the bottom paper, but before doing so push it up about a quarter of an inch, so that it adheres to the bottom paper. The two papers will then be held together firmly and the surface will be practically flat.

![[Framework]](images/i_p11.jpg)

12After the required area of canvas has been decided on, it must be mounted and stretched according to the purpose for which it is required. In dealing with a back cloth, cut cloth, or act drop, the canvas is merely stretched tightly across the batten and nailed at intervals, it thus hangs loosely below; the surplus material, if properly dealt with, drops through a slit in the floor as before mentioned.

![[Framework]](images/i_p12.jpg)

In the case, however, of wings and other moveable pieces a proper wood framework is required, as shown in many of our illustrations. On this framework the canvas should be stretched as taut as possible, which can be done either by tacking the bottom and then pulling the canvas over the top batten with the hands while an assistant nails it, or, by using the special pincers shown in the accompanying illustration. These pincers have a long gripping surface with a toothed surface, one set of 13corrugations fitting into the other. Naturally this grip cannot slip when the pincers are closed, and a great purchase can be obtained, which makes satisfactory stretching a practical certainty.

When the canvas—which, by the way, costs about eighteenpence a yard—has been joined and framed up it is ready for ‘priming.’ The effect of this process is to give it a white surface to which the paint will adhere. ‘Priming’ is made by dissolving whitening in water and adding size. The usual plan is to use about half a bucket of water. Whitening is placed in this, and after it has been soaked till it is fairly soft the surplus water is poured away. The bucket is then filled up with melting size and is well stirred up. It is necessary to be careful about the quantity of size, because if too little is used the paint that is afterwards put on the canvas will come off when it is rubbed; thus, if a back cloth is painted and rolled up, the labour will be wasted.

When the ‘priming’ has been made the canvas is spread out and the painter is ready to begin the first part of the work.

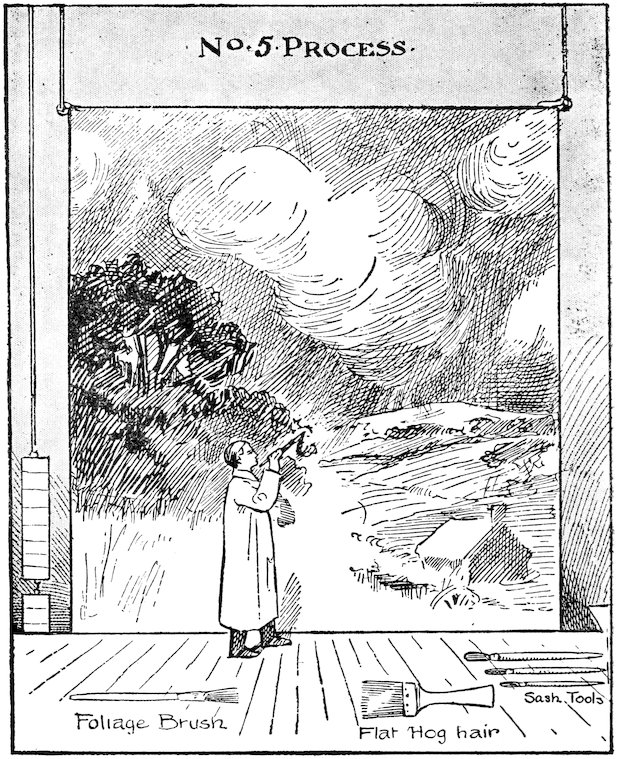

This is a convenient point at which to describe the brushes required by the scenic artist. He should provide himself with the ordinary painter’s sash tools, and it is as well to have them in all sizes, from No. 1 to No. 12. The latter is about an inch and a half across. The brushes are not perfectly round. It is also as well to have a brush with a long handle for use when painting foliage.

The ‘priming’ is applied with what is technically known as a ‘double-tie’ brush; it is merely an ordinary whitewash brush. A brush of a similar 15kind but half the width—known as a ‘single-tie’ brush—is also needed for painting tree trunks and other large surfaces.

After the ‘priming’ has been applied the canvas must be left to dry thoroughly before it is used. While our canvas is in this state we may well turn our attention to the paints.

The scene painter’s colours are known technically as ‘distemper colours.’ They are bought in the form of powder, and the only preparation they require is the admixture of water. The usual proportion is one pound of colour to a pint of water, but some colours will ‘take’ more water than others; thus, ivory black requires more water than vermilion. The powder is merely stirred up until it dissolves, but each pot of paint will require an occasional stirring while it is being used. The painter will also require a small pail of water for ‘letting down’ his colour and a half pail of dissolved size for mixing in before applying the paint and thus causing it to adhere to the canvas, otherwise the paint on drying would fly off in a powder. The artist will also need some sticks of charcoal.

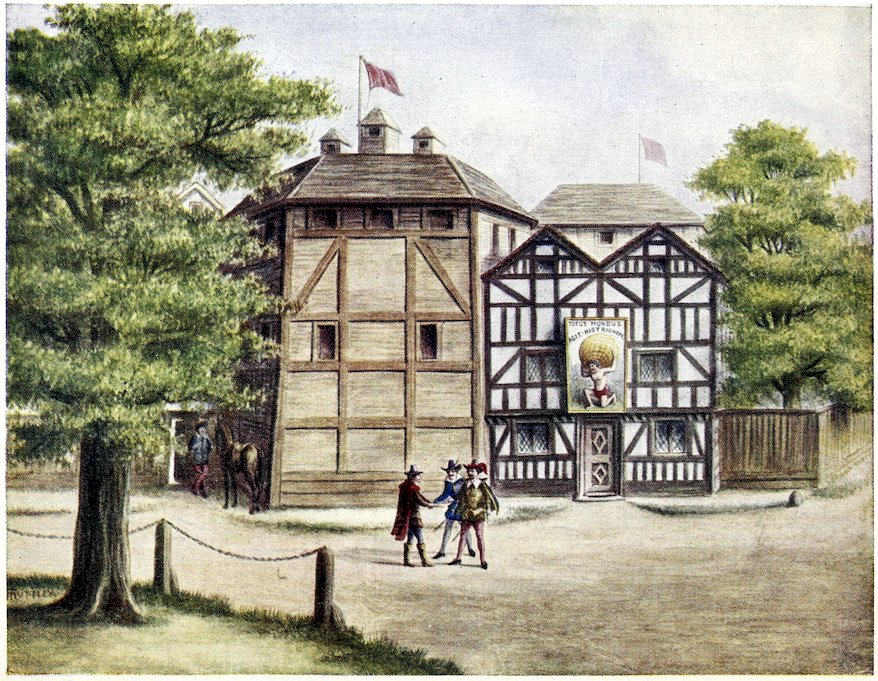

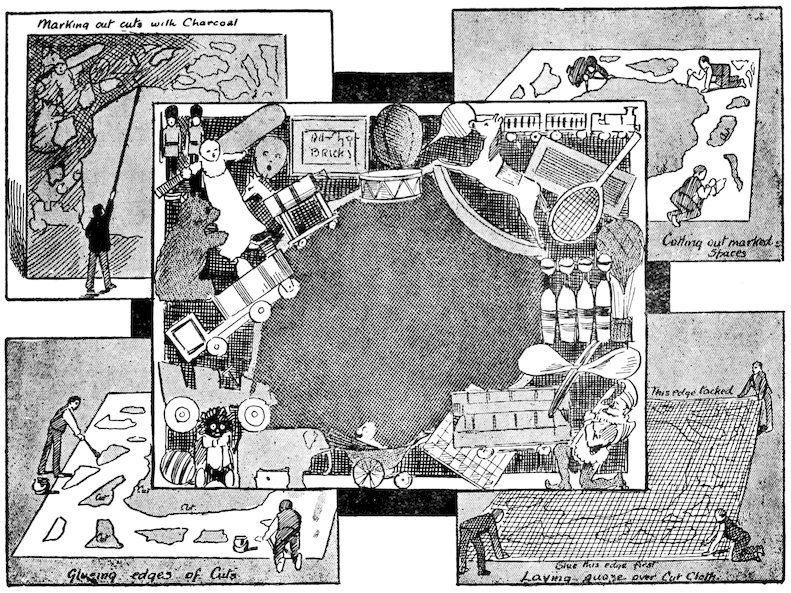

The first step towards converting the canvas into scenery is to sketch out a rough design on the canvas with a stick of charcoal, but before this is done it may be as well to make a design of the scene required on paper. With this copy before 16him the amateur can go to work with his charcoal. If he is going to paint a tree it will be as well to have a stick of charcoal fastened to a long stick.

No words can tell the artist exactly what colours he should use, for everything depends on the mixture of the colours. The best plan for learning 18this part of the work is to get an old piece of scenery and try to copy it. At the same time the learner should make a note of the colours that have been used to produce such effect. The artist must remember that the effect he has to produce must not be that which he sees himself, but that which the scenery will present when it is hung up and shown by artificial lights.

In the painting of a tree or any outdoor scene the artist is sure to want to produce the effect of sunlight and shadow. The former is generally produced by painting with a mixture of yellow ochre and chrome yellow. The effect of shadow is produced by painting with a mixture of crimson lake, Prussian blue, and a very little ivory black. When this mixture is made and applied, the artist will probably imagine that it contains far too much crimson, but when the scene is lit by artificial light this effect is subdued. Nevertheless, one often does see a shadow effect on a stage in which far too much crimson has been used.

The exact proportions of these mixtures and the various shades needed to paint a tree can be determined only by experience.

The artist may have to paint over a scene three times. He will always have to do it twice, but the first coat is very light, merely a sketching in of the outlines made by the charcoal.

After a tree has been painted, the foliage must be cut out very carefully. When the scene is finished and the leaves and branches have been cut out, this part of the scene is laid out flat with the painted side to the floor and a piece of fine black gauze 19is pasted at the back of it. This has the effect of holding out the foliage; without the gauze at the back of it the foliage would fall ‘in a heap’ at all the places where it had been cut. The black gauze is not seen ‘from the front’ when the lights are on the stage.

The painting of a fence for an outdoor scene is simple enough. After the fence has been painted, the canvas is pasted to one or more other pieces to stiffen it and the parts of the canvas not painted are then cut out with an ordinary saw. The painted fence is then stiff.

Having produced his piece of scenery the amateur is strongly advised not to neglect one important precaution, and that is to paint the back of the canvas with a fireproof solution. It is now a rule at all theatres and music halls throughout the country that all scenery and properties must be fireproofed. Things prepared in this way do not readily catch alight: when heat is applied they only smoulder; they do not burst into flames. Many a theatre fire has been stopped at the outset through one of the ‘props’ having been fireproofed.

