*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 76341 ***

Transcriber’s Note: “ro” was changed to “to” ... desire to run ...

COLOMBINE

A FANTASY

AND OTHER VERSES

LONDON

BENN AND CRONIN, LTD.

CRAVEN HOUSE, KINGSWAY, W.C.

1911

Copyright: Entered at Stationers’ Hall, December 1911.

Acting Rights strictly Reserved.

COLOMBINE.

COLOMBINE

A FANTASY

BY REGINALD ARKELL

WITH SOME DRAWINGS

BY FREDERICK CARTER.

“Colombine” was first performed at Clavier Hall, Hanover

Square, W., on Thursday, 7th December 1911, with

the following cast:

| Dan’l (an old man) |

Mr. B. Butler. |

| Nathan’l (a boy) |

Mr. A. E. Filmer. |

|

(By permission of Miss Lillah McCarthy) |

| Harlequin |

Mr. Reginald Bach. |

| Pierrot |

Mr. Mark Hannam. |

|

(By permission of Miss Lillah McCarthy) |

| Colombine |

Miss Ethel Evans. |

| The play was produced by Mr. A. E. Filmer. |

SCENE

A Roman Camp on the summit of Cissbury Beacon

in the South Downs. A fairy ring occupies the

foreground. All round are beech trees. The

time is evening.

PROLOGUE

There are circles of green upon Cissbury Hill,

Where the Pharisees dance—so they say;

Revelling merrily round it until

The dawn over Ditchling is gray.

And travellers lost upon Cissbury Hill—

(Pixy-led folk who stray)

Seated on toad-stools, with fairy folk sup,

But here, in Haymarket, the roadway is up.

There are circles of beech upon Cissbury Hill,

Where the leaves of a lifetime decay;

Hiding the memories, lingering still,

Of Rome’s indisputable sway.

And under the beech-leaves of Cissbury Hill,

Throbs the heart of the downland alway.

While dreaming of chieftains and warriors in woad,

You’re lighting your pipe in the Charing Cross Road.

COLOMBINE

An old man and a boy are seen talking; both are labourers.

The old man, who is seated, speaks:

Dan’l. There’s little use in stopping here much longer.

Nathan’l. Not as I can see.

Dan’l. Like my old eyes, the sun don’t grow no stronger.

Nathan’l. And I wants my tea.

Dan’l. Which means ’tis time to go, I reckons.

Nathan’l. That’s a proposition as I seconds.

Dan’l. Come on then, let’s be moving. Tip us yer daddle.

Nathan’l. All of a sudden you be in a mortal caddle.

I wants to hear the finish of that yarn

As you was spinning down at Tranter’s Barn.

A peck of troubles it was all about.

I wants to know how everything turned out.

Dan’l. You wants your tea, that’s what you wants, my son.

Nathan’l. There’s time enough for tea when you be done.

Dan’l. Well, though ’tis little enough I read,

I sid in a story-book years ago,

(Though mind, Nathan’l, there beant no need

To be letting on as I told ee so)

That all the troubles as worrits a man

Was locked in a box when the world began.

And there no doubt they’d ha’ bid till now,

If the dummel soul as had got the key,

Hadn’t got mixed up with a maid somehow

And gone and handed it over to she.

And what do ee fancy the maiden did?

Darn me, Nathan’l, ur lifted the lid.

And all they troubles come trooping out,

Like hens from a chicken-run might have done.

For the maiden fancied without a doubt,

They’d go back in the evening like, one by one.

But time’s got to settle a few more clocks,

Afore they troubles goes back to their box.

Straight, Nathan’l, ’tis near enough

To make a methody parson swear.

And every time as I reads such stuff,

I goes so red as yon moon up there.

To think of the trouble ur brought on we—

I reckon I owes my old gal to she.

Nathan’l. Is it true, do ee think, Dan’l?

Dan’l. Mebbe, mebbe not, Nathan’l.

Nathan’l. Do ee think, Dan’l—she let out the lot?

Dan’l. Mebbe, Nathan’l, mebbe not.

Nathan’l. Sounds like a fairy story to me.

Dan’l. Mebbe, Nathan’l, mebbe, mebbe.

Nathan’l. Do ee believe in fairies, Dan’l?

Dan’l. Can’t be sure as I do, Nathan’l.

Nathan’l. Well, I don’t anyway, and that’s a fact.

Dan’l. Lawks-a-mussey, Nathan’l, be I dreaming or be I cracked?

Nathan’l. My goodness, Dan’l, I do believe as she’s a fairy....

Dan’l. Here, come into the shadow of these trees,

And give that clacking tongue of yourn a rest.

Nathan’l. Oh, this be more wonderful than all the things I ever guessed.

Dan’l. And it means summat that you may depend.

Nathan’l. See, where she walks, the grass don’t even bend

Beneath her feet. She be a fairy, Dan’l.

Dan’l. I wish you’d hold your clacking tongue, Nathan’l.

[Colombine, hearing a noise, pauses to listen.

Colombine. Who’s there? The daylight fades. I cannot see.

Dan’l. So please you, Miss, ’tis we.

Colombine. Good evening, Sirs.

Dan’l. Our best respects to ee.

A goodish evening to be sure, but getting dark and cold.

Time gals like you was safe abed, if I might make so bold.

Colombine. Old man, the night has but begun.

Colombine. The moon has scarcely risen yet.

Colombine. The sun his wandering footsteps stays to greet the crescent moon.

The nightjar and the nightingale will both be singing soon.

Dan’l. Us don’t set much store by nightingales in

these parts, and as for nightjars! Oh lor, us shoots they.

Give I a linnet now,

A-sitting on a bough;

As sings his message to the sun,

And goes to sleep when day be done,

Respectable like!

Nathan’l. [Coming forward.]

Queer things,

These here rings

You sees in the grass

When you pass.

They say ’tis where Pharisees dances at night!

Be that right?

Colombine. Quite right; yet once the circle that you see,

Saw war and tumult.

Dan’l. Lawks-a-mussey me!

Colombine. The Roman legions camped on yonder brow,

And built the road you stand on.

Colombine. The sun would sink out yonder in the west,

And shine upon their helmets.

Colombine. The very spot where Julius Caesar sat,

Lies just behind those beeches.

Colombine. In yonder barrow treasures rare lie hid.

Dig deep to find them.

Nathan’l. But when did all this

Happen, Miss?

How many years ago,

I’d like to know?

Colombine. Roughly two thousand, on this very spot.

Dan’l. Lor! What a memory you must have got.

Colombine. [To Nathan’l.] But tell me please;

Beneath these trees,

What travellers come, and whither bound?

Do still these ancient heights resound

With martial music and the tramp of men?

Nathan’l. Us gets a hurdy-gurdy now and then,

And once a clown on stilts went through the wood;

And oh! he could catch pennies, that he could.

Colombine. But in what fashion do you pass your days?

Nathan’l. I kill the time in various sorts of ways.

Scaring the rooks as settles on the corn;

Helping the shepherd when the lambs be born.

Talking to Dan’l about these here rings,

And wondering about a power of things.

As don’t concern nobody, I suppose.

But then, you must do summat, goodness knows.

Colombine. Of course. ’Tis lonely here without a doubt.

What are the things you’re wondering about

To-day?

Nathan’l. Such things as surely never was.

Such things as surely no one ever does.

And yet, of nothing, for they moves so fast,

You finds as you’ve forgotten them at last.

Just like a dream they passes and be gone.

Just like a dream they passes....

Nathan’l. Just like a dream, for though I thinks a lot,

Before they’re rightly thought they’re clean forgot.

Though somehow, now I sits and talks to you,

I keeps remembering things I never knew.

Just like as though somebody slammed a door,

When you was going where you’d been before;

Leaving you standing on the further side,

Wondering at what was happening inside.

Whether the folk you knew was there or not;

Whether you really knew, and had forgot;

Whether you’d been there once when you was small,

Or whether you was never there at all.

’Tis plaguey awkerd, wondering, that it be.

And now I must be off, I wants my tea.

[Exit.

Colombine. Good-bye. And think sometimes of me.

[Rousing herself from the brown study into

which this revelation has thrown her, and

addressing Dan’l.

Colombine. Are you fond of a fight?

Dan’l. It all depends. Why?

Colombine. There’s going to be a fight.

Colombine. Very soon.

By the light of the moon.

On the very stroke of nine.

All for love of Colombine.

Dan’l. Shall I fetch a policeman?

Colombine. A policeman! Dear me, no.

Dan’l. Who’s going to fight.

Colombine. Don’t you know?

Harlequin and Pierrot.

Dan’l. Never heard of they.

Colombine. Won’t it be fun?

Dan’l. Good fun

For the one as gets killed.

Colombine. But they won’t kill each other. They

never do. They’re most dependable.

Dan’l. Have um fought before?