The amateur artist who sets out to paint a piece of scenery for the first time in his life will probably be far too painstaking in his work, or rather he will take the wrong kind of trouble over it. He must remember that all his work is to be viewed at a distance and under very peculiar conditions. There is a blaze of light from the ground upward and from the sky downward, and frequently from both sides 20of the stage. Therefore it is useless for the amateur scenic artist to work as though he were painting a picture. He must always bear in mind what his work will look like when it is lit up on the stage. He is strongly advised to begin at first with broad effects and to watch, if possible, to see what effect his first work has when it is lit up on a stage, before he goes on to anything more ambitious.

21A simple plan for an amateur who is working in the dark, so to speak, is to proceed in this way. Let him get hold of an old scrap of scenery and copy it as though he were drawing a picture of it. Then let him put in the lights and shades, and he will soon see for himself how to procure the effects demanded in stage scenery. His chief fault will probably lie in a failure to appreciate the effect of what he is painting when it is presented in stage light: he will probably think that there is too great a contrast in his lights and shadows, but he must remember that the stage lights have a softening effect on such contrasts, and therefore in a stage picture they must be over-emphasised. The amateur actor is usually just as nervous about overdoing his make-up, because he does not take into consideration the effect that the stage lights have on a face that is not made up. The most unbecoming little shadows are cast upon the face, and one of the secrets of making-up well is to ‘allow’ for these by means of grease paints applied in such a way that the complexion seems to be entirely natural.

The scenic artist must therefore remember that his work is going to be judged under circumstances very different from those under which it is done, and he must make allowances for that fact, otherwise his scenery will be grotesque. After all, very few 22scenes, especially out-of-door scenes, in theatres, are really life-like. They suggest the open-air scene rather than depict it.

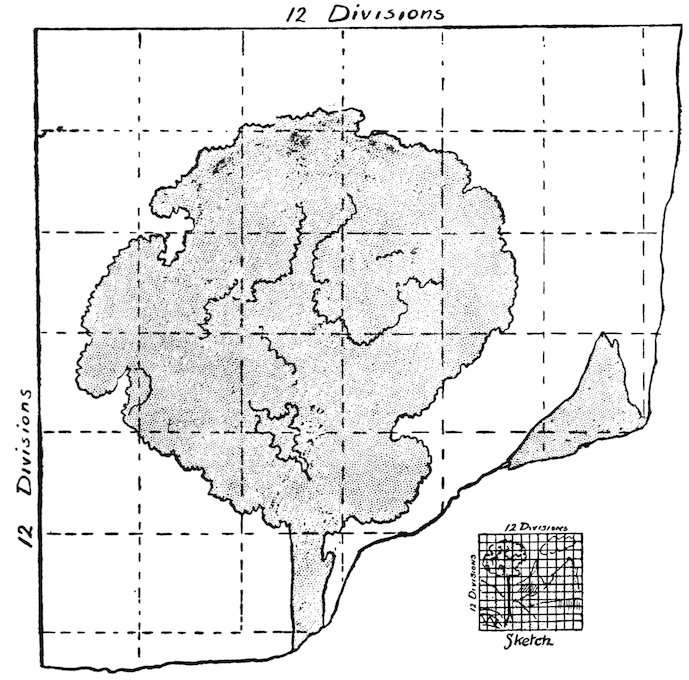

Portion of Canvas Showing how to enlarge Sketch to scale.

The best method is to sketch on to the canvas, then rule up the design into a number of equal squares or rectangles, then using a chalk line divide the canvas into precisely the same number of spaces.

24The rest is easy; it is only necessary to follow the original design, square by square, and map it out on the canvas.

The sketch should, of course, be in absolute proportion to the cloth. If it is square, any square is right. If, for instance, the cloth were 30 feet by 20 feet, the sketch should be 30 inches by 20 inches, or 15 inches by 10 inches, as most convenient.

If the reader is familiar with even elementary perspective, this chapter will not aid him, for it is not within the scope of this work to instruct in a science which is adequately covered by literature especially devoted to the subject.

The object of this chapter is to give the amateur an opportunity of producing by the simplest methods an interior or exterior back cloth which will be reasonably convincing in its perspective lines.

For this reason, the orthodox means of obtaining accuracy in fixing the vanishing point, scale, and all other technical explanations have been omitted as being useless unless the reader has the assistance of a qualified student to help him in deciphering the diagrams.

It must not be assumed, however, that the result of following these few instructions will be a something that is not perspective. With intelligence a very respectable interior, for instance, can be set out, which will satisfy most people, if not the professors.

If, on the other hand, an attempt is made to draw out a scene without some method of perspective, the 25result will be in all probability ludicrous, and ‘Chinese’ in its lines, producing an irritating effect on an audience of discernment.

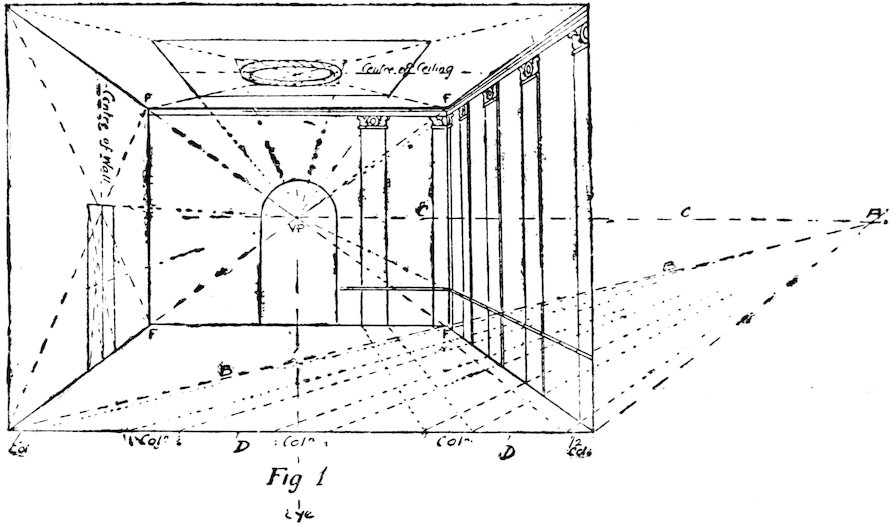

Perspective is the view of objects flat or perpendicular, as they appear to the eye, and not as they really are. The farther an object is from the eye, the smaller does it appear to be, until at last it seems to vanish at the limit of vision, that which we call the vanishing point. If we look through a long straight tunnel we see ground, sides, and roof all converge to a point of light—the other end. If the tunnel is lit by lamps at the sides, they will be seen to get smaller and smaller and closer and closer together as they approach the outlet. They do this in strictly decreasing proportion, and no two spaces are alike. To attempt to draw these spaces correctly without a method would be futile.

Now all straight lines, whatever they are, rails, bricks, lamp-frames, etc., that have their ends to the mouth of the tunnel, get closer and closer together as they recede, until they appear to nearly meet at the point of light, and this fact is the germ of perspective drawing. The horizontal lines, however, such as sleepers and the sides of the lamp, although they decrease in width and length, remain quite parallel to the very end of the tunnel.

Therefore we have two leading facts, (1) that all lines going away from us tend to meet, and (2) all lines across our path remain parallel. If our tunnel is a square one, and we chop it up into a number of sections, what have we but a series of rooms end on end. Consequently, keeping the principle of the tunnel in his mind’s eye, the reader should have 26little difficulty in setting up a correct interior. Of course doors, windows, columns, pictures, etc., have their widths to be determined, and these must be laid out on the same principle as the tunnel lamps.

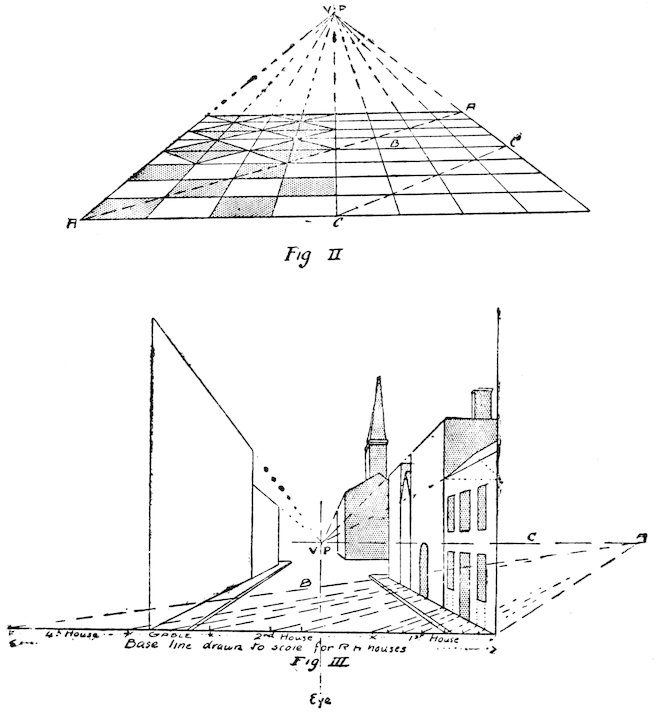

Fig. 1 of the illustrations shows a simple interior including ceiling, floor, back wall and two side walls. It will be seen that from corner to corner of the canvas are diagonal dotted lines, and where they cross in the centre is a point marked V.P. which is the vanishing point or ‘end of the tunnel.’ As we do not require an endless room we cut off several miles of it and put a back in. This can be done by dividing each of the diagonal lines into four parts, and drawing up to the four points (F) to make the back of the room.

We now have something like a square room, with four equal sides, on the back wall we put what decoration we like without troubling the 27vanishing point except that no object that is equal to a similar one on the side walls must exceed it in height, although it may in apparent width. To set out the columns on the right-hand wall, draw a line (B) from the left-hand front corner through the right-hand back corner of the floor, and continue it on until it cuts across a horizontal line (C) drawn in through the vanishing point, thus forming another point marked A. Now as we have considered this a square room, of course our base line D is really the same length as the side walls, so we mark our columns on D in their proper places. Then we draw lines from each of such marks to the point A, and from where they cut the floor line of the wall we draw perpendicular lines up the walls to give us the elevation of the columns in perspective spacing and width.

The left-hand walls and the ceiling show a simpler method, when merely a single central feature is wanted. Simply draw diagonal lines corner to corner, and then a vertical or horizontal one, and the exact centre is found; then mark out the feature, seeing that all the going-away lines tend towards the V.P. The position of the V.P. as shown is not a fixed rule, but merely for simplicity of instruction: it may be above or below the centre of the back wall, or to right or left, giving a different aspect of the room; the general rules described still apply.

Fig. 2 shows a method of setting out a parti-coloured paved floor. Divide the front line into a number of equal spaces, draw lines to the V.P., then A to A, then horizontal line B, through the centre cut, 28which allows C to C to be drawn. Then draw the other horizontal lines, cut vanishing lines, and the floor will represent a draught board in perspective, cross each square with diagonal lines, and the pattern can be made diamond-wise. With this basis to work on, many geometrical patterns can be set out in perspective, and of course a ceiling decoration would be painted on similar lines.

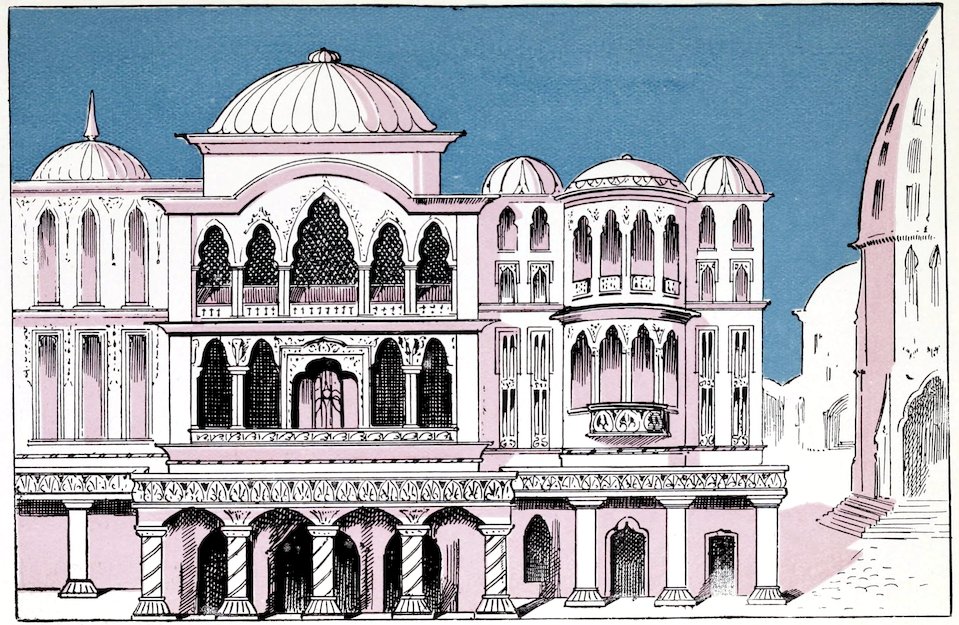

Fig. 3 is a street scene in perspective, it is very 29much on the lines of Fig. 1 except that the spacings are irregular, but they are arrived at by the same methods. We have only shown the right-hand side of the street, as the other side can be set out by reversing the procedure. Assuming the street to be 60 feet wide and the four houses together say 80 feet, the base line must be extended to show this roughly to scale. Then from the V.P. draw the horizontal line C, and from the left-hand end of the base the line B, then cut at A, and that is the point to which all the lines of the vertical features of the houses must be drawn. Then proceed as described for Fig. 1. We have not included the Church, as it means too considerable an extension of the base line for reproduction.

Treat the left-hand side of the street similarly, but vary the detail to fancy.

The heights of the various buildings are immaterial so long as every roof and cornice line runs to the V.P.

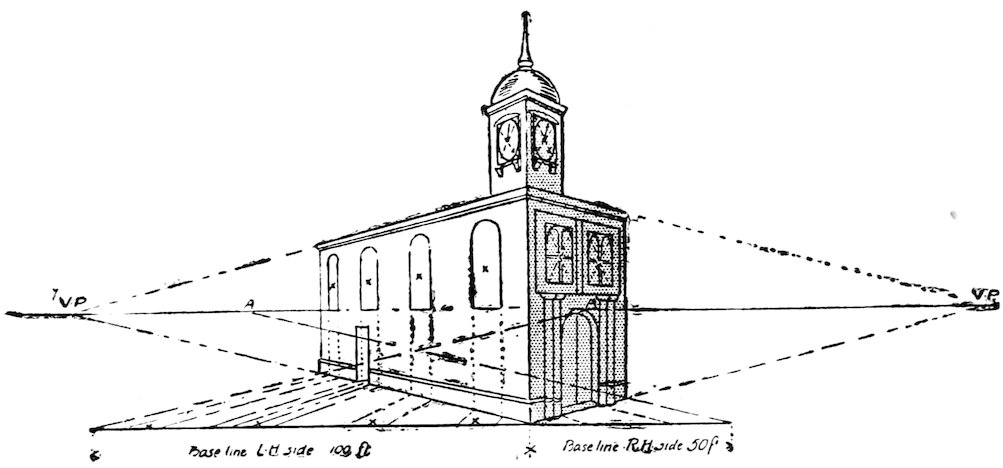

All the foregoing instructions have been for parallel perspective, where but one vanishing point is required. Fig. 4 illustrates an instance of angular perspective, where two sides of a building recede from the eye.

For first efforts at scene painting, angular perspective can be ignored by the simple evasion of not including buildings on the angle. But, strictly speaking, angular perspective is the more exact of the two, and when the reader has grasped the central idea of the vanishing lines, he should essay the angular in his scenes to obtain variety and freedom.

30In Fig. 4 two vanishing points are required, but they must both be on the same horizontal line, lines to right and left of the building are drawn out to their respective V. points. The base lines for spacings can be utilised as in Fig. 3, but one for each side of the building must be set down.

Perspective drawings should be made to scale on paper. After finishing rub out guiding lines, and square up paper as described in another part of this book, and so transfer sketch to the canvas. Never place the vanishing points above the centre unless the scene is to be viewed as from a hill.

In the small space at my command much has been omitted from this chapter, and the ambitious amateur would do well to obtain standard books on perspective, and study the science fully, but satisfactory results can be obtained by following these simple instructions carefully without further tuition.