Colombine. Of course. Hundreds of times.

Dan’l. Silly young chaps.

Colombine. They’re not silly. They’re fighting for

me. Don’t you understand?

Dan’l. I fought about a girl once. But only once.

It was a long time ago.

Colombine. You’re not romantic. Romance would

die if it wasn’t for fighting. Romance is fighting.

Dan’l. Then I’ve had quite enough romance to

please me.

Colombine. All properly constituted love affairs

should include a fight. Love without fighting is

insipid.

Dan’l. You don’t have to do the fighting. Which

of ’em loves you the most?

Colombine. Why, Pierrot, of course.

Dan’l. Then why don’t you marry him?

Colombine. And disappoint Harlequin? I couldn’t

do that.

Dan’l. When are you going to decide?

Colombine. I don’t know. [On her fingers.] This

year, next year, some time, never. To-night perhaps.

Dan’l. One day they’ll get tired of fighting. What

then?

Colombine. Never!

Dan’l. You’re sure of that?

Colombine. Oh, yes. Quite sure.

Dan’l. One of them may get killed.

Colombine. They wouldn’t be so careless.

Dan’l. What should you do if one of ’em got killed

by accident?

Colombine. I should be very angry. But you’re

very horrid to suggest such things. Why don’t you

go away?

Dan’l. Good-bye.

Colombine. No, stay.

Dan’l. Well, I’m fond of a fight, I must say.

Colombine. Hush! They are coming. Quick, behind

this tree.

Dan’l. Anywhere in the background’s good enough

for me.

Colombine. A fight, a fight! And all for love

of me.

[The orchestra plays quietly the Soldiers’ Chorus

and snatches of other martial refrains.

The two watchers betray tense excitement.

Harlequin and Pierrot enter arm in

arm. Any differences they may have had

are evidently settled. Colombine looks

on in astonishment.

Harlequin. Mind you, as girls go, Colombine’s one

of the best.

Pierrot. Ah yes.

Harlequin. But nothing to fight about.

Pierrot. [Without conviction.] No.

Harlequin. And fighting’s going out of fashion.

There’s no doubt about that.

Pierrot. Yes.

Harlequin. The whole trend of modern thought

is opposed to it.

Pierrot. Yes.

Harlequin. None of the best people do it.

Pierrot. I suppose not.

Harlequin. And one must be in the movement.

Pierrot. Of course.

Harlequin. Arbitration’s the thing nowadays.

Pierrot. What’s that?

Harlequin. Why, you each talk until you’re out

of breath, and the one with most breath wins.

Pierrot. [Taking a deep breath.] That seems a

good idea.

Harlequin. It is.

Pierrot. But what will Colombine say if we don’t

fight? She loves to watch us fight.

Harlequin. My dear chap, we must be firm.

Adopt your point of view, and stick to it in the face

of all opposition.

Colombine. [Advancing.] Aren’t you going to fight?

Pierrot. [Kindly.] Not to-night.

Harlequin. Well, we’ve got

Other fish to fry,

That’s why.

Harlequin. Now, my dear girl, do listen to reason.

You will admit, I suppose, that the most elementary

point about a duel is to spit your opponent through

the gizzard.

Colombine. Yes.

Harlequin. Well, I haven’t got a gizzard, and

what’s the use of trying to spit a man’s gizzard, if he

hasn’t got a gizzard to spit? You must be reasonable.

Colombine. How do you know you haven’t got a

gizzard?

Harlequin. We don’t know for certain, we assume.

Pierrot. You’ve only to look at him to see there

isn’t room.

Colombine. But why the gizzard? What does it

matter where you spit him so long as you do spit him?

Harlequin. For heaven’s sake, my dear girl, don’t

preach such revolutionary doctrines. There is a certain

etiquette to be observed, even in a battle.

Colombine. [After a pause.] But it’s quite simple.

You spit Pierrot. He’s got a gizzard, I suppose.

Harlequin. Now, listen. Pierrot consulted a

phrenologist....

Pierrot. Soothsayer!

Harlequin. Sorry—soothsayer, who said he was

born to be hung....

Pierrot. Hanged!

Harlequin. Hanged, and so of course, he doesn’t

want to run the risk of disappointing him.

Colombine. Very considerate, I’m sure.

I think you’re absolutely horrid, there.

[Cries.

Harlequin. [To Pierrot.] Don’t waver, both together.

Harlequin and Pierrot. We don’t care

Tuppence what you think or say,

We talked the matter over, here to-day;

And arbitration is the only way.