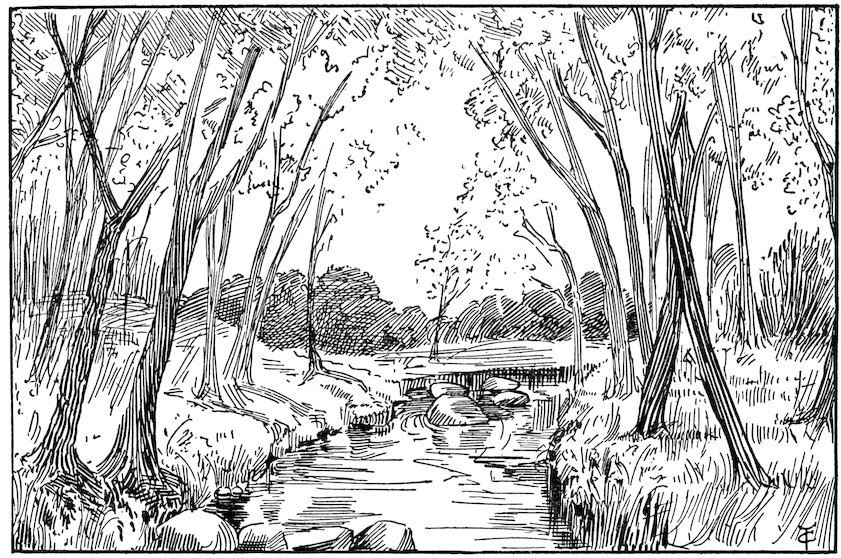

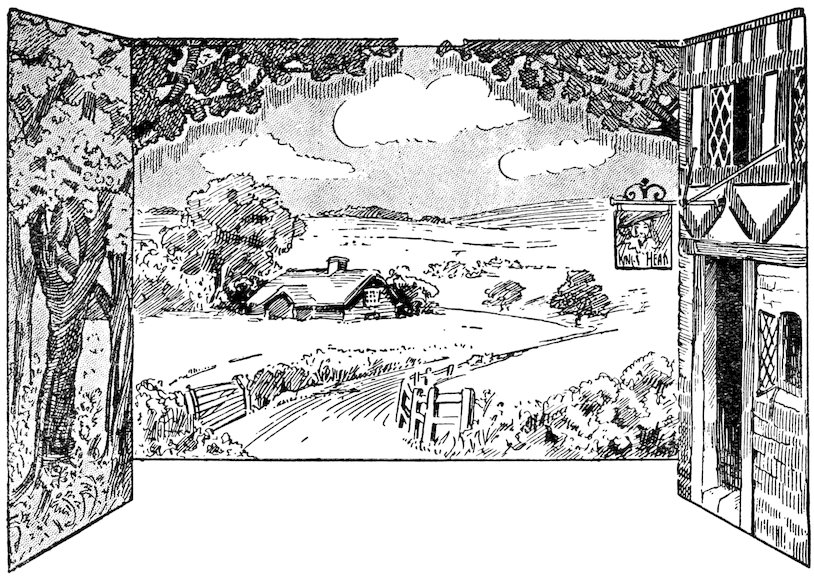

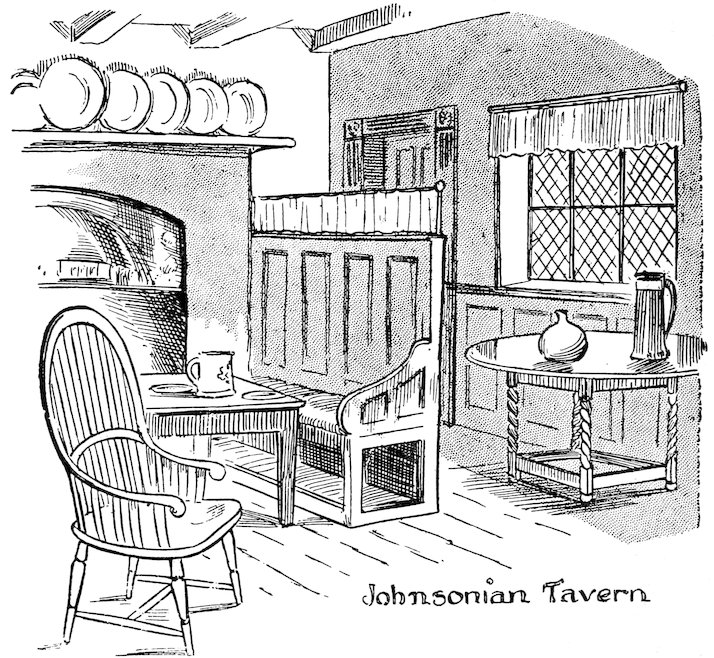

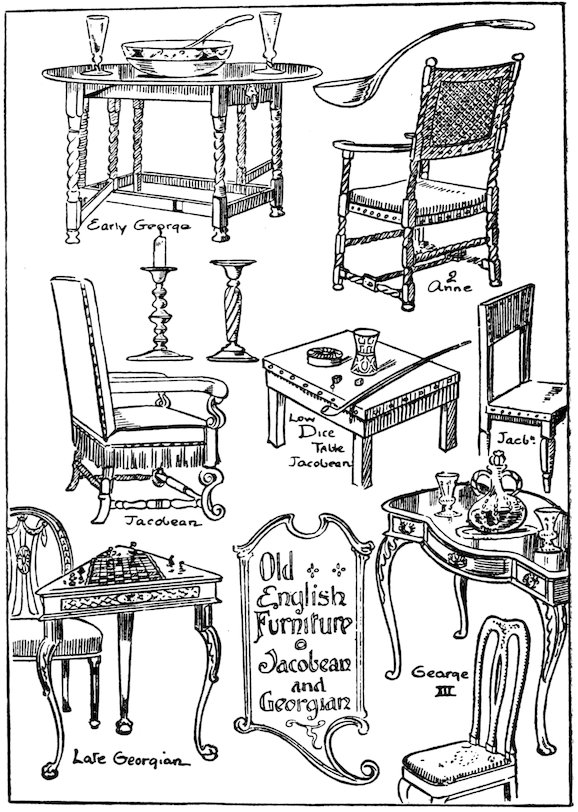

The earnest beginner will no doubt desire to adapt his designs to the play to be represented, but he will usually find very little guidance in the author’s directions. Such directions are scant and laconic, except where the position of a door, window, or fireplace is concerned. This reticence of authors is a blessing rather than a restriction, for such directions as ‘Interior of a cottage,’ ‘A drawing-room,’ ‘A stile by a cornfield,’ ‘A woodland stream,’ give the scene painter a free hand in depicting that which his fancy may dictate. A number of the illustrations in this book will be found useful as suggestions for exteriors and interiors suitable for a goodly collection of domestic plays dealing with home life, but where, as in many of Shakespeare’s plays, the scenario lies in Italy and other parts of Europe, or as in The Only Way and The Scarlet Pimpernel, Paris of the Revolution is dealt with, some attempt must be made to get local colour or the effect will be ludicrous. There are occasions where one need not be too particular. For instance, a Baronial Hall covers a long period of English History; it can even be made quite modern when the play deals with personages of ancient lineage, but the amateurs we saw who depicted a stirring incident in the Soudan war inside a Dickensian cottage, required too elastic an imagination from the audience. Where local colour must be got, the scene painter should look up some private prints or illustrations of the period, or, where possible, good 32pictures of the actual incidents in the play, an easy matter in the case of Shakespeare.

Having obtained these, rough sketches should be made from them with all the portions knocked out which are not practicable for stage purposes, but still retaining the essence of the designs. To be truly conscientious the amateur should mount the sketches on cardboard and make them up into models which will give him a good idea of the finished effect.

![[Sketches]](images/i_p32.jpg)

The chapter on perspective gives a method of squaring up, by which these rough sketches can be enlarged to the size required.

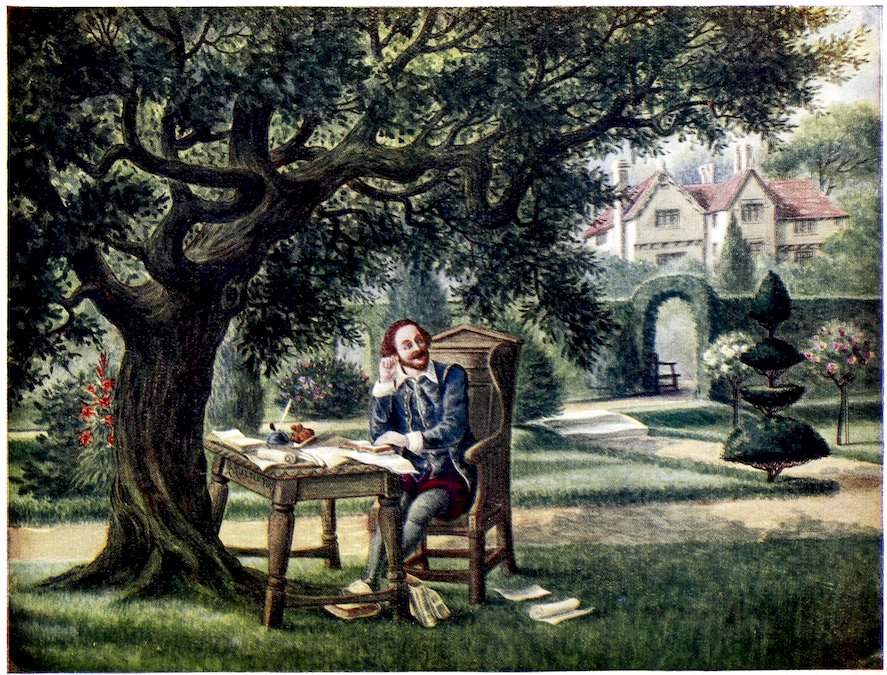

Shakespeare sitting under his favourite Mulberry Tree in the Garden of New Place.

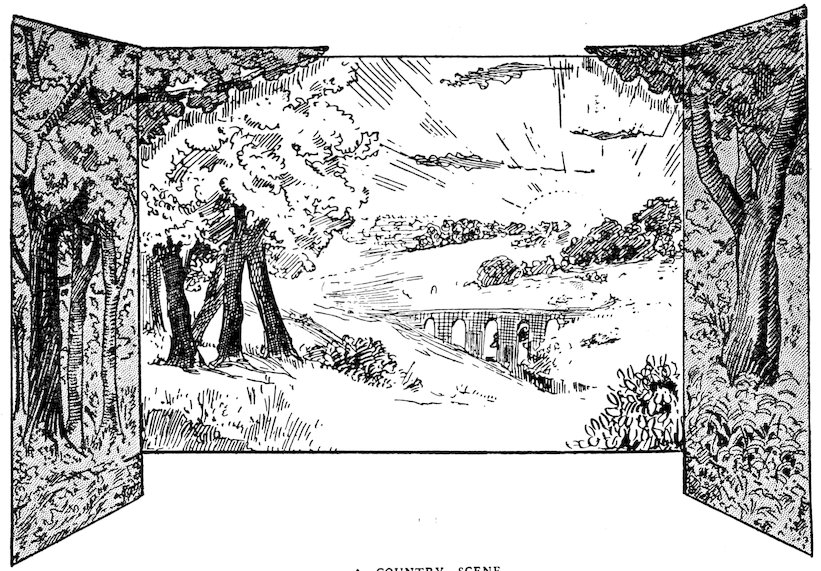

33Landscape will more easily pass muster with the majority of onlookers, but intelligence in designing outdoor scenery is keenly appreciated by those who know, and a landscape that coincides with the locality of the play stamps the painter as an artist rather than an amateur. English landscape can take care of itself, pictures by Birket Foster, B. W. Leader, Alfred East and others provide excellent material. Scotch scenery should be wilder and more rugged, with masses of rock and heath instead of grass, while Irish landscapes should be depicted as somewhat unkempt in appearance, with small stumpy trees. It should be noted also that the character of the fencing changes, hedges to stone walls, stone walls to banks and ditches, and so forth. Where foreign environment is concerned, photographs must be studied, but Italian gardens, which are very popular as back cloths, can be seen copied in many English county mansion domains. With their dark masses of trees, many of the poplar order standing in relief against the sky, suggestions of statuary, fountains, and balustraded terraces, they have a decidedly foreign appearance and are undeniably effective.

Now a few words as to treatment, or what artists would call ‘handling,’ of the subject chosen will be useful, because many amateurs in their desire to be painstaking overdo their work and produce a stiff and angular effect.

Of landscape we can say little, except to urge trying for the broad effect, as pointed out in Chapter I. Do not get trees ‘leggy,’ or with all the foliage on top, like the Noah’s Ark variety.

In the case of buildings and interiors, however, there is considerable difference in treatment. In painting cottage interiors, Elizabethan or Tudor streets, old stone halls, old inns, etc., nice straight 34lines and square corners are all wrong. The main vertical lines of the buildings must not fall over too much, but the half timbering roofs, sashes, etc., can leave the straight road with reasonable impunity. The colouring must be broken up so that no space of wall or roof presents an even toned surface. Buildings at a distance can be quite sketchy with most of the detail left out. There is no need to paint in the tiles of a roof half a mile away, it is a labour that undoes the effect desired.

![[Tiles]](images/i_p34.jpg)

THE BROOK

STREET SCENE. MOONLIGHT

MAUVE SHADOWS. COBALT SKY. FLAT.

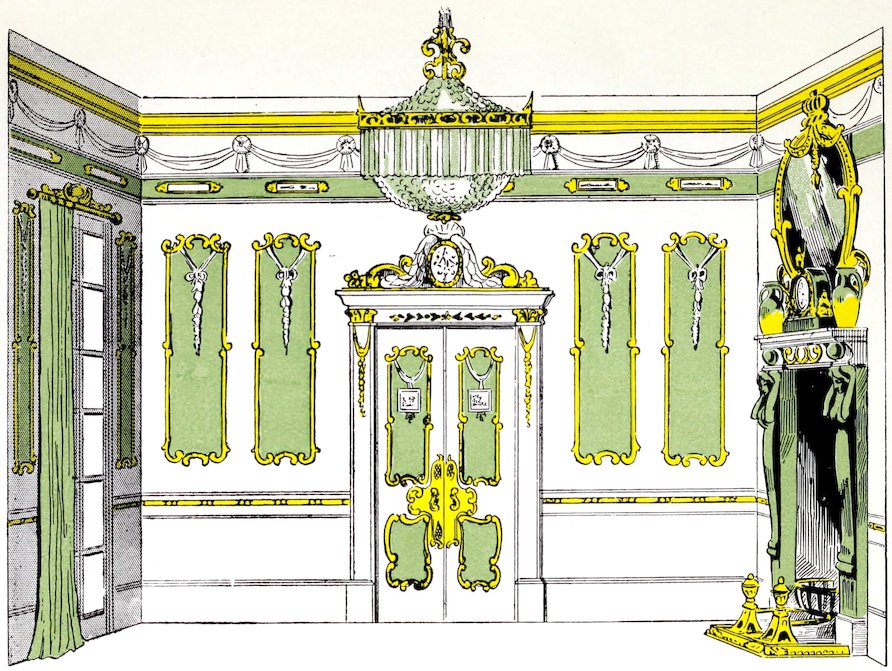

37When it comes to painting marble halls and French eighteenth century drawing-rooms, the foregoing advice must not be followed, for columns and friezes ‘flopping’ over, would suggest indulgence in strong drink on the part of the artist.

ITALIAN PALACE

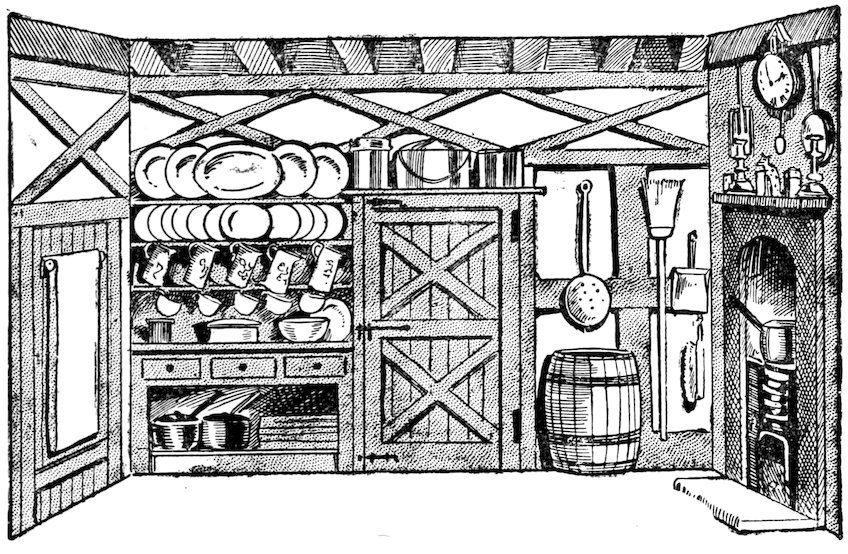

COUNTRY KITCHEN

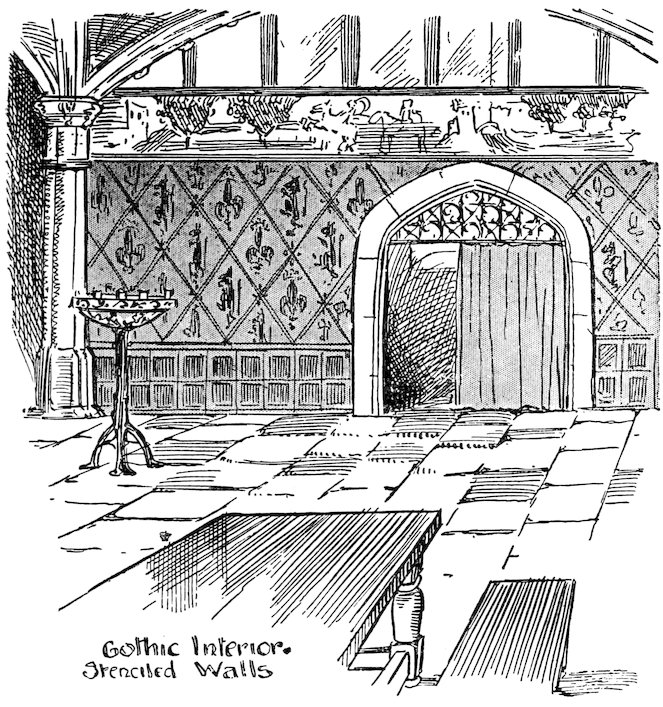

Although requiring accuracy these latter scenes are not really so difficult as the other buildings, for the artistic sense is not so much required as a mechanical exactitude in drawing out the various features of construction. All the straight lines should first be charcoaled and painted in as neatly as possible before any of the decoration is inserted, for it will then not be found a difficult matter to fill in the various spaces by means of stencils, that is, pieces of thin card with the pattern cut out in open work, so that by painting over the outside surface of the card, an impression of the pattern is left on the canvas beneath. Illustrations of these stencil patterns are shown here, but it is not such an easy matter to design and cut them, for unless every portion of the cut-out ornament is connected with tie pieces of card, some parts will drop out. The ‘ties’ however can be put in, even if not wanted as part of the ornament. It is a simple matter to paint them out of the canvas afterwards.

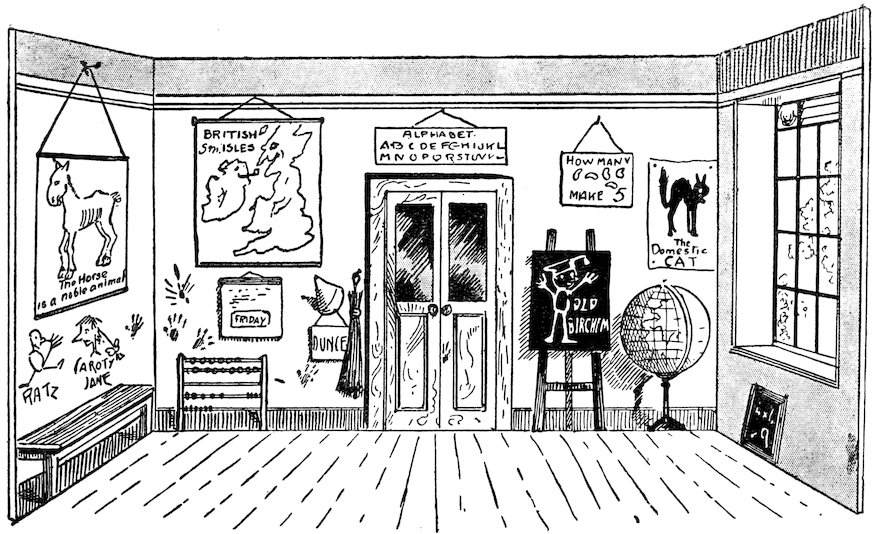

COMEDY. SCHOOL SCENE

A VILLAGE INN

When the whole of a formal interior is set up in line and shadow, the artistic part of the work comes in, in the tinting and colouring, and imitating of gold work, for however well drawn out such a scene may be, the finishing work can be delicately beautiful or crudely coarse, according to the painter’s idea of colour.

A COUNTRY SCENE

44These few simple colour rules may be followed with advantage:—

English Oaken Dining-rooms:—Rich brown with creamy whites, silver and glass, and blue pottery.

Italian Halls and Palaces:—Marble, with gold decorations, black and white flooring, palms, heavy crimson drapery.

Gothic Baronial Halls:—Distempered walls, red and black patterns, with a little gold, white walls above frieze-rails, dark green hangings in doorways.

French Drawing-rooms:—White and gold only, or with pale green and rose-coloured panels.

Cottages:—Limewashed walls, black oak beams, doors, and other woodwork.

Modern interiors require no comment or directions.

This is a side of play production that on no account should be treated as of little moment, or in the frame of mind that feels ‘it will be all right on the night,’ for apart from the possible danger to life and limb from incompetence, there is also that exceedingly irritating business, the long stage wait, which is such a common feature of amateur theatricals.

It is of course best, if possible, to enlist the services of regular scene-shifters to manage the various changes. If there is difficulty in obtaining professional help, volunteer assistance should be properly drilled and rehearsed, and provision must be made for the management and support of each set, or a grievous muddle will be the result.

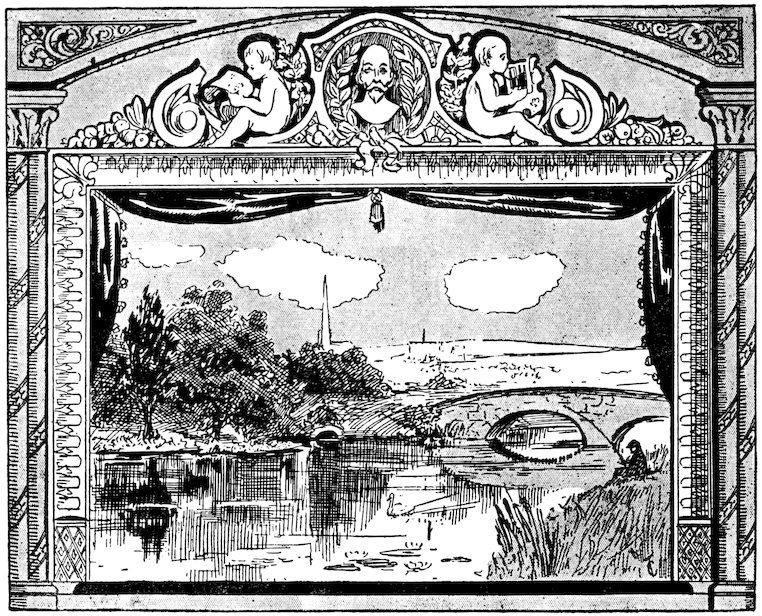

PROSCENIUM

![[Curtain]](images/i_p46.jpg)

47If a hall is hired where stage plays are often presented, the various appliances and fittings will be found ready for use. Where a rough-and-ready platform is erected, the amateur must fix up his own.

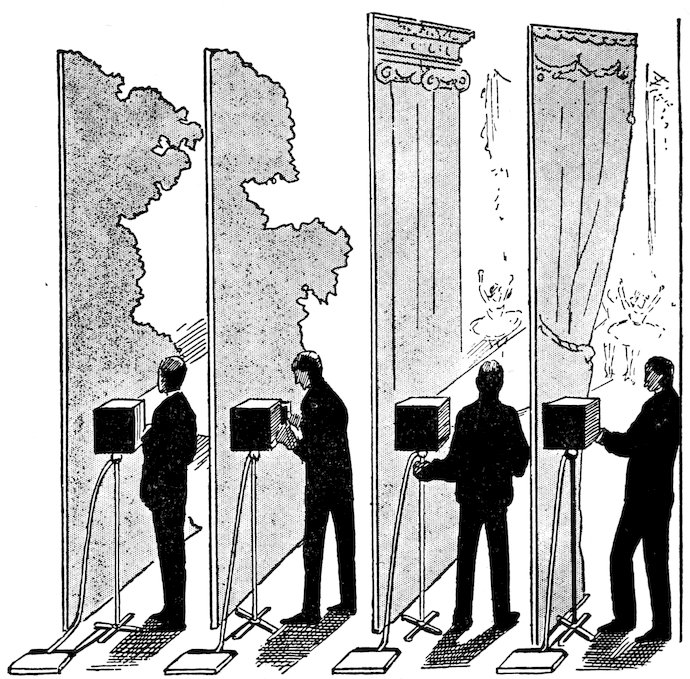

The illustrations we give show how various parts of scenery are dealt with in the large theatres, and we leave the aspirant to play production to adapt them to the necessities of his smaller space.