Colombine. You’re frightened.

Harlequin. Don’t be silly. Frightened! Me!

Colombine. Well, who’s your arbitrator going to be?

Harlequin. [Taken aback.] Why yes, we must have someone, I suppose.

But who’s to do it?

Pierrot. Goodness only knows!

There’s not a single person within call.

Colombine. [Clapping her hands.] Hurrah! You’ll have to fight, then, after all.

[There is a pause, during which Pierrot and

Harlequin look at each other in dismay.

Colombine on the other hand claps her

hands and pirouettes round the stage. Then

Harlequin sees Dan’l and drags him forward

at the same time speaking in asides.

Harlequin. What’s your name?

Dan’l. Much the same

As it’s always bin,

Week out, week in,

This seventy year and more.

Harlequin. Good! We want you to arbitrate.

You’re the very man.

Dan’l. Lawks-a-mussey. I’ll do it if I can.

Harlequin. There’s much gold.

Wealth untold!

If you only do

As I tell you to.

Harlequin. Until to-day, Pierrot and I have been

in the habit of engaging in mortal combat for the hand

of Colombine. Owing to the fact that up to the present

neither has had the decency to get killed, and as a

result of the wave of anti-militarism that has swept over

the country, we have decided to fall back on arbitration.

And you are the arbitrator. You understand?

Harlequin. Then you’re very thick.

Dan’l. You speaks too quick

And the way you keeps hopping about makes me fair mazed.

Harlequin. Now, listen. One of us is to marry

Colombine, and you’ve to decide which it’s to be.

Do you see?

Harlequin. But it’s quite simple.

Dan’l. Maybe. But how do I know which it’s to be?

Harlequin. I’ll let you into a secret. It’s me!

Dan’l. Oh! And if I goes and sez ’tis you,

What’s yon chap in the white trousers going to do?

Harlequin. Never mind him. He’s a fool.

Dan’l. It seems it don’t much matter what I say;

I’m bound to upset one of ye either way.

Oh! very well.

Harlequin. Colombine! Pierrot! Gather round.

[They sit in a semicircle; Colombine and

Dan’l in the centre.

Dan’l. I shall catch my death of cold, sitting on

this damp ground.

[There is silence, each waiting for the other to speak.

Colombine. You don’t seem very anxious, either

of you.

Dan’l. Who goes first?

Harlequin. If I don’t say something, and quickly, I shall burst.

Dan’l. Then you’d best get started. [Aside.] How long will it take?

Harlequin. Until it’s ended.

Dan’l. Cut it short for goodness’ sake.

Harlequin. Colombine! Let me take you away

from these lonely hills. Into the heart of the world

where lies the Land of Yesterday. There are stored

all the happy hours that you have known. You shall

live them all over again, Colombine—every one. I

will lead you by secret paths, through the dim woods

of yesternight until we stand together in the sunlight

of the days that have been. Walking backward

through the years, we will collect those dear lost

delights, of which only the memory remains. From

all that has gone before, it shall be yours to pick and

choose, and no To-morrow shall throw its ominous

shade before. The past shall deliver up its treasures

to your hand; regrets shall be ended, and happiness

shall be sure. Will you come, Colombine?

Colombine. No, Harlequin. The road to your

Land of Yesterday is longer than you know, and there

is no going back. Let us still take from the past our

memories and our dreams, but do not ask for more,

lest even these be denied.

Harlequin. As you will. Then it is to the future

that we must turn. Colombine, far from here, set in a

desert of hot sand, is a crystal, so large, that all the

giants of Africa could not stir it the thickness of a hair.

Peering into its depths, you may read your future to

the end of time. A day, a week, a year, shall be no

barrier to the vision of the mind. You may read all

the riddles of the universe, and there will remain

nothing that you do not know. You shall see your

face as it will be when twice twenty harvest moons

have waned, and fifty summer suns have set. And

I, alone, can point you the way. Will you come,

Colombine?

Colombine. You promise much, Harlequin. It may

well be that in some spot remote from the haunts of

men, the Mirror of Fate yet lies hid. And you may

find it. Who knows! But this, at least, is certain;

the path will be difficult and the journey long. Would

you not tire by the way, Harlequin? I think you

would. [Pause.] And, it is not in distant deserts I

would seek. In the woods of home, hearts may thrill

to the eloquent silences of the night. [Harlequin

rises.] All the secrets of the world might be ours, did

we but care to learn the simple language of the

nightingale. Across the moonlight, the shadows of

the branches trace unforgettable things. Great secrets

tremble on the lips of the leaves, and mortals grope

vainly in the daylight for things seen most plainly in

the dark.