On some of the great stages these are suspended one behind the other, cables run up through the grid over pulleys, and are lashed round adjoining cross-pieces or cleats (see illustration). Now there is a space above the cloth more than equal to the depth of the cloth itself, so that when it is drawn up (flat) it disappears out of sight and leaves the piece behind completely exposed.

This is not a possible method in a small production, so the various cloths should be attached to rollers and drawn up with ropes, like a simple window-blind, the disadvantage naturally being that, like a blind, the cloth will not always roll up straight.

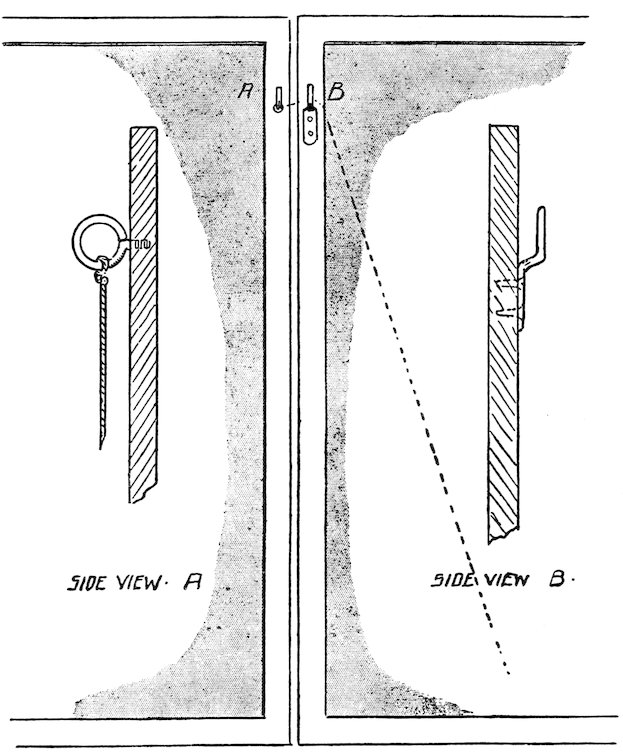

A simple method is here shown for joining two flats together: the cord permanently attached to the ring A, is thrown over the hook B, pulling the two edges of the frame tightly together, the end of the cord then being passed through the nearest fixed screw eye in the stage and slip knotted (see illustration, page 52).

![[Stage]](images/i_p48.jpg)

ENGLISH OAKEN DINING ROOM.

![[Curtains]](images/i_p49.jpg)

![[Scene]](images/i_p50.jpg)

CUT TRAY CLOTH

A SIMPLE CLEAT FOR SCENERY

Screw eye A on one flat, then hook B on the other. Cord is simply thrown over and the flats drawn up together.

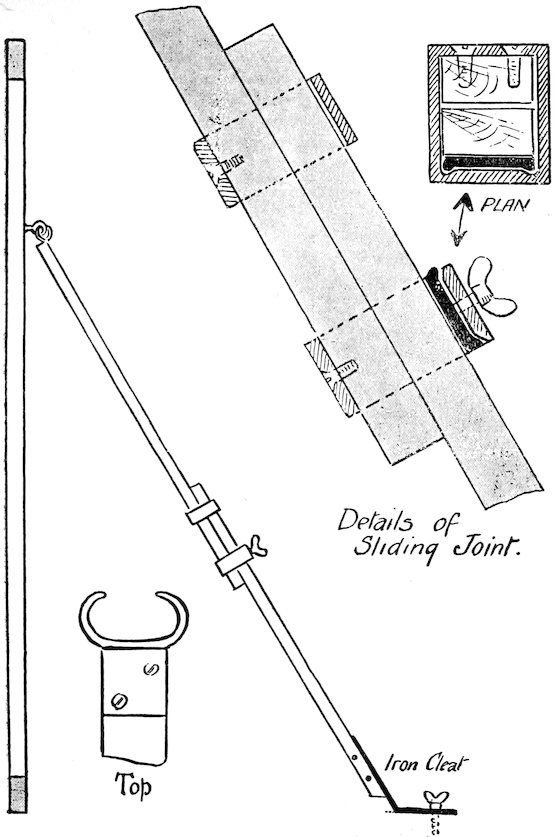

THE LATEST EXTENSION BRACE (PATENTED)

The top end catches in a screw eye on to the scene. Bottom of brace is screwed to the floor by means of a thumb screw.

The centre slides up and down, and fixes with thumb screw into any length desired.

These pieces should have eyes screwed in the backs for engaging hooked rods which are united to the stage and act as supports. One illustration shows the simple form of these braces, the other shows in working detail a patented extending brace which is designed to deal with any piece of scenery that may come to hand, for by loosening the thumb-screws at the joint the brace can be shortened or lengthened to enable the hooked top to catch in the fixed eye on the flat, etc., at any angle.

There are as many ways of building a platform as there are of building a house, but in both cases the great essential is that the finished structure shall not collapse, and at least shall stand fair usage.

The method shown in the diagrams may seem somewhat elaborate for a back drawing-room, but it is safe over a small or a large area, even using the same sections. Like the ‘book-case,’ it grows with your aspirations; you simply require more tressels and more platform sections, and you could extend your platform over an acre, if so desiring.

The tressels are rectangular frames of 2½ by 2 in. wood, with struts in the centre, 5 or 6 ft. long by 3 ft. to 3 ft. 6 in. high; the ties are long pieces of 3 by 2 in. wood, holed at intervals for bolt. The flooring is simply a number of planks nailed on a 4 by 2 in. wood frame, and having strengthening joists at intervals (see drawing). These floorings can be of the most convenient size for storing, as they only form sections of a whole.

57Being provided with the necessary number of pieces you commence to build the platform by spacing out the tressels and fixing the tie-bars to them by means of thumb-screws; the tressels should also be bolted together end to end.

This now forms a firm foundation for reception of the flooring. The sections are laid in position, and should be bolted through their outer frames to each other, so that they form actually one piece. Attach brackets for a curtain-rod to the front and sides, and provide a sheet-iron box, with one side away for your footlights, paint black outside and white in, and string a safety wire the whole length. The platform is now ready for the erection of a stage.

The triangular feet in the drawing of the tressels can be dispensed with in most cases, but they entirely obviate any tendency of the structure to rock from back to front if the tressels’ bolt holes were loose, for instance.

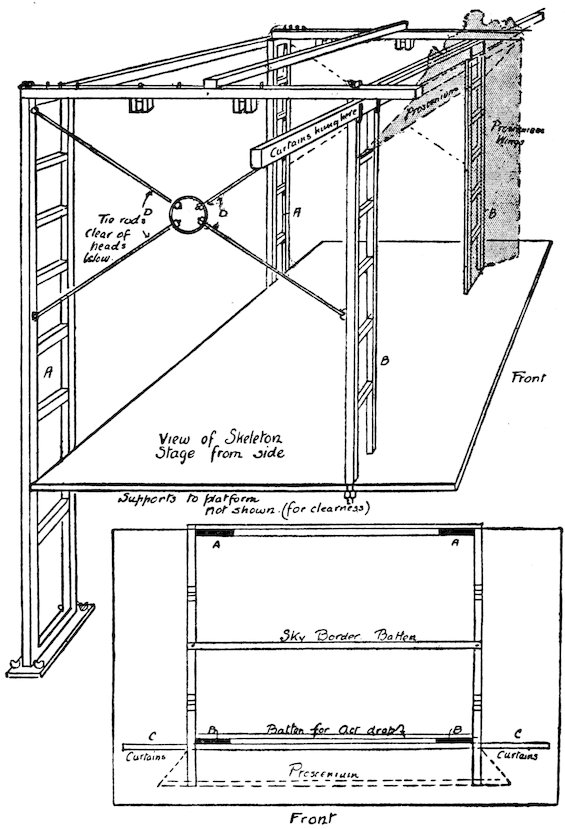

The preliminary remarks to the platform instructions apply here also. There are many, many ways. It is obvious that a scheme for a 12 ft. by 8 ft. will be useless for a 40 ft. by 30 ft. stage. In the latter case, it would be necessary to use a system of bracing and cross-tieing which would be superfluous in the former.

PLAN

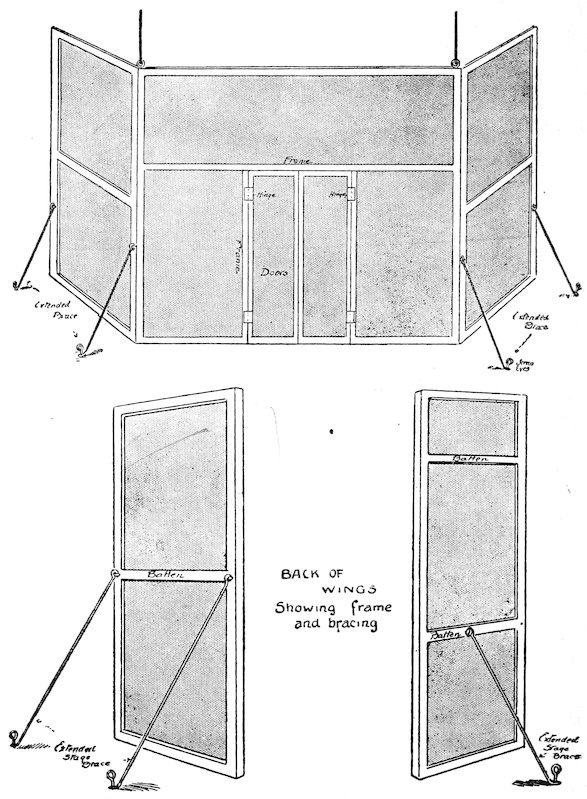

59The illustration gives an example of a stage with a 15 to 20 ft. opening for erection on such a platform as described in this book.

The main supports are four ladders: two long ones to reach the ground at the back, and two short ones which stand on the platform and have pegs to drop into corresponding holes. The back ladders by standing on the floor of the room or hall get a steady support and also a bearing against the back of the platform, thus steadying the whole structure of the stage. If the foot of these ladders may not be screwed down, they should be strongly lashed to the back tressels of the platform. Across the back of the stage there is a strong tie-bar, and the same at the front, but this latter extends some way beyond the ladders and acts as a support for a curtain-rod, the curtain, of course, being necessary to obscure the wings from the sight of the audience.

On the top back to front ties a number of pegs are required for back cloth and sky border battens to drop over according to arrangement wanted.

In the underside of these beams double blocks of wood form slides for the wings. These should swivel to enable the wings to be adjusted to any angle.

If it is necessary to make the curtain beams in two or more pieces, the socket joints should be made close to upright supports to reduce the sagging strain.

Iron tie-rods, as shown in the drawing, certainly stiffen the two sides of the stage, and can be adjusted accurately, but they should be kept clear of head, and are apt to obstruct passage of properties, 60scenery, etc. There must be some disabilities, however, with a temporary stage.

When the skeleton is in place, it is only necessary to mask the front with a painted proscenium, hanging curtains right and left and above, thus entirely shutting out the audience when the curtain is dropped.

The arrangements for raising and lowering act drops, back cloths, curtains, etc., are described and illustrated elsewhere.

There are few plays produced in which a stage ‘effect’ of some kind is not required. The following explanations of how these effects are produced will be found quite reliable, but the amateur stage manager will do well to bear in mind that each effect must be produced shortly before it is actually needed. Thus, if the stage direction says, ‘Horses heard without,’ it will not do to wait until the characters on the stage have reached the point in the dialogue. Otherwise, however good the stage effect may be from a practical point of view, it will seem absurd, because it will appear to the audience to have been dragged in just when it was required.

Possibly someone may say to this: ‘But the audience know that the effect is not real; they know that in reality there are no horses without; why be so particular?’

DRAWING-ROOM.

62To this I reply: ‘If the stage manager and the actors know their business they will make the audience forget for the time that the things they see and hear are not “real.”’ If the play is produced and acted well everything will seem to be so perfectly natural that, for a time at any rate, the audience will forget that they are looking at a play; that is to say, they will forget the artificiality of it all. It is by attention to the smallest details of the production of a play that the stage manager will succeed at his work.

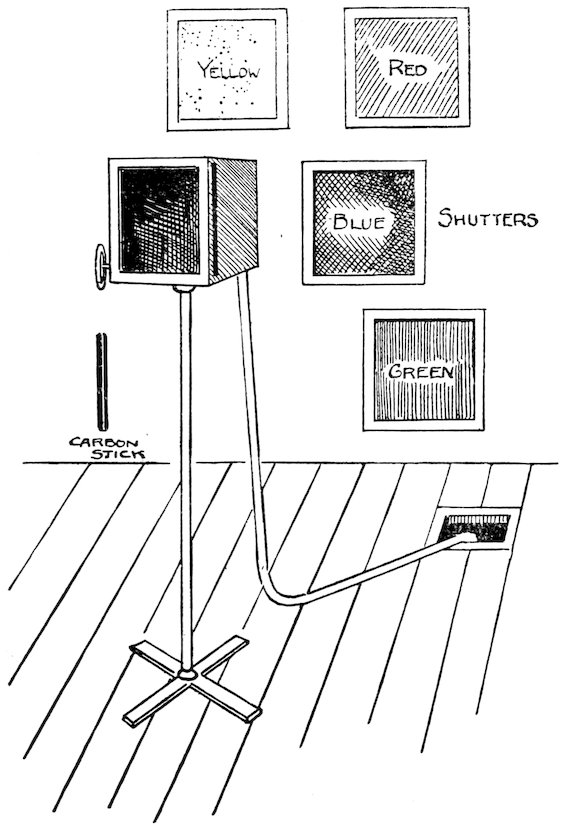

LIMELIGHT BOXES

The colours are obtained by means of Sheets of Gelatine.

64For instance, who has not seen at an amateur production of a play a man coming in from a long country walk—according to the play—wearing boots that had obviously just been cleaned? Or a man walking in from a snowstorm in an overcoat that was perfectly dry? It is the amateur’s inattention to little details of that kind that makes an audience smile indulgently at the stage picture. They say to themselves: ‘After all, they are only amateurs and we must make allowances.’ But there should be no need for such indulgence. A company of amateurs may not be able to succeed in playing a drama with all the skill of professionals, but there is no reason why their stage management should not be ‘clean’ and smart, because, after all, when once you have the knowledge, the production of stage effects is merely a matter of common sense.

The man walking in from a snowstorm should have a little common salt laid on the shoulders of his overcoat just before he enters, and his boots should be ‘made up’ muddy. When he removes his overcoat the ‘snow’ falls away and apparently melts—which, of course, is just what real snow does when a little is brought into a warm room.

The windows of a stage are usually the amateur’s bugbear—or rather one of his many bugbears. I have known an amateur to open a window of a house in a busy London street—according to the stage directions of the play—and, save for the fact that the audience has seen the window opened, there has been no attempt to deceive their sense of hearing; whereas, everyone should know that if you open a window of a house in a busy London street you naturally hear the sound of traffic.

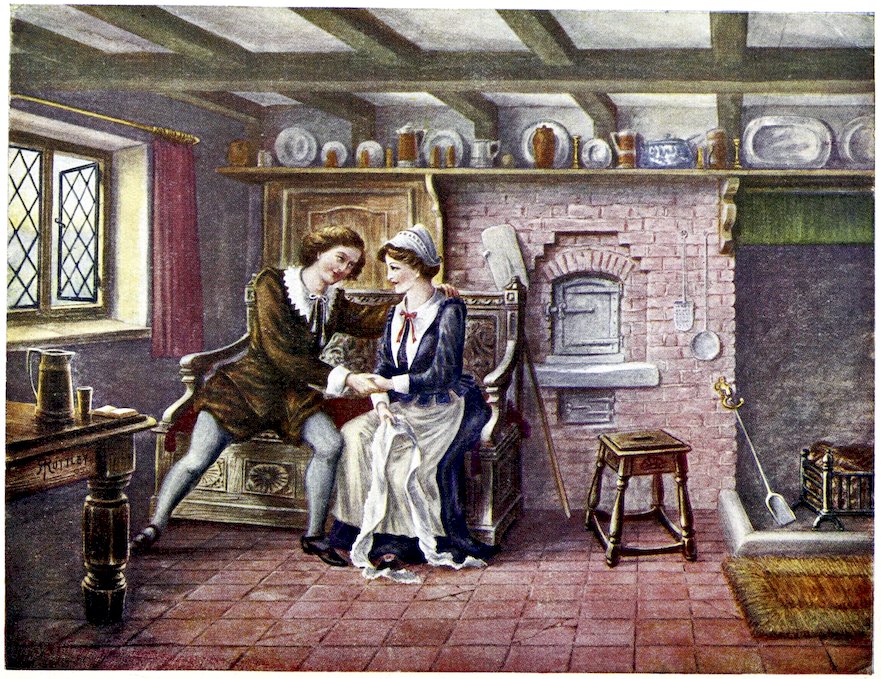

Interior of Ann Hathaway’s Cottage, Stratford-on-Avon.

65Thanks to motor cars this sound of traffic is easily produced on the stage. Two or three motor horns will produce some of the sounds with which people are familiar, but to get the right effect the men using the horns must retire from the window; indeed, one of the horns should be some distance from it in the first place. The only way to get this effect of distance is to stand in the auditorium and have the horns sounded from different places behind the scenes.

The sound of horses trotting up to the imaginary road outside the imaginary house of stage-land is easily produced. The man whose business it is to produce this sound has a couple of wooden blocks, each fitted with a short band of webbing, into which he slips his hands. The blocks are knocked on a board placed on the floor of the stage, and when the horses are supposed to be very near the scene the board is discarded and the wooden blocks are knocked on a slab of slate or marble.

Some men prefer to use cocoanut shells instead of the blocks of wood; the shells, which must be cut or ground flat, give a better ring to the sound. The illustration will show how the blocks or shells are handled.

A thunder storm is imitated by the sounds of wind, rain and thunder combined. The thunder is 66produced from a sheet iron hung from the flies. At the bottom of it there is a handle which the thunder-maker grasps. He shakes the sheet as well as he can, and a sound of booming thunder is heard in the auditorium.

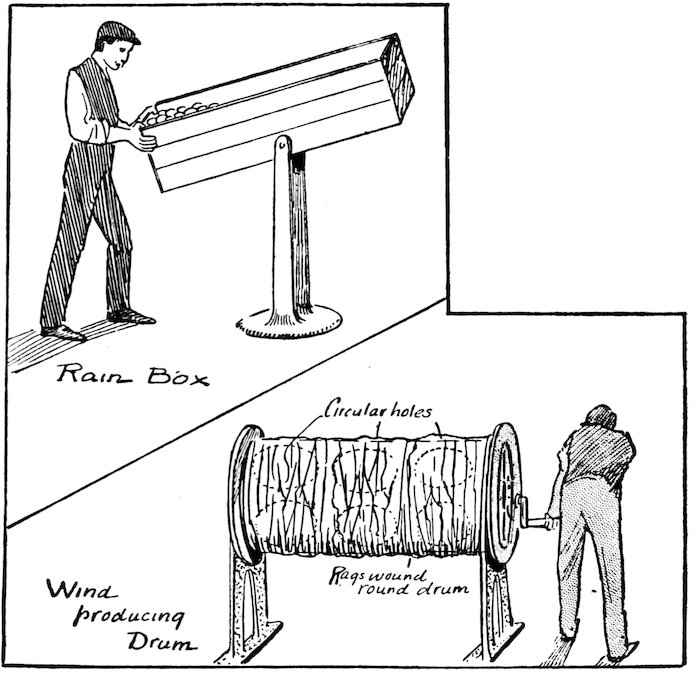

The sound of rain is produced by means of a rain box, fashioned in the following way. Two uprights are fixed on a common base and a large oblong box is fixed between them by means of a couple of pivots in its sides. This box is filled with small stones and the rain-producer stands at one end of the box and moves it up and down, thus 68tilting the stones to and fro in the box. Strange as it will appear to anyone not in the secret, this moving of small stones in a box produces the sound of heavy rain to those sitting in the auditorium. Of course, if rain is to be seen on the stage it may be the real thing—so far as the water is concerned—but it is seldom needed, and then only for a few seconds; in any case, a play that needs such an elaborate effect will probably not be looked upon with favour by any company of amateur players.