Dan’l. [Coughing to draw attention to himself.]

I’ve allus noticed, in whatever parts I med ha’ bin,

A maid in love have allus got a fairish yarn to spin.

And in whatever parts I’ve bin, I’ve allus noticed too,

The foolish lads do take it all for gospel, that um do.

But though I’ve kept good notice in whatever parts I was,

I’ve never heard a maid to spin a yarn like this un does.

Ur be a marvel, that ur be; I hope as ur won’t try

When ur’s tired of you two fellows here, to spin no yarns to I;

For fools be mostly biggest fools when um be old and grey.

And if I went along o’ she, what ud my missus say.

Next man?

Colombine. Come, Pierrot!

Pierrot. [With an effort.] Colombine!

Colombine. Yes, Pierrot.

Harlequin. Go on!

Dan’l. Let’s hear what you’ve got to say, young

fellow.

Pierrot. There is nothing to say.

Colombine. Nothing to say!

Pierrot. Save that I love you, Colombine.

Colombine. And is that so small a thing, Pierrot?

Pierrot. But I have nothing to offer you, nothing.

Colombine. [Softly.] Save yourself.

Harlequin. I have always said that Pierrot was

master of sounding silences. The sweetest singer of

unsung songs, his eloquent nothings go shrieking

through the void. He scorns to desecrate the virgin

purity of his foolscap with the written word. What

love is that which dare not tell its love? Come,

Colombine.

Colombine. See, Harlequin, here is a beech nut.

You shake it, yet there is no sound. Is it full? Is it

empty?

Harlequin. Who can say?

Dan’l. Likewise, young Nathan’l he picks up a

match-box last week, and throws it away because there

was no sound when he rattles en [To Harlequin.]

And what do you think?

Harlequin. I couldn’t say.

Dan’l. It was so full all the time as not to rattle

at all.

Harlequin. [Scornfully.] Matches! ye gods! Let’s talk of cucumbers,

Or shame the glory of this summer night

With tales of warming-pans.

Has no one here a button-hook,

With which to probe the vast unsounded deeps

[To Dan’l.] Of thy poor addled brain.

It yet may be,

In some uncharted corner of the void

That passes for thy mind,

We find a collar-stud.

Farewell!

[Exit.

Dan’l. Well, he won’t come back again, that I will be bound,

And as I be catching my death of cold, sitting on this damp ground,

I’d best be moving. [Rises.] Ugh! Good-night to ee.

Colombine. [Aside to Dan’l.] And, Mr. Arbitrator, if you see

Your friend Nathan’l, say that Pierrot

Owes more to him than he will ever know.

[Exit Dan’l.

Colombine. They have gone!

Colombine. And the night draws on.

Colombine. You are sad. Why are you sad, Pierrot?

Colombine. And you are cold. Is it the night air?

Pierrot. The wind-swept wold

Is a street of gold,

So my lady be walking there.

Colombine. Yet you are sad. See, they have gone

and will not come again.

Pierrot. So love may vanish too,

And of his chain no link remain

To tell the way he flew.

Colombine. Love, as the skylark, soars into that

Heaven where’t fain would be.

Pierrot. And singing still, returns. Time was

when you, with Harlequin, would revel till the cold

grey dawn came in.

Colombine. Light loves sometime were pleasant,

but to-night the face of love seems changed. No

more will stray this wandering heart of mine.

Pierrot. Are you not sorry, Colombine?

Colombine. Sorry for what, Pierrot?

Pierrot. For loss of Harlequin.

Colombine. Harlequin is very clever but he talks

of what he does not know, and promises what is not

his to give. Cleverness is not everything, Pierrot.

The mind is like a garden full of flowers, but

The heart is a little house,

With windows facing southerly;

By which a pathway winds.

And there, behind the blinds,

We sit and wait,

Watching, waiting for what?

We know not.

The garden is a pleasant place in summer, but

when it is winter, we seek the fireside of the little

house.

Pierrot. Yet you are fond of gardens and pretty

flowers, Colombine?

Colombine. What flowers grow

In your garden, Pierrot?

Pierrot. My garden is full of the flowers,

My mother planted for me;

Curious, old-world flowers,

Thyme, lavender, rosemary.

Planted in days gone by.

And, though no gardener I,

As the shadows fall, I tend them all;

Watering, pruning there.

Am I happy in my lot?

I know not.

Colombine. And there is the little house, Pierrot.

Pierrot. Ah, yes there is the little house.

Do you remember when

You peeped through the pane, and then

Went on your way again?

Out of my sight, although,

I beckoned you as you passed,

And sat at my window mournfully.

But you came again at last.

And, seeing you come, I said;

“The flowers in my garden are dead,

So will she have no more of me.”

Colombine. I am knocking at the door, Pierrot.

Knocking and waiting there,

For the sound of a step on the stair.

Will you open to me, Pierrot?

[Pierrot’s answer may be taken in the

affirmative. As they sit together, it

grows dark.

Pierrot. [Rising.] Come dear, and let us go,

Together, hand in hand,

Into that sun-lit land,

Where life and love are things inseparable.

Where, beneath cloudless skies,

The happy are the wise,

And none reprove the glory of a love they may not understand.

[Exit together.

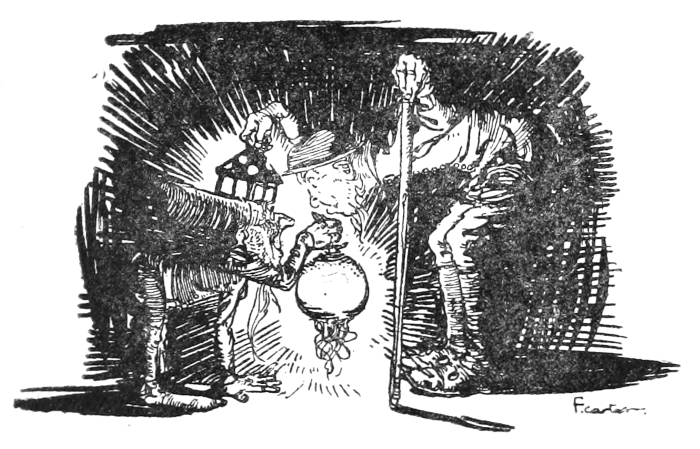

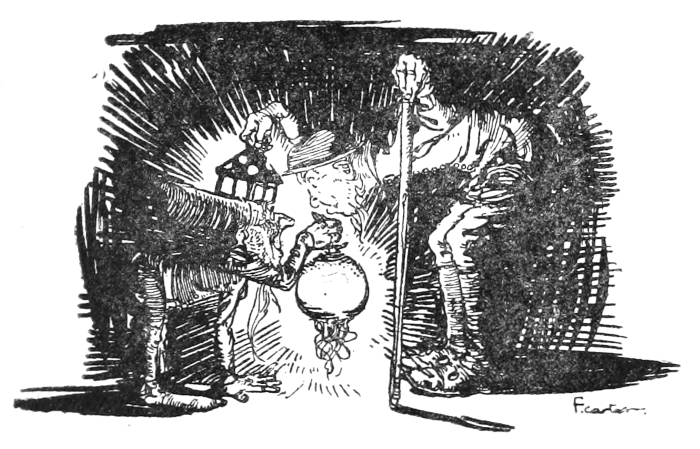

[It becomes quite dark: Dan’l and an Old

Man pass slowly across the stage, carrying

lanterns, and peering cautiously into the

blackness of the night.

The Old Man. You was dreaming, Dan’l. That’s

about the size of it.

Dan’l. And I tells ee I wur as wide awake as you

be. Us had been sitting over-long by the clump,

and all of a sudden I looks up and sees a fairy.

“Lawks-a-mussey, Nathan’l,” I sez, “be I dreaming

or be I cracked?”

[They pass off, and the curtain falls.

FINIS

OTHER VERSES

THE MARIONETTE

M an is merely a marionette

On invisible wires suspended.

And it’s just as well he shouldn’t forget

That Fate the showman is in the wings,

Working the business and pulling the strings

Till his turn is over and ended.

Man is merely a figure on strings,

By the glare of the footlights blinded.

And the wonderful way he dances and sings

Is not unlikely to fill his mind

With a great contempt for the Power behind,

Till suddenly he’s reminded.

Man is the cream of an idle jest,

A smile on the face of sorrow.

A sad peculiar figure at best;

Willing to sacrifice every day,

Breaking his heart in the hope of play

On a problematical morrow.

A LETTER FROM HOME

I’ve a letter from home to-day;

A letter from home to say

That they’re cutting the trees in the Priory Wood,

That lambing is over and crops are good.

Quite the usual thing, be it understood,

Is my letter from home, to-day.

I’ve a letter from home, to-day;

A letter from far away,

Bidding me ever to bear in mind

The dear old friends I have left behind.

But I’m not of the quickly forgetting kind,

Dear letter from home, to-day!

In my letter from home, to-day;

Is a postscript, just to say

“No doubt you’ll be very much grieved to hear

That the girl who stayed at the Grange last year,

Is dead, and was yesterday buried here.”

And the world has ended, to-day.

THE EXPLANATION

How do I know I love you?

Why, because

When you’re away, d’ye see,

I kind o’ wanders lonesome like

An’ frets,

’Cause you’re not there with me.

An’ when I meet you by the stile

At night,

And not a soul to see,

I scarce durst speak to you because

You’re you, an’ I’m just me.

MEMORANDA

In your Book of Memory,

Set aside no page for me.

Do not write our friendship there,

But, if you’ve the time to spare,

Scribble just this hurried line:

“He was once a friend of mine.”

Blot it very carefully,

Turn the page that none may see.

Life goes singing down the way

Different ballads every day.

Other pages open fair,

Set new tales of friendship there.

And the day will come maybe,

When that hurried line of me;

Seen by chance a moment’s space,

Will recall a vanished face,

And a memory sweeter than

Many written pages can.

LOVE, LAUGHTER, AND AFTER

The ruinous cottage, the broken latch;

The cold stone floor and the dripping thatch.

The ripe red lips of the girl who stands

Holding her lover’s hands.

The gay Casino, the fancy ball;

The twinkling lights of the crowded hall.

The cool sweet air of the terrace dim,

Love and laughter and—him.

The pitiful pageant that follows soon;

The music hall and the cheap saloon.

The sad procession, the coffee stall.

The river that ends it all.

TH’ COORTIN’

’Tis just about a wik ago,

Or mebbe two, or theresabout,

As I axed Kate why ur an’ Joe

Was seed together waalking out;

Whenas, fur nigh upon a year,

’Twur I as had been coortin’ ur.

“Why, laws-a-mussey, Bill,” ur sez,

“Fur certain sure ye must allow

Us two caan’t alluz spend our days

The same as us be doin’ now.

Ye’d better wed wi’ one ye doan’t

Than waalk wi’ one ye do, as woan’t.”

I cudden zackly understand

What ’twur as she was drivin’ at,

Until I cotched ur by the hand

And took a peep ’erneath ur hat.

Wur what I see surprised I so,

I gi’ed ur kiss, an’ whispered low:

“Ye’d better wed the feller who

Has alluz bin in luv wi’ you.”

And that’s just what ur means to do.

AGREEMENT

Oyez! Oyez! Behold we state

The rules of this our Syndicate.

Let it be granted first of all,

That you are not so young and small

As foolish people would suppose,

From your long hair and shorter clothes.

Item the second, please agree

To just the opposite in me.

For would the wisest man alive

Imagine I was twenty-five?

This done, folk cannot make a fuss,

Or say that we’re preposterous.

For you become, as all may see,

A chaperone in charge of me.

Thirdly, this reservation’s made,

The Syndicate’s too old and staid

To ride (though you’ll object no doubt)

In swinging boat and roundabout.

Fourthly, the world’s a dear old place,

So always keep a smiling face.

It suits you best, and as to that,

So does pink chiffon in your hat.

Lastly, lest envious folk combine

To wreck your Syndicate, and mine,

My autograph is here affixed,

Written in blood and water mixed.

P.S. It may not look like blood to you

But recollect my blood is blue.

THE BURYIN’

The mists be on the river bed,

The roses all be gone;

And here be I, about to die,

Wi’ harvest coming on.

Dear Lord, I’ve trapsed some weary miles,

I’ll be main glad to rest awhiles.

The folk’ll soon be in the fields,

A-getting in the grain.

For most of those, the time I’ve chose

Be awkerd in the main.

Though not so bad, ’tis sure, for they

As be a-working by the day.

September be a better month

For all the carter men;

And when I die don’t signify,

So let I bide till then.

The wagons’ll be standing by,

And there’ll be time to bury I.

A ZONG TO ZING-OH!

When the zun beyond the Beacon be a-zettin’

And everything’s as quiet as can be,

By the gate to varmur’s meddy,

That old gate zo vurm and zteddy,

You be pretty zure uv vindin’ Jim and me.

When the mists along the valley be uprisin’

And the nightingale’s a-zingin’ in the tree;

When the peewits be a-zquawkin’

Uz don’t waste no time a-talkin’

Time’s a vasty zight too short sez Jim an’ me

With the honeyzuckle zcent zo thick as treacle,

And the chestnut blossoms droppin’ onto we;

As us zets zo close together,

Why zometimes I wonders whether

Jim ull zet that close in Paradise to me.

When the clocks down in the village be a-strikin’

And darkness comes a-creepin’ up the lea,

Then, though us be zeldom ready,

Us must leave old varmur’s meddy,

Or the volk ull all be wonderin’ where us be.

SONG

Long ago,

(How long ago I really don’t know;)

A kingfisher lived in a valley of green,

The finest kingfisher that ever was seen—

In that little green valley I know.

Silent and slow

All in a row, buttercups grow.

One day the kingfisher selected his queen,

And the bride wore a costume of purple and green

’Neath the willows that stand in a row.

Heigho!

(As the years go, still the streams flow)

The whole of this summer they haven’t been seen,

And a wood-pecker reigns in that valley serene.

Where they’ve gone to I really don’t know.

PHILOSOPHY

When I was young, in days gone by,

I smoked Wild Woodbines on the sly.

They made me ill, but what of that?

’Twas nothing much to grumble at;

For, don’t you see?—

If I had shirked that pallid brow

I couldn’t smoke Havanas now.

The only girl I ever kissed,

Both found and left an optimist.

She jilted me, but even that

Was nothing much to grumble at;

For, don’t you see?—

I’ve such a cozy little den,

And know a lot of married men.

And now, although I’m getting stout,

And though my hair is falling out,

And people call me old and fat,

There’s nothing much to grumble at;

For, don’t you see?—

Although I am a perfect fright,

I don’t look bad by candle light.

FORFEITS

Y ou fail to catch the trencher spun

And, later, when the game is done,

The lady who collects the fees

Demands a forfeit, if you please.

You find a penny, grimed and black,

And hope that you may get it back.

You sit in speechless misery,

And wonder what your fate will be,

Until, within that giggling ring,

You have to claim the wretched thing;

Then sally forth upon your quest,

To kiss the one you love the best.

You don’t appreciate the fun,

But curb a wild desire

to run;

Then seek a matron staid and stout,

And drag the willing victim out;

Because, of course, it wouldn’t do

To kiss the girl you wanted to.

THE REVIVAL

Take me away, for I will see no more;

It was but yesterday I saw the play before,

The day on which my dear and I were wed—

Your mother, child—your mother who is dead.

Why did you bring me here to see a play

Which she and I saw only yesterday?

A PATRON OF THE ARTS

I knew a lady once I did,

Who lived away at Pontypridd;

She liked my verses very much,

And said I had the lyric touch.

She used to ask me round to lunch,

And say I ought to edit “Punch,”

As Owen S. and Francis B.,

Were amateurs compared to me.

Last week I met her in a batch

Of lunatics at Colney Hatch,

And heard she always spoke of me

As far surpassing Calverley.

CRITICISM

A simple poet on a time,

Resolved to write a simple rhyme.

His verse was pleasing to the ear;

He also made his meaning clear.

The critics glanced at it, and said

Such rubbish they had never read.

A point on which they did agree,

With touching unanimity.

The simple poet took his lay,

And turned it round the other way.

Shuffled the sentences about,

And took a dozen commas out.

The critics took the volume, and

Read, marked—and failed to understand.

Then fell upon their stomachs flat,

This prodigy to marvel at.

TREASON AND PLOT

When I am very, very rich,

And very famous, too,

I’ll take a cab to Regent’s Park,

And walk into the Zoo

With quite a consequential air,

For I shall be the richest there.

And in a lordly way I’ll take

A shilling from my purse,

And buy the biggest rattle-snake

To carry home to Nurse,

And, as she’s very short of breath,

Perhaps ’twill frighten her to death.

THE POPPY AND THE POET

Like poppies in the golden corn,

The poet’s race is run;

Each strives alike to gain the ear;

The poppy from the sun

Borrows more radiance than gold—

A poet’s much the same, I’m told.

But still these differences appear

When everything is said;

The poet’s leaves, I greatly fear,

Are very seldom read.

Poppies but borrow from the sun—

A poet will from anyone.

EL DORADO

He sought it through the golden isles

Of Once Upon a Time.

In fabled fields of Might Have Been

He heard its distant chime.

He saw, mid Dreamland’s mystic glades,

Its turrets from afar;

And found it in the valley, where

The deepest shadows are.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 76341 ***