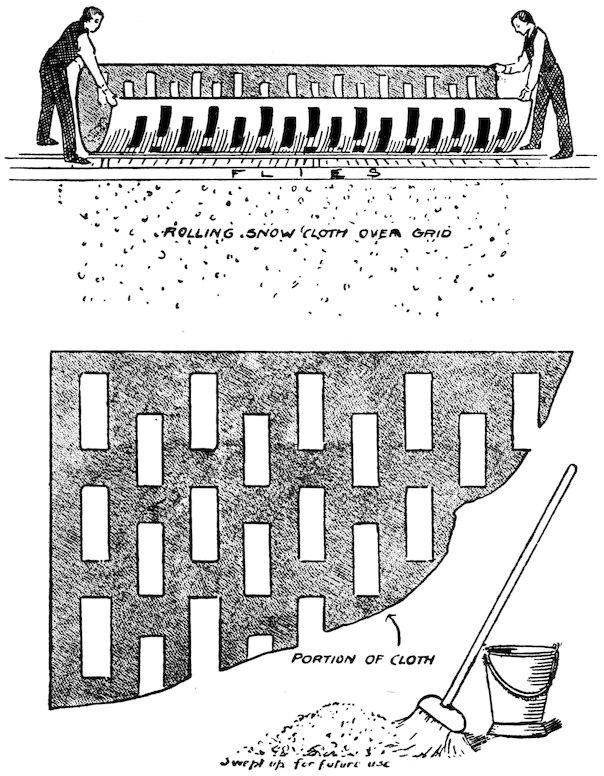

The ‘snow’ that falls on a stage is white paper; if a snow scene is required the blocks of snow may be painted canvas or may be blocks of rock salt.

The snow that is to fall in a pretty snowstorm effect is gathered up in a large cloth with slits in it. This cloth is held in the flies by two men, who move it, in a rocking motion, backwards and forwards, so the paper is caused to fall through the slits in the cloth to the stage below.

That is one method. Another way is to have the ‘snow’ gathered up in a long frame of wire netting—something like an inverted ‘pea net’—and this is fixed in the flies and rocked gently backwards and forwards. With each forward movement some of the paper escapes and the effect of falling snow is produced.

70Snow is mostly wanted for melodramas and pantomimes, and as the runs of these pieces are always considerable the snow is used over and over again. It is usually swept up with a broom and carried upstairs again in pails, but if this plan is not practicable—owing to the changing of a scene,—the snow is gathered up by an army of men with fans. They bend down close to the stage and fan the paper away into a corner. Which ever arrangement is used the amateur stage manager would do well to remember that if the audience are allowed to see a few pieces of the stage snow lying about the stage after the snow storm the illusion is spoiled. I have frequently seen this bad, careless mistake made at good theatres.

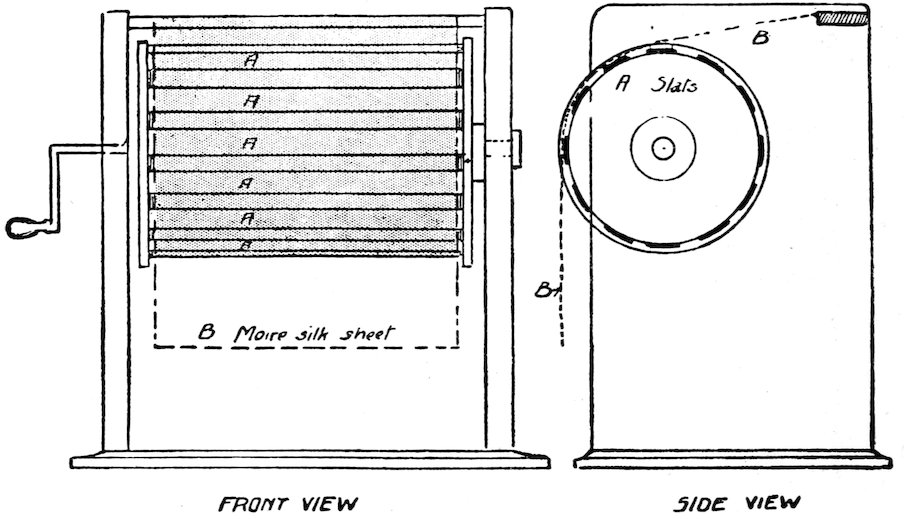

NEWEST WIND MACHINE

Stage wind is produced by means of a large drum or wheel made of slats of wood, with about three inches of space between the slats. This drum is fastened to two uprights and has a large handle 71attached to the centre, so that it can be turned round and round very easily. Above the drum is fixed a stout rod, from which hangs a large piece of moiré silk. This silk hangs over the drum, and when the drum is turned the sound made by the slats of wood touching the silk produces the sound of wind. The illustrations show how the appliance can be made.

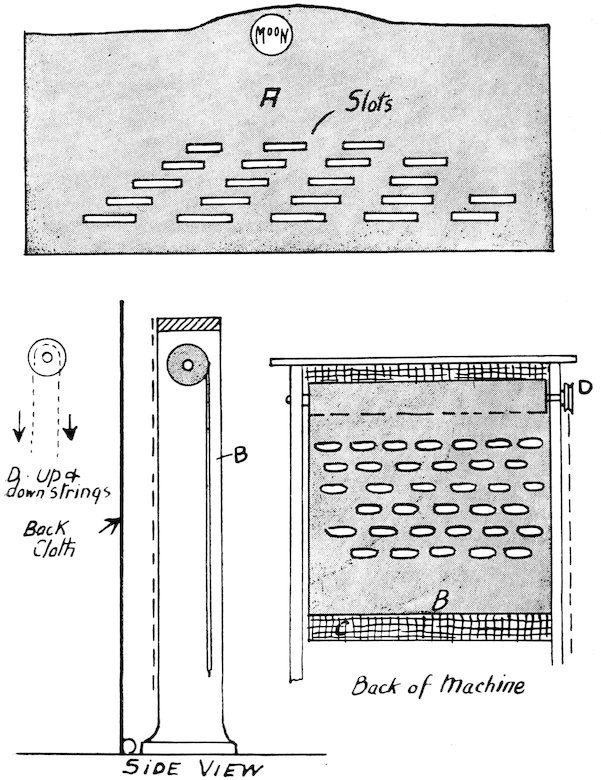

The effect of rippling waves is produced by means of a specially prepared back cloth. This has a number of slits cut in it (see illustration). Behind the back cloth is a machine consisting of two uprights, with a roller-blind attachment at the top, but in place of the blind there is a large sheet of American cloth perforated in the way shown in the illustration. Between this American cloth and the back cloth on the stage is a sheet of prepared gauze. This is necessary, because the strong light which is used to produce the effect of rippling waves must be diffused. The light is that of a strong ‘lime’ placed at the back of the American cloth. Now if the American cloth is pulled up and down by means of the roller on the upright, the effect of rippling waves is produced when one looks at the back cloth ‘from the front.’

The continued success of motion pictures as an entertainment has made it necessary that some of the time-honoured methods of producing stage effects, should be replaced with instruments more adaptable to the limited space of cinematograph theatres. There is no room for instance for a thunder sheet in the operator’s box, or beside the pianist. Incidentally the legitimate stage is also the gainer.

‘RIPPLING WAVES’

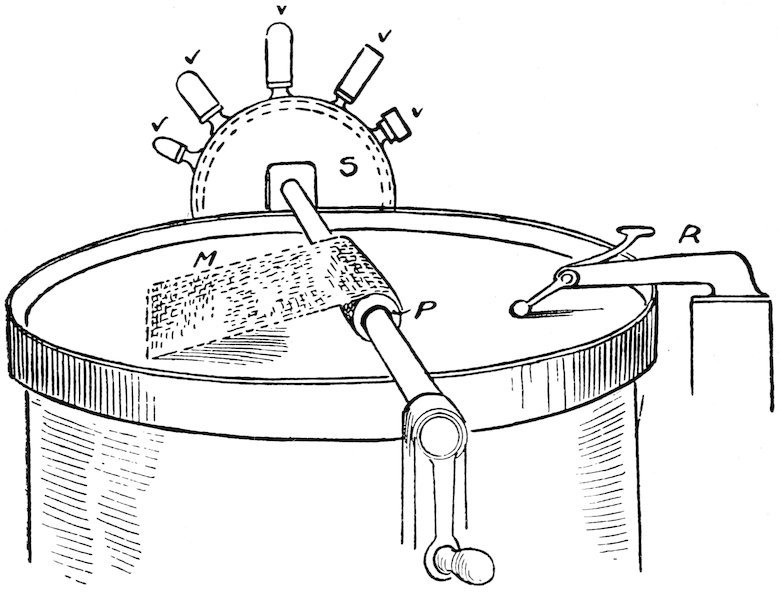

73The following devices here illustrated are the invention of Mr A. H. Moorhouse of Stalybridge.

Fig. 3.

In the first, Figs. 1 and 2, we have an instrument for imitating the trotting horses which can be tuned to any speed or strength. A number of cups are used. ‘A’ one fitting over the other and connected by a spring ‘B.’ The top cup has cuts round the edge to let the sound out. By turning the handle which has the tappets C1 and C2 mounted on its shaft, the top cup is thrown off the other (see Fig. 2) until the tappet C clears when it (the cup) returns making the necessary sound. Now each tappet can be set on the shaft at a different angle, so that the cups open and shut one after the other, thus producing a continuous trotting effect. In order to obtain distance effects the inventor has provided a foot lever by pressing which the platform of the lower cups is thrown out of the vertical, thus the 75tappet only partially strikes the top cup and the sound is consequently much fainter, but as the lever is gradually released the trotting increases in intensity. By having a suspended rod of sleigh-bells, with spring projections for the tappets to strike, effects of moving vehicles can be obtained.

The second drawing (Fig. 3) shows a drum fitted up for producing a variety of sound effects. ‘M’ is a kind of apron of woven wire, which is wound on a drum ‘P’ by means of the handle shown. When the drum is struck the skin on returning strikes the mat with a sharp crack or bang, a sound resembling the firing of heavy artillery. By winding up the mat on its roller the sound can be increased or decreased as desired. On another part of the drum ‘R’ is an instrument for producing the effect of a motor car travelling at various speeds. This can be attached to clock-work mechanism instead of using the handle or lever.

The handle can also be used for working the valve S (compressed air is admitted to the casings and can be made to operate on the various instrument V for producing imitations of wind, whistles, sirens, horns, or any sound producer) that is attached to the valve